As a recently excavated site in Pompeii has demonstrated so beautifully, street food is ancient. Both sold on the street and usually consumed on the street, it is food that is inexpensive, easy to handle, and aligned with popular tastes.

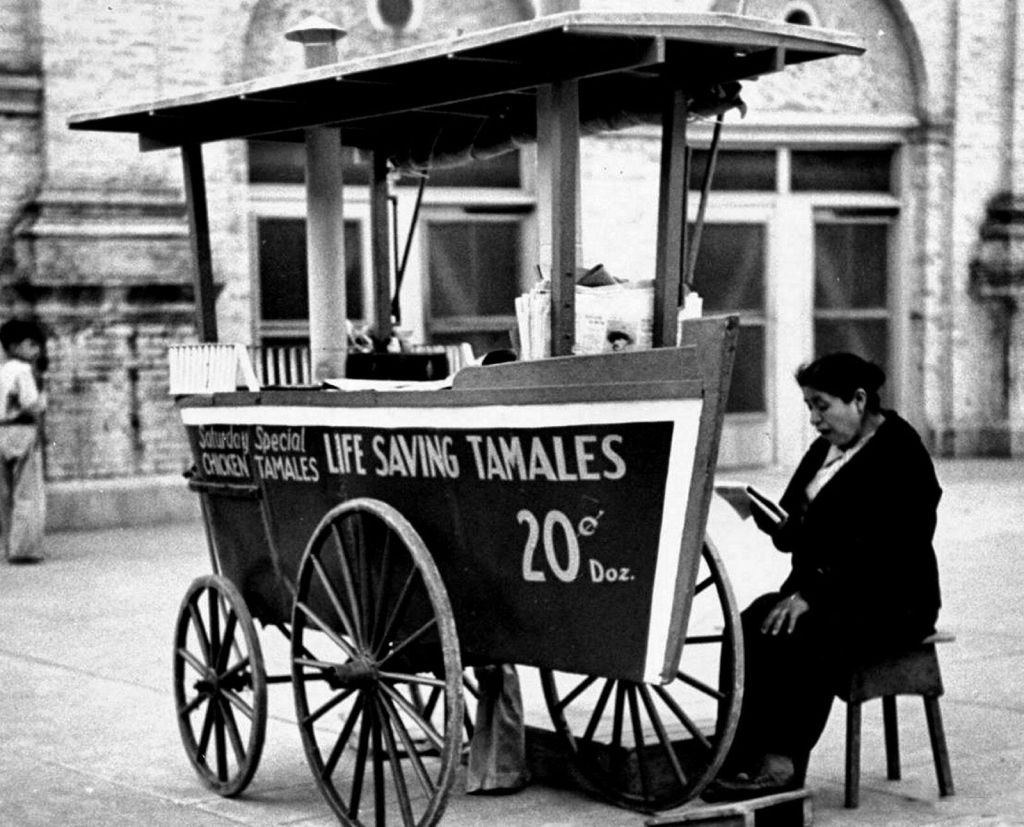

For many years tamales occupied a prominent role as street food in the U.S., starting in the 1880s in parts of the country where many Mexican-Americans lived such as California and Texas. [above photo, Sacramento CA, 1937]

While Mexicans remained prominent in the tamale trade, both producing and selling them, people with a range of ethnic backgrounds joined in. Sellers might also be U.S. born or recent immigrants of Irish, German, even Danish ancestry. A NY Tribune story described a NYC tamale vendor with red hair and a brogue. Italian immigrants seem to have been particularly prominent among street sellers. And, a story in Overland Monthly reported that in the copper region of Idaho in the early 20th century “the Syrian quarter . . . is the seat of the hot tamale industry.”

Chicken was the favorite tamale filling, though critics often wondered if that was what they were eating. The filling was surrounded by a corn mush mixture that was rolled in a corn husk and steamed. Most tamales were sold in cities and towns where finding a supply of corn husks could be a problem. But by the early 1900s, a market in husks had developed, with some farmers finding them quite profitable.

