Marie Marchand, whose business name was Romany Marie, was taken aback in the 1950s when a Greenwich Village restaurateur declined to host a dinner for Marie’s artist friends on the grounds they would occupy the tables too long. In a 1960 interview recorded in Romany Marie, Queen of Greenwich Village by Robert Schulman, Marie reflected, “It was a little shock to me. Poor dear, she felt she had to have turnover, she was in the restaurant business, not in the venture of maintaining a center for lingering tempo.”

Marie Marchand, whose business name was Romany Marie, was taken aback in the 1950s when a Greenwich Village restaurateur declined to host a dinner for Marie’s artist friends on the grounds they would occupy the tables too long. In a 1960 interview recorded in Romany Marie, Queen of Greenwich Village by Robert Schulman, Marie reflected, “It was a little shock to me. Poor dear, she felt she had to have turnover, she was in the restaurant business, not in the venture of maintaining a center for lingering tempo.”

For someone such as Marie who had herself been in the restaurant business for over 30 years, this would seem to be an odd reaction. But hers were odd restaurants – she preferred to call them centers – where patrons were encouraged to linger. If they lacked money for a meal, and they fit her criteria as creative spirits, she let them eat for free. Luckily, she had a brother who helped her out financially because hers was not a lucrative business. On the other hand, she encouraged and helped sustain dozens of artists and creators such as Buckminster Fuller, Burl Ives, Stuart Davis, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and John Sloan (one of the many artists who painted her portrait – pictured above).

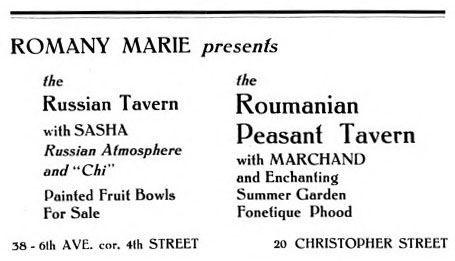

Marie, who as a teenager came to the US from Romania in 1901, said she patterned her taverns (so-called though she served no alcoholic drinks) after the inn her mother ran for gypsies in the old country. To honor her mother, Marie dressed as a gypsy and usually decorated in rococo style with peasant scarves, batiks, pottery, and her patrons’ paintings. Several of the 11 locations she occupied over the years featured fireplaces, which to the horror of health inspectors she used for broiling steaks.

Marie, who as a teenager came to the US from Romania in 1901, said she patterned her taverns (so-called though she served no alcoholic drinks) after the inn her mother ran for gypsies in the old country. To honor her mother, Marie dressed as a gypsy and usually decorated in rococo style with peasant scarves, batiks, pottery, and her patrons’ paintings. Several of the 11 locations she occupied over the years featured fireplaces, which to the horror of health inspectors she used for broiling steaks.

After working initially in the garment industry Marie brought her mother and sisters to New York. The family lived on the lower East Side near the Ferrer School which offered workers free adult education. She became involved with the school where she met artists and thinkers who later became her patrons and, sometimes, volunteer waiters. In 1914 she opened her first place in the Village’s Sheridan Square. Amenities were sorely lacking, with both stairway and toilet facilities located outdoors. For years she had no electricity, candles furnishing the only lighting.

In 1915 she moved to 20 Christopher Street and it was at this location, the one she occupied the longest, that her name became well known. Another location of renown was 15 Minetta Street, with an interior designed by Buckminster Fuller in the late 1920s. In the 1960 interview Marie quoted Fuller as saying, “I’m going to fix up this place in a Dymaxion way.” He outfitted the restaurant with canvas sling chairs, “aeroplane tables,” and aluminum cone lights. Instead of the darkness her patrons were accustomed to, Fuller lit the place up by painting the walls silver. Sculptor Isamu Noguchi assisted (“Bucky got me to help him with painting the place up solar.”). Everyone disliked the brightness, the tables wobbled when food was placed on them, and the chairs collapsed when sat on. The experiment failed but Marie promised Fuller one free meal a day for the rest of his life, a benefit that carried him through the Depression.

In 1915 she moved to 20 Christopher Street and it was at this location, the one she occupied the longest, that her name became well known. Another location of renown was 15 Minetta Street, with an interior designed by Buckminster Fuller in the late 1920s. In the 1960 interview Marie quoted Fuller as saying, “I’m going to fix up this place in a Dymaxion way.” He outfitted the restaurant with canvas sling chairs, “aeroplane tables,” and aluminum cone lights. Instead of the darkness her patrons were accustomed to, Fuller lit the place up by painting the walls silver. Sculptor Isamu Noguchi assisted (“Bucky got me to help him with painting the place up solar.”). Everyone disliked the brightness, the tables wobbled when food was placed on them, and the chairs collapsed when sat on. The experiment failed but Marie promised Fuller one free meal a day for the rest of his life, a benefit that carried him through the Depression.

