Mary Elizabeth Evans, for whom the landmark tea room was named, began her career in 1900 at age 15 as a small grocer and candymaker in Syracuse. After one year in business she cleared the then-handsome sum of $1,000 which she contributed to the support of her family while supervising a growing crew of helpers which included her two younger sisters who served as clerks and her brother who made deliveries.

Her family, though in seriously reduced circumstances, had valuable social connections. Her late grandfather had been a judge, her uncle an actor, and her departed father a music professor. That may help explain how she achieved success so rapidly – and why her story garnered so much publicity. By 1904 several elite NYC clubs and hotels sold her candy and soon thereafter it was for sale at summer resorts such as Asbury Park and Newport and in stores as far away as Chicago and Grand Rapids. In 1913 the all-women Mary Elizabeth company, which included her mother and sisters Martha and Fanny, was prosperous enough to sign a 21-year lease totaling nearly $1 million for a prestigious Fifth Avenue address close to Altman’s, Best & Co., Lord & Taylor, and Franklin-Simon’s.

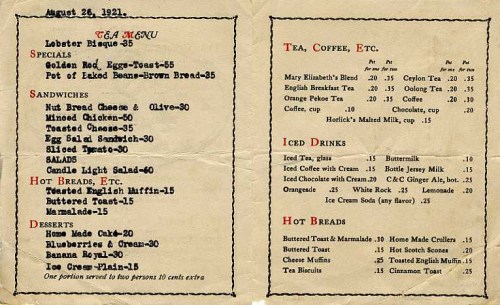

By the early teens the candy store had expanded into a charming tea room with branches in Newport and two in Boston, one on Temple Street and the other in the basement of the Park Street Church near the Boston Common (pictured ca. 1916). Like other popular tea rooms of the era, Mary Elizabeth’s bucked the tide of chain stores and standardized products by emphasizing food preparation from scratch. Known for “real American food served with a deft feminine touch,” Fanny Evans said the tea rooms catered to women’s tastes in “fancy, unusual salads,” “delicious home-made cakes,” and dishes such as “creamed chicken, sweetbreads, croquettes, timbales and patties.” For many decades, the NYC Mary Elizabeth’s was known especially for its crullers (long twisted doughnuts).

By the early teens the candy store had expanded into a charming tea room with branches in Newport and two in Boston, one on Temple Street and the other in the basement of the Park Street Church near the Boston Common (pictured ca. 1916). Like other popular tea rooms of the era, Mary Elizabeth’s bucked the tide of chain stores and standardized products by emphasizing food preparation from scratch. Known for “real American food served with a deft feminine touch,” Fanny Evans said the tea rooms catered to women’s tastes in “fancy, unusual salads,” “delicious home-made cakes,” and dishes such as “creamed chicken, sweetbreads, croquettes, timbales and patties.” For many decades, the NYC Mary Elizabeth’s was known especially for its crullers (long twisted doughnuts).

Mary Elizabeth distinguished herself as a patriot during the First World War by producing a food-conservation cookbook of meatless, wheatless, and sugarless recipes, and by volunteering to help the Red Cross develop diet kitchens in France. After her marriage to a wealthy Rhode Island businessman in 1920 she apparently played a reduced management role in the business.

In its later years the NYC restaurant passed out of the family’s hands and began to decline, culminating in an ignominious Health Department citation in 1985.

© Jan Whitaker, 2008

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.