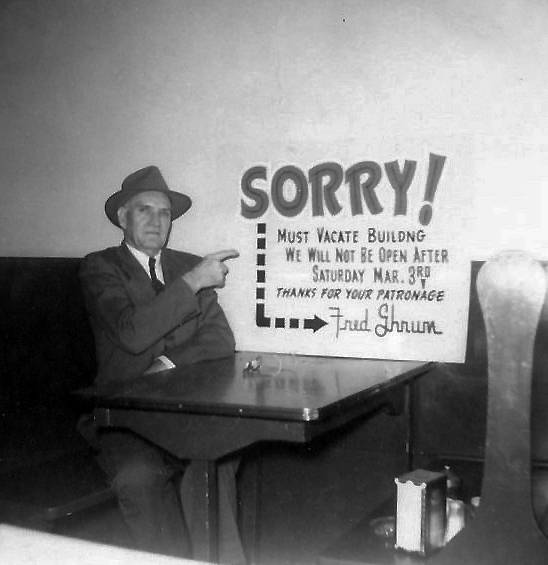

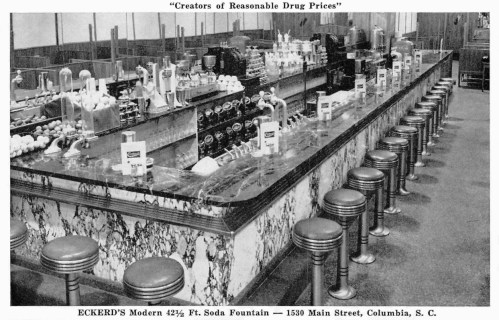

The corn husk specialty grew as companies got into the canned tamale business, beginning around in the early 1900s. Some, such as the X. L. N. T. Company of Los Angeles, delivered tamales to homes [above, 1908]. A publication of the California State Federation of Labor claimed that by 1916 canned tamales had become so popular that the leading packing company was selling 4,000,000 cans of its I. X .L. brand annually. In Mexico, tamales were wrapped in the white inner husks; the packing industry, by contrast, bleached the green husks. Still, bleaching was better than unsanitary tamale production such as that uncovered in Ohio in 1900 where the corn husks were obtained from old mattresses. As might be expected the canned tamale business cut into street trade.

Certainly there were people who regarded tamales sold on the street as unsanitary, acceptable only to drunken men (no doubt revealing a bias against immigrants). Sellers were criticized for disrupting the peace at night as they called out their wares. Cities and towns tried to regulate them out of existence, sometimes succeeding. It was not an easy business overall. Selling tamales on the street was a rough job, conducted mainly after dark. Vendors risked frequent encounters with attackers and robbers, and it was not unusual for them to be seriously injured or killed.