In addition to Romanian dishes such as meat pies and cabbage rolls, Marie specialized in strong coffee which she advertised as Café Noir à la Turque. Her signature dish was ciorbă, a soup of vegetables, meatballs, eggs, lemon juice, and sour cream. Marie’s husband Arnold, a difficult man who was known to deliberately break dishes and otherwise sabotage her efforts, rendered this dish on his phonetic menu as “Tchorbah, peasant soop.” A menu by him also listed “Boylt Beeph wit been’s & hors radish,” and “Lone Guy Land Greens.”

In addition to Romanian dishes such as meat pies and cabbage rolls, Marie specialized in strong coffee which she advertised as Café Noir à la Turque. Her signature dish was ciorbă, a soup of vegetables, meatballs, eggs, lemon juice, and sour cream. Marie’s husband Arnold, a difficult man who was known to deliberately break dishes and otherwise sabotage her efforts, rendered this dish on his phonetic menu as “Tchorbah, peasant soop.” A menu by him also listed “Boylt Beeph wit been’s & hors radish,” and “Lone Guy Land Greens.”

Marie continued in the restaurant business until 1946 when she retired to care for Arnold. Each time Marie moved her restaurant she announced it with a sign which said “The caravan has moved.” Its last move was to 49 Grove Street.

© Jan Whitaker, 2010

What could be more starkly different from the somber coffee shops of today with their earnest and wired denizens than the beatnik coffeehouses of the 1950s? Could Starbucks be anything but square to the beat generation?

What could be more starkly different from the somber coffee shops of today with their earnest and wired denizens than the beatnik coffeehouses of the 1950s? Could Starbucks be anything but square to the beat generation? Although the word beatnik came into usage around 1958 (inspired partly by Sputnik), the phenomenon of dropping out of the “rat race” to lead an existentialist, non-consumerist life was part of the aftermath of World War II akin to the “Lost Generation” after World War I. The first coffeehouses sprang up in Greenwich Village in the late 1940s, but the beats weren’t averse to hanging out in cafeterias either — their “Paris sidewalk restaurant thing of the time.” When coffeehouses began levying cover charges for performances, beatniks tended to drop out of them too.

Although the word beatnik came into usage around 1958 (inspired partly by Sputnik), the phenomenon of dropping out of the “rat race” to lead an existentialist, non-consumerist life was part of the aftermath of World War II akin to the “Lost Generation” after World War I. The first coffeehouses sprang up in Greenwich Village in the late 1940s, but the beats weren’t averse to hanging out in cafeterias either — their “Paris sidewalk restaurant thing of the time.” When coffeehouses began levying cover charges for performances, beatniks tended to drop out of them too. The heyday of the coffeehouse was the late 1950s into the early 1960s. Few did much cooking so they weren’t restaurants in the true sense, but many of them offered light food such as salami sandwiches (on exotic Italian bread) and cheesecake, along with “Espresso Romano,” the most expensive coffee ever seen in the U.S. up til then. Of course the charge for coffee was more a rent payment than anything else since patrons sat around for hours while consuming very little. Other then-unfamiliar food offerings included cannolis at La Gabbia (The Birdcage) in Queens, Swiss cuisine at Alberto’s in Westwood CA, Irish stew at Coffee ’n’ Confusion in D.C., les fromages at Café Oblique in Chicago, “Suffering Bastard Sundaes” at The Bizarre in Greenwich Village, and snacks such as chocolate-covered ants and caterpillars at the Green Spider in Denver.

The heyday of the coffeehouse was the late 1950s into the early 1960s. Few did much cooking so they weren’t restaurants in the true sense, but many of them offered light food such as salami sandwiches (on exotic Italian bread) and cheesecake, along with “Espresso Romano,” the most expensive coffee ever seen in the U.S. up til then. Of course the charge for coffee was more a rent payment than anything else since patrons sat around for hours while consuming very little. Other then-unfamiliar food offerings included cannolis at La Gabbia (The Birdcage) in Queens, Swiss cuisine at Alberto’s in Westwood CA, Irish stew at Coffee ’n’ Confusion in D.C., les fromages at Café Oblique in Chicago, “Suffering Bastard Sundaes” at The Bizarre in Greenwich Village, and snacks such as chocolate-covered ants and caterpillars at the Green Spider in Denver.

After passing up Bamboo Isle (“Strictly Kosher Turkey Sandwiches, Fifteen Cents”), he heads to what was probably Mother Goose. “Finally, in an eatery built in the shape of an old boot I was able to procure a satisfying meal of barbecued pork fritters and orangeade for seventy-five cents. Charming platinum-haired hostesses in red pajamas and peaked caps added a note of color to the scene, and a gypsy orchestra played Victor Herbert on musical saws.”

After passing up Bamboo Isle (“Strictly Kosher Turkey Sandwiches, Fifteen Cents”), he heads to what was probably Mother Goose. “Finally, in an eatery built in the shape of an old boot I was able to procure a satisfying meal of barbecued pork fritters and orangeade for seventy-five cents. Charming platinum-haired hostesses in red pajamas and peaked caps added a note of color to the scene, and a gypsy orchestra played Victor Herbert on musical saws.” In a 1936 photo series called “Chamber of American Horrors” for which he wrote captions he describes Mother Goose as a place where “Inside, kiddies from six to sixty, most of whom are indistinguishable from each other, gnaw sizzling steaks and discuss their movie favorites.” Other eating places included in the Chamber were the Toed Inn (“tasty combinations of avocado and bacon, pimento and peanut butter”), the Laughing Pig Barbecue Pit (“Etched in red and blue neon lights against the velvety southern California night, it can be seen and avoided for miles.”), and the Pup (“The most ravenous appetite fades before this elaborate cheese dream.”).

