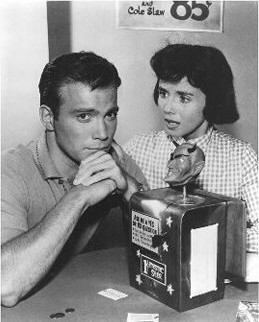

A 1960 episode of The Twilight Zone, “The Nick of Time,” was set in a restaurant outfitted with a devilish fortune-telling device. The restaurant, supposedly in Ohio, was ordinary and undistinguished, with booths and laminated table tops.

A 1960 episode of The Twilight Zone, “The Nick of Time,” was set in a restaurant outfitted with a devilish fortune-telling device. The restaurant, supposedly in Ohio, was ordinary and undistinguished, with booths and laminated table tops.

The story’s writer chose a common name for it, one found in practically every city and small town across the entire United States: the Busy Bee.

I “collect” this name. To me it resonates with the typical 20th-century eating place. Judging from advertisements for eateries called The Busy Bee, they staked their reputations on being clean, economical, briskly efficient, and friendly.

I also find the name interesting because it is entirely divorced from place, proprietor’s ethnicity, and type of cuisine. Yet I’ve found that many restaurants of this name had proprietors who were of Polish, Italian, or Greek ethnic origins.

In the 19th century it was typical for restaurants to go by their proprietor’s surname. Over the 20th century, by contrast, many restaurants adopted “made up” names that were intended to suggest something positive, appealing, or at least memorable. I suspect that one of the factors propelling this change was the chance to background the ethnicity of the proprietor, particularly around World War I when much of the country became intolerant of those not native born. Busy Bee became one of the most common names around.

Also, restaurants owned by Greek-Americans, of which there were very many, were often run by multiple partners. It would be somewhat unwieldy if, for instance, the proprietors of the Busy Bee in Monessen PA in 1915 had decided to call their restaurant Chrysopoulos, Boulageris, Paradise, & Lycourinos. They might have taken the liberty of dubbing their establishment Four Brothers from Mykonos but they chose Busy Bee instead. [pictured: Busy Bee in Winchester VA — its proprietor, James Pappas, was born in Greece ca. 1889]

Also, restaurants owned by Greek-Americans, of which there were very many, were often run by multiple partners. It would be somewhat unwieldy if, for instance, the proprietors of the Busy Bee in Monessen PA in 1915 had decided to call their restaurant Chrysopoulos, Boulageris, Paradise, & Lycourinos. They might have taken the liberty of dubbing their establishment Four Brothers from Mykonos but they chose Busy Bee instead. [pictured: Busy Bee in Winchester VA — its proprietor, James Pappas, was born in Greece ca. 1889]

I have yet to find a Chinese restaurant called the Busy Bee but I’ll keep looking – I know there had to be a few.

Among many locations, I’ve found Busy Bees in Mobile AL as early as 1898, in Bisbee AZ in 1915, and in New York City’s Bowery, for decades presided over by Max Garfunkel. It was at Max’s Busy Bee, in 1917, that alumni of the Short Story Correspondence Schools of North America convened to greet the author of “Ten Thousand Snappy Synonyms for ‘Said He.’” Many Busy Bees became headquarters for meetings of business, civic, and social clubs.

Busy Bees were not known for any particular culinary specialties, offering instead home cooking favorites plus the inevitable chili and other Americanized foreign dishes such as spaghetti and chop suey. The four popular Busy Bees in Columbus OH, nonetheless, had an attractive array of warm weather choices on their June 29, 1909, menu which included Spring Vegetable Salad (10 cents), as well as Blackberries or Sliced Peaches in Cream (10 cents) and Fresh Peach Ice Cream (15 cents).

The Busy Bee name lives on even today, though perhaps less robustly. I was surprised there was not a single Busy Bee mentioned in Joanne Raetz Stuttgen’s books on contemporary “down home” cafes in Wisconsin and Indiana.

Is there a common restaurant name all around us today that will come to characterize the 21st century?

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.