It was an orphaned family that had gone through some difficult times that developed one of the early, very successful chains of cafeterias in California.

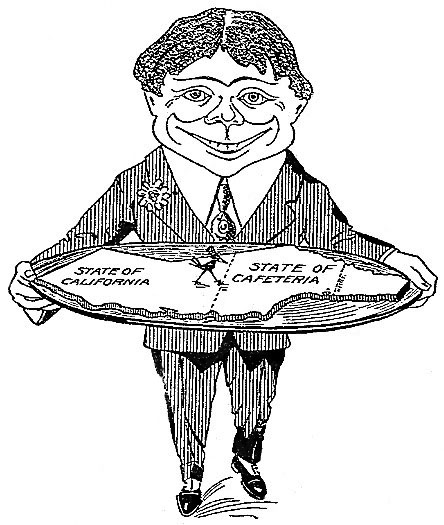

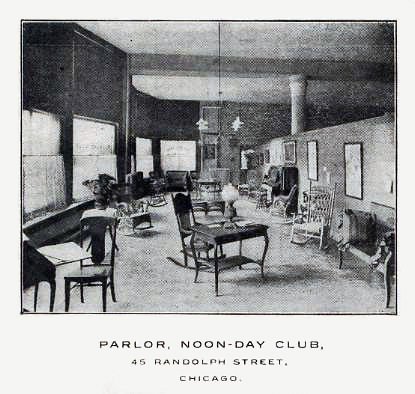

The chain of Boos Brothers cafeterias was one of the first in Los Angeles, contributing to the flood of cafeterias that soon appeared in that city and elsewhere in Southern California. Californians to the north ridiculed the trend, referring to Los Angeles and southern California as the “State of Cafeteria.” It’s true, of course, that cafeterias have never been seen as fashionable and sophisticated.

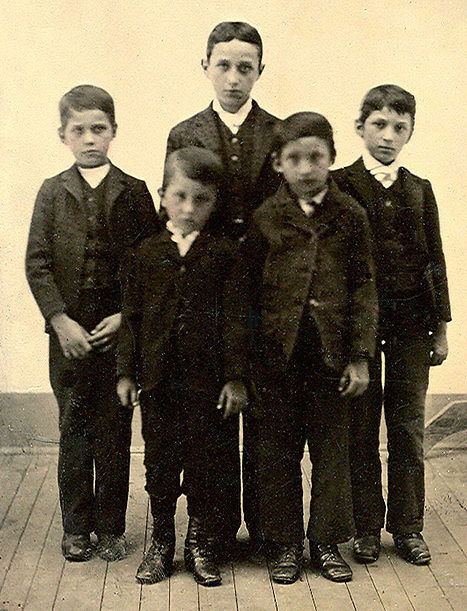

The Boos [probably pronounced Boes] family story reads like a fictional tale. The Moscow, Ohio, family of nine children were orphaned when both parents died in the late 1880s, followed by the eldest son’s demise two years later. That left Horace, about 19, as caretaker of his three brothers and four sisters. In his will, their father had expressed a wish that they all stay together, live in the family home, and be self supporting. They followed his wishes except for staying in their small hometown. At some point Horace moved the family to Cincinnati where he got a job as a typesetter for the Cincinnati Enquirer. He and his brothers, and at least one sister, also operated a grocery story, then a hotel and restaurant in Cincinnati.

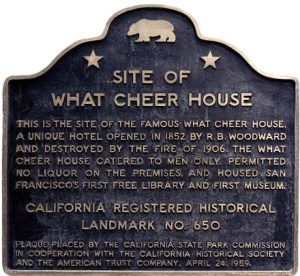

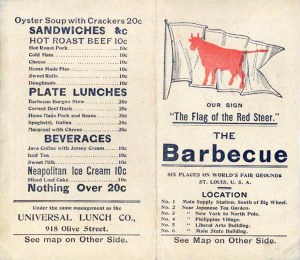

Before the brothers, and some of the sisters, moved to California in 1906 they had also lived briefly in Rochester, New York City, and St. Louis, operating restaurants in all of them, including a lunchroom at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