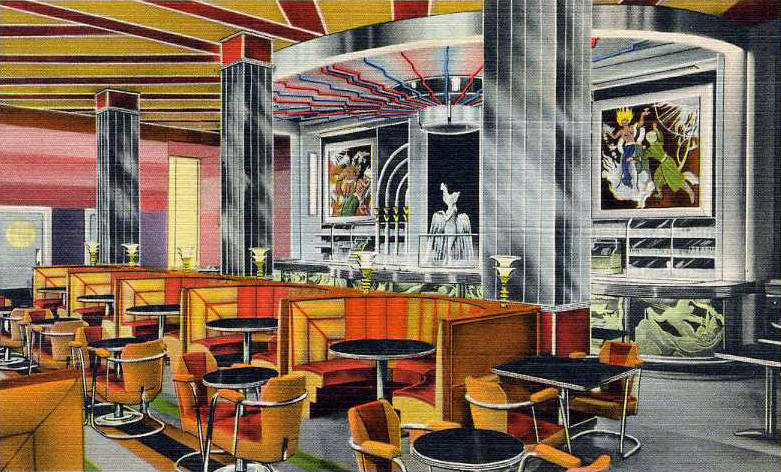

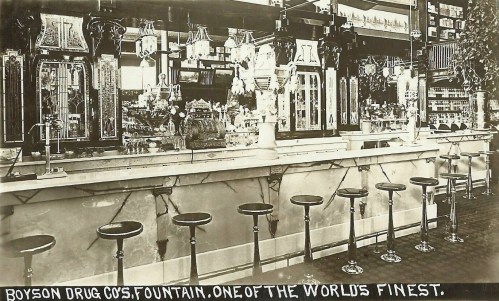

During their peak popularity extending from the 1890s up to WWII, tamales spread across the U.S., but they were always most common in the West. Originally sold out of kettles in which they were kept warm by a separate hot water basin at the bottom, they soon migrated to lunch wagons and stands. [above, Brownsville TX, 1938] Unlike chop suey, spaghetti, chili, frankfurters, and hamburgers, they did not quite win full American “citizenship,” and were not often found on restaurant menus outside of the West and, to a lesser extent, the Midwest and South.