In a 1936 photo series called “Chamber of American Horrors” for which he wrote captions he describes Mother Goose as a place where “Inside, kiddies from six to sixty, most of whom are indistinguishable from each other, gnaw sizzling steaks and discuss their movie favorites.” Other eating places included in the Chamber were the Toed Inn (“tasty combinations of avocado and bacon, pimento and peanut butter”), the Laughing Pig Barbecue Pit (“Etched in red and blue neon lights against the velvety southern California night, it can be seen and avoided for miles.”), and the Pup (“The most ravenous appetite fades before this elaborate cheese dream.”).

Don Dickerman was obsessed with pirates. He took every opportunity to portray himself as one, beginning with a high school pirate band. As an art student in the teens he dressed in pirate garb for Greenwich Village costume balls. Throughout his life he collected antique pirate maps, cutlasses, blunderbuses, and cannon. His Greenwich Village nightclub restaurant, The Pirates’ Den, where colorfully outfitted servers staged mock battles for guests, became nationally known and made him a minor celebrity.

Don Dickerman was obsessed with pirates. He took every opportunity to portray himself as one, beginning with a high school pirate band. As an art student in the teens he dressed in pirate garb for Greenwich Village costume balls. Throughout his life he collected antique pirate maps, cutlasses, blunderbuses, and cannon. His Greenwich Village nightclub restaurant, The Pirates’ Den, where colorfully outfitted servers staged mock battles for guests, became nationally known and made him a minor celebrity.

Over time he ran five clubs and restaurants in New York City. After failing to make a living as a toy designer and children’s book illustrator, he opened a tea room in the Village primarily as a place to display his hand-painted toys. It became popular, expanded, and around 1917 he transformed it into a make-believe pirates’ lair where guests entered through a dark, moldy basement. Its fame began to grow, particularly after 1921 when Douglas Fairbanks recreated its atmospheric interior for his movie The Nut. He also ran the Blue Horse (pictured), the Heigh-Ho (where Rudy Vallee got his start), Daffydill (financed by Vallee), and the County Fair.

Over time he ran five clubs and restaurants in New York City. After failing to make a living as a toy designer and children’s book illustrator, he opened a tea room in the Village primarily as a place to display his hand-painted toys. It became popular, expanded, and around 1917 he transformed it into a make-believe pirates’ lair where guests entered through a dark, moldy basement. Its fame began to grow, particularly after 1921 when Douglas Fairbanks recreated its atmospheric interior for his movie The Nut. He also ran the Blue Horse (pictured), the Heigh-Ho (where Rudy Vallee got his start), Daffydill (financed by Vallee), and the County Fair. On a Blue Horse menu of the 1920s Don’s mother is listed as manager. Among the dishes featured at this jazz club restaurant were Golden Buck, Chicken a la King, Tomato Wiggle, and Tomato Caprice. Drinks (non-alcoholic) included Pink Goat’s Delight and Blue Horse’s Neck. Ice cream specials also bore whimsical names such as Green Goose Island and Mr. Bogg’s Castle. At The Pirates’ Den a beefsteak dinner cost a hefty $1.25. Also on the menu were chicken salad, sandwiches, hot dogs, and an ice cream concoction called Bozo’s Delight. A critic in 1921 concluded that, based on the sky-high menu tariffs and the “punk food,” customers there really were at the mercy of genuine pirates.

On a Blue Horse menu of the 1920s Don’s mother is listed as manager. Among the dishes featured at this jazz club restaurant were Golden Buck, Chicken a la King, Tomato Wiggle, and Tomato Caprice. Drinks (non-alcoholic) included Pink Goat’s Delight and Blue Horse’s Neck. Ice cream specials also bore whimsical names such as Green Goose Island and Mr. Bogg’s Castle. At The Pirates’ Den a beefsteak dinner cost a hefty $1.25. Also on the menu were chicken salad, sandwiches, hot dogs, and an ice cream concoction called Bozo’s Delight. A critic in 1921 concluded that, based on the sky-high menu tariffs and the “punk food,” customers there really were at the mercy of genuine pirates.

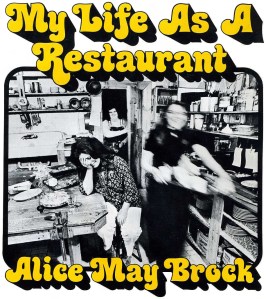

In interviews and in her two books Alice espoused the value of fresh ingredients, garlic, meals with friends, and an experimental approach to cooking. Her words convey a free-wheeling, irreverent outlook. Some examples:

In interviews and in her two books Alice espoused the value of fresh ingredients, garlic, meals with friends, and an experimental approach to cooking. Her words convey a free-wheeling, irreverent outlook. Some examples:

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.