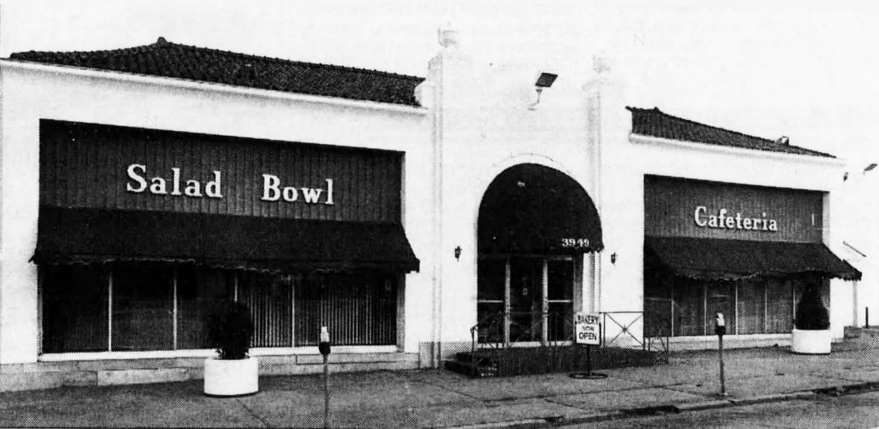

Once in California they acquired a ranch in San Gabriel, offering eggs for sale in a 1906 advertisement. By August of that year they had opened their first cafeteria in Los Angeles. They also continued to operate the ranch, supplying their restaurants with eggs into the 1920s.

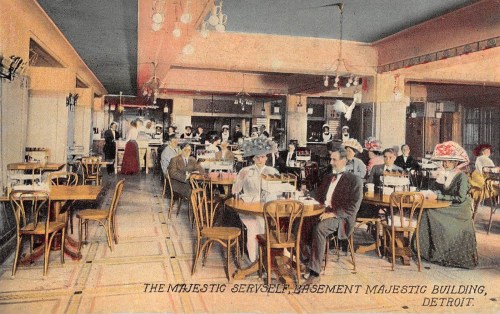

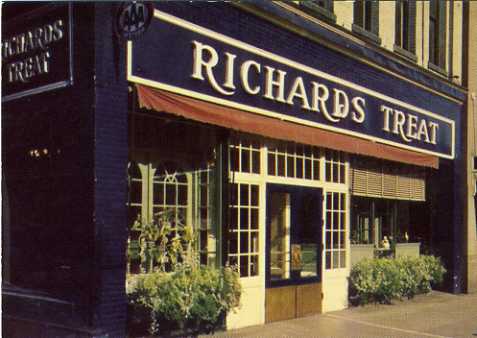

By 1909 they had expanded to three cafeterias. Judging from postcards like the one here, the early cafeterias may have been exceptionally sanitary and well outfitted but had a somewhat functional appearance. Gradually their cafeterias became more decorative, particularly when they moved into buildings they had built.

In 1922 they opened a newly built cafeteria at 618 S. Olive decorated in what they described as Spanish and Moorish style. An advertisement celebrated its interior: “Accentuating the impressive spaciousness of the place, are three arched windows of great height in the north wall. In corresponding positions in the south wall, equivalent in number and size, are mural paintings of exquisite technique, depicting with historical exactness, Cortez before Montezuma.”

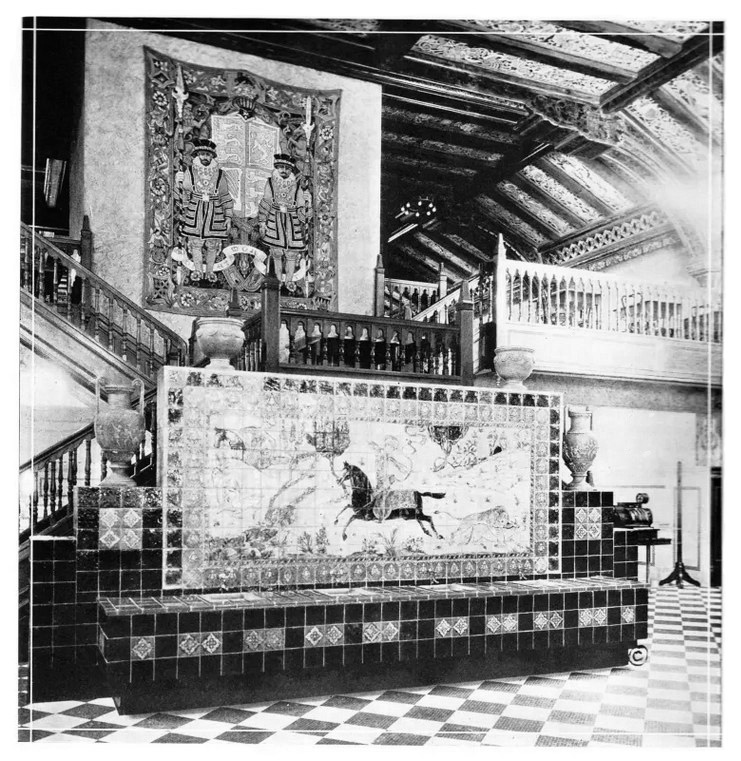

The newest, and last, cafeteria, built at 530 S. Hill in 1926 — a location previously occupied by a failed B&M Cafeteria — was custom-built and featured the largest orchestra, one of 9 pieces. It also was fitted with rest rooms filled with upholstered arm chairs and settees. A row of water fountains referred to as a “Persian fountain” was backed by a large and impressive scene painted on tiles [shown here].