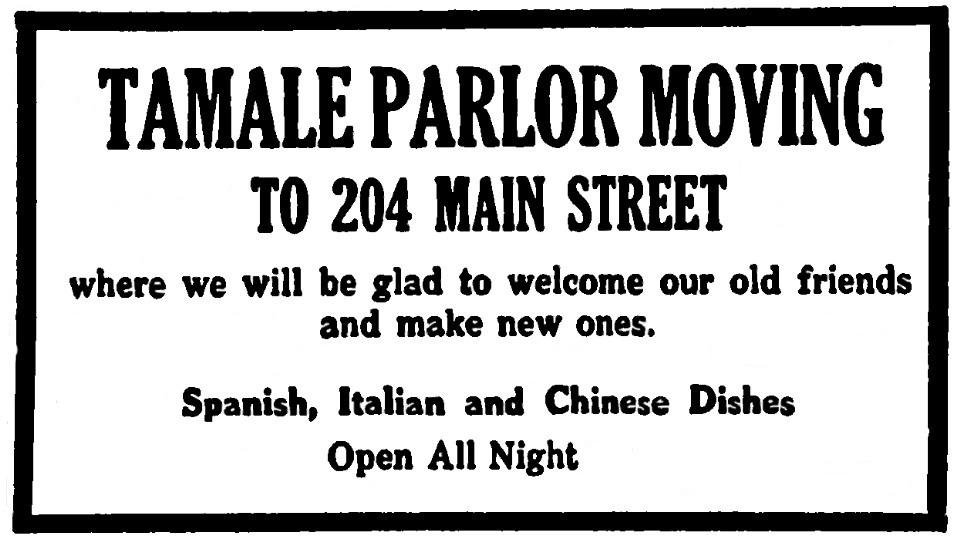

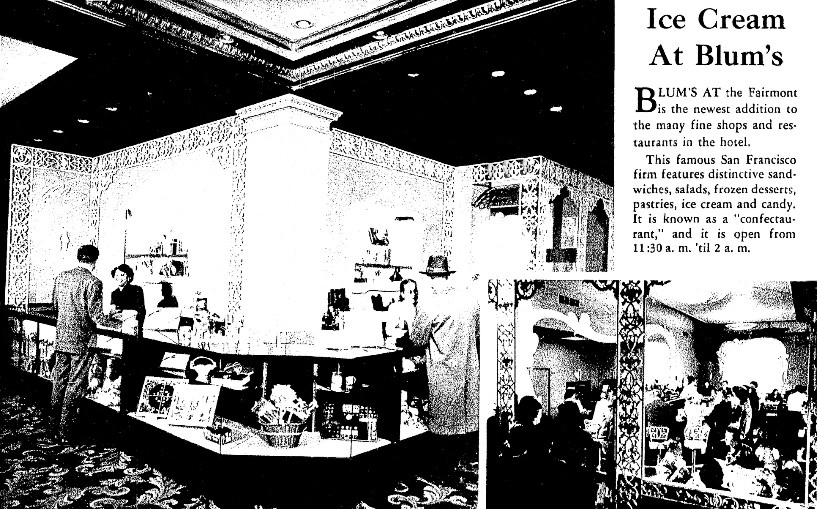

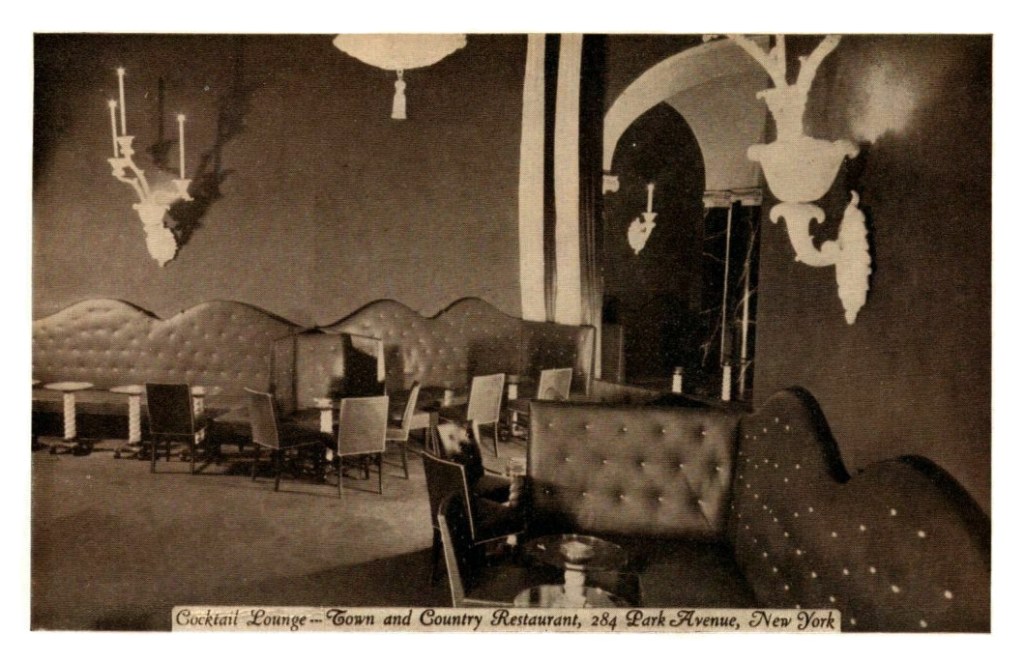

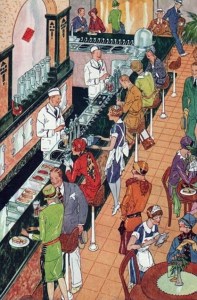

Tamales figured on menus a bit differently than they would today when a restaurant serving them is almost certainly run by someone of Mexican descent or is a corporate Mexican-themed chain. In either case, the menu is dominated by what are regarded as Mexican dishes. It wasn’t always this way. Although proprietors with ties to Mexico have always been prominent, the owners of many earlier tamale grottoes, parlors, shops, and stands were, like the street peddlers, a diverse lot. I have found proprietors named Mohamed, Truzzolino, and Stubendorff. Menus could also be diverse and include lobster tails, oysters, or banana cream pie. A Klamath Falls OR tamale parlor combined Mexican dishes with those of Italy and China [advertisement pictured above, 1921]. Tamales turned up in unexpected places, such as the California Pig ‘n’ Whistle confectionery chain and, in 1909, the Marshall Field department store tea room in Chicago.

The custom of selling tamales from kettles, carts, and stands might have largely died out sooner if it hadn’t been for the 1930s Depression, when many people were desperate for even a trickle of income. The 1937 Roadman’s Guide, a little booklet full of ideas for money-making schemes that could be launched out of the home, gave a detailed recipe for making tamales.

Not that tamales have entirely disappeared today. They can be found as part of family holiday celebrations, at Western tamale festivals, and for sale by street vendors here and there.

© Jan Whitaker, 2021

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.