In 1927 the cafeteria company celebrated its 20th anniversary, publishing a booklet called “Glancing Back Along the Cafeteria Trail.” At that point the business operated six cafeterias in Los Angeles and one on the island of Catalina opened in 1918.

The booklet celebrated their success and gave some idea of what it took, such as purchasing 870,000 pounds of beef per year and 40,800 chickens. An estimate of how many acres it would take to grow the fruits and vegetables used by the chain came to 20,000. The Boos used only fresh vegetables, nothing canned. All but one of their locations had live orchestral music.

Surprisingly, the year after the celebratory booklet was published, the brothers sold the chain to the Childs corporation, including all six cafeterias in Los Angeles and the one on Catalina Island. At that point the six L.A. cafeterias were reputedly serving 10M meals a year. The sale to Childs, which kept the Boos name, was said to net $8M for the three remaining brothers. Horace Boos had died the previous year and it’s possible that might have motivated the sale.

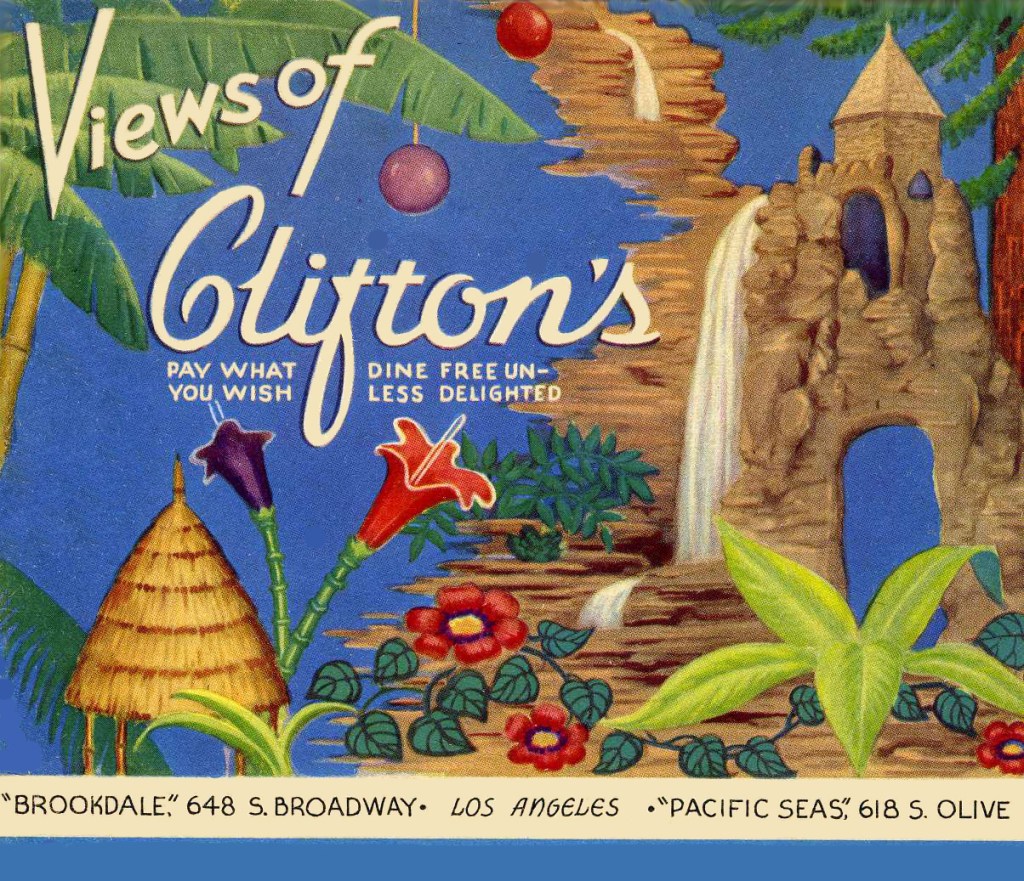

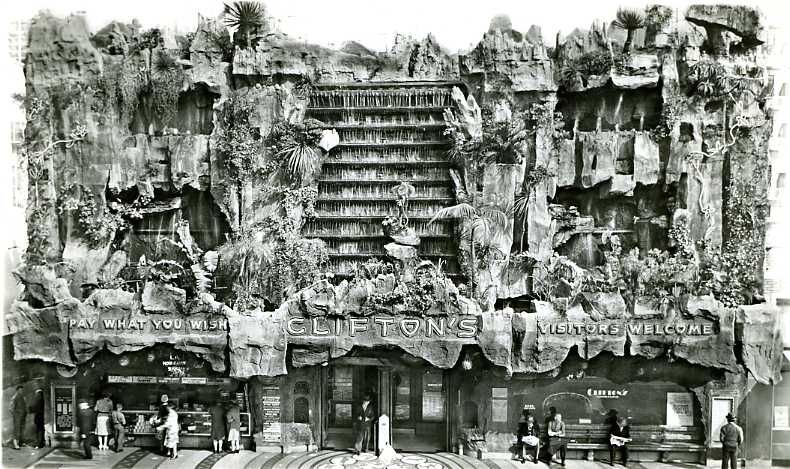

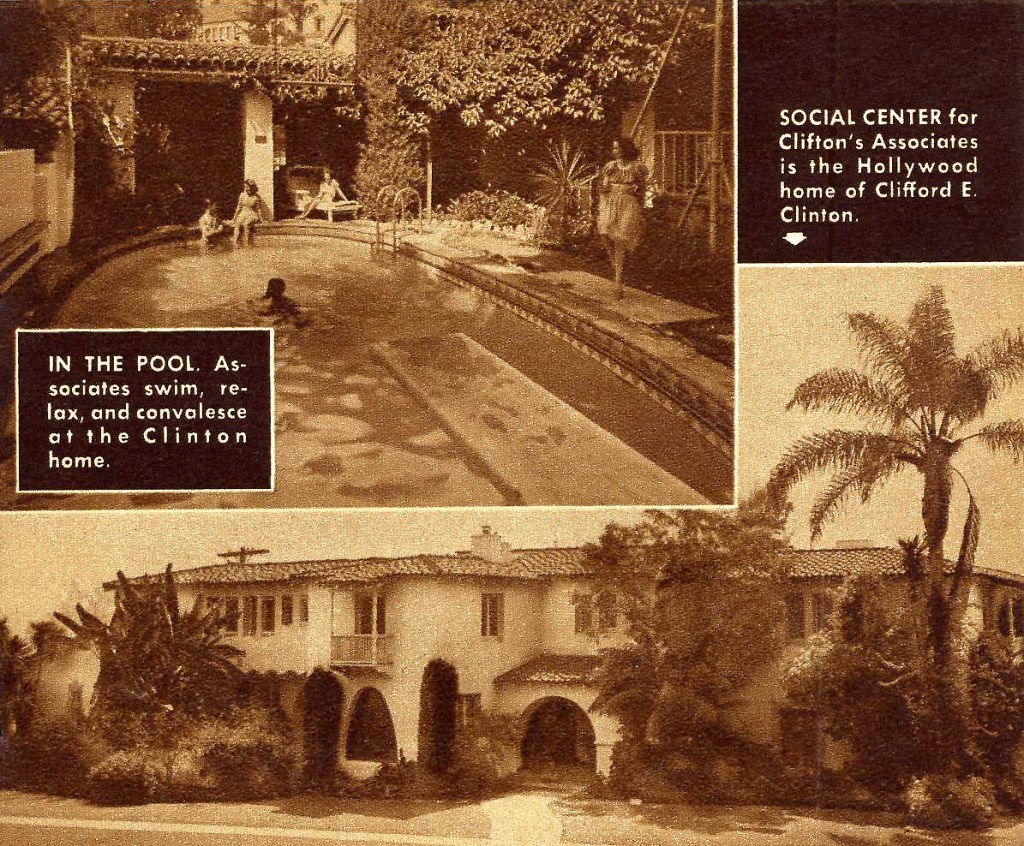

In the Depression, Childs sold their Boos holdings, two going to Clifford Clinton of Clifton’s Cafeterias fame, and two returning to the Boos brothers, according to some accounts. Other reports, confusingly, had the brothers buying back all the cafeterias. Whichever was the case, the only one that seemed to reopen under the control of the Boos brothers was the cafeteria at 530 S. Hill. During the Depression it met the needs of people with little money, offering low-priced dishes such as soup and spaghetti for 8 cents and most vegetables for 7 cents.

The S. Hill Boos Brothers cafeteria was still in business as late as 1955, advertising in the Los Angeles Times as “The Original.” But at some point it acquired a new owner doing business as Green’s Cafeteria. In 1960 Green’s was out of business and the equipment was auctioned.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.