Until electricity became common no one thought dining by candlelight was the least bit romantic. In the later 19th century any restaurant that acquired electricity made a big bragging deal of it. A Chicago restaurant called The New York Kitchen boasted in 1888 that its dining room was “brilliantly lighted by the Mather Incandescent Electric System.” In the early 20th century going places with bright light was fashionable, especially because it turned restaurants into stages on which to be seen and to covertly stare at others.

Until electricity became common no one thought dining by candlelight was the least bit romantic. In the later 19th century any restaurant that acquired electricity made a big bragging deal of it. A Chicago restaurant called The New York Kitchen boasted in 1888 that its dining room was “brilliantly lighted by the Mather Incandescent Electric System.” In the early 20th century going places with bright light was fashionable, especially because it turned restaurants into stages on which to be seen and to covertly stare at others.

But there were some ultra-refined people who considered the glare of bright light vulgar. Etiquette expert Emily Holt recommended in1902 that candles be used instead of gas or electric chandeliers for home dinner parties lest the dinner resemble a “blazing feast … in some hotel restaurant.” At that time restaurant patrons who wanted mellow light could choose a place such as Sherry’s in New York where wall sconces gave off gentle illumination and candles topped by artistic shades reposed on each table. So private! So French!

But there were some ultra-refined people who considered the glare of bright light vulgar. Etiquette expert Emily Holt recommended in1902 that candles be used instead of gas or electric chandeliers for home dinner parties lest the dinner resemble a “blazing feast … in some hotel restaurant.” At that time restaurant patrons who wanted mellow light could choose a place such as Sherry’s in New York where wall sconces gave off gentle illumination and candles topped by artistic shades reposed on each table. So private! So French!

Candlelight promised the gentility of an elite dinner party, far removed from loud music, noise, and guests who drank too much. Candles suited the tea room perfectly. Not only did they shed flattering light, they discouraged the rowdy, fun-seeking masses from entering the door. Tea room owners, overwhelmingly WASPs, also liked how candles, as well as lanterns and fireplaces, created a quaint atmosphere that they imagined resembled how their Colonial ancestors lived.

Candlelight promised the gentility of an elite dinner party, far removed from loud music, noise, and guests who drank too much. Candles suited the tea room perfectly. Not only did they shed flattering light, they discouraged the rowdy, fun-seeking masses from entering the door. Tea room owners, overwhelmingly WASPs, also liked how candles, as well as lanterns and fireplaces, created a quaint atmosphere that they imagined resembled how their Colonial ancestors lived.

In Greenwich Village some tea rooms of the 1910s used candles exclusively. The homey Candlestick Tea Room was described as “a little eating place chiefly remarkable for its vegetables and poetesses.” Like other tea rooms lit solely by candles it was undoubtedly atmospheric, but its owners Mrs. Pendington and Mrs. Kunze probably had a more basic reason for using candles. Many of the substandard Village buildings had no electricity. Nonetheless candles did not guarantee respectability. In Chicago, police declared the candle-lit Wind Blew Inn disreputable. A dilapidated, Bohemian student hangout, it had only three candles lighting its two floors.

Outside of Bohemian haunts, though, candles in tea rooms continued to suggest quiet good taste. Alice Foote MacDougall pronounced in her 1929 book The Secret of Successful Restaurants that “Tea time is relaxation time and lights are softened, candles lighted, music plays softly, accompanied by the rippling measure of water falling from our fountains.” She spent the considerable sum of $10,000 a year on candles in her tea rooms. In the 1930s genteel shoppers at Joseph Horne’s in Pittsburgh enjoyed tea and cake by candlelight while listening to organ music in the department store’s tea room.

Outside of Bohemian haunts, though, candles in tea rooms continued to suggest quiet good taste. Alice Foote MacDougall pronounced in her 1929 book The Secret of Successful Restaurants that “Tea time is relaxation time and lights are softened, candles lighted, music plays softly, accompanied by the rippling measure of water falling from our fountains.” She spent the considerable sum of $10,000 a year on candles in her tea rooms. In the 1930s genteel shoppers at Joseph Horne’s in Pittsburgh enjoyed tea and cake by candlelight while listening to organ music in the department store’s tea room.

Today candles are so common in restaurants that they are scarcely noticed, yet as recently as 50 years ago they were considered feminine tools of romantic entrapment. A kind of low-level warfare simmered through the 1950s and early 1960s in which women such as Patricia Murphy of the Candlelight Restaurant in Yonkers announced that wives could save their marriages with candle-lit dinners, while men countered they “liked to see what they were eating.” In 1962 a fire official in Beverly MA said that his ban against candles in restaurants was not motivated by a dislike of dining by candlelight but a need to protect the public from “open flames.” But change was on its way. In the 1970s millions of Americans, male and female, would flock to restaurants where they sipped wine while candles flickered against exposed brick walls.

© Jan Whitaker, 2010

Where could you — once upon a time – enjoy European pastries, cinnamon toast, and ice cream soda while you hugged a teddy bear? Rumpelmayer’s, of course. A very popular rendezvous for pampered New York children after a visit to the zoo or the ballet. I suppose adults could hug the bears too, but Rumpelmayer’s sweetness – its confections, pink walls, and shelves of stuffed toys — might close in on you if you didn’t hold fast to some grown-up habits such as cigarettes and highballs.

Where could you — once upon a time – enjoy European pastries, cinnamon toast, and ice cream soda while you hugged a teddy bear? Rumpelmayer’s, of course. A very popular rendezvous for pampered New York children after a visit to the zoo or the ballet. I suppose adults could hug the bears too, but Rumpelmayer’s sweetness – its confections, pink walls, and shelves of stuffed toys — might close in on you if you didn’t hold fast to some grown-up habits such as cigarettes and highballs. Rumpelmayer’s tea and pastry café began its Manhattan life in 1930 in the new Hotel St. Moritz on the corner of Central Park South and Sixth Avenue. The hotel almost immediately went into foreclosure though it continued in business. Oh, happy day when Repeal commenced in December of 1933 and the St. Moritz announced, “In Rumpelmayer’s, as in the Grill, we will feature a number of bartenders with Perambulating Bars, for serving mixed drinks.” Bars might be everywhere, but Rumpelmayer’s other attractions were not. For decades it provided a jolly spot for children’s birthday parties, lunches, late Sunday breakfasts, and afternoon teas and hot chocolates. It closed around 1998.

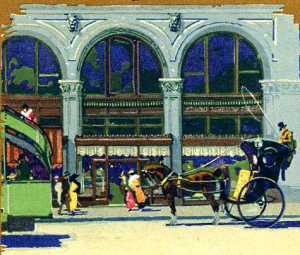

Rumpelmayer’s tea and pastry café began its Manhattan life in 1930 in the new Hotel St. Moritz on the corner of Central Park South and Sixth Avenue. The hotel almost immediately went into foreclosure though it continued in business. Oh, happy day when Repeal commenced in December of 1933 and the St. Moritz announced, “In Rumpelmayer’s, as in the Grill, we will feature a number of bartenders with Perambulating Bars, for serving mixed drinks.” Bars might be everywhere, but Rumpelmayer’s other attractions were not. For decades it provided a jolly spot for children’s birthday parties, lunches, late Sunday breakfasts, and afternoon teas and hot chocolates. It closed around 1998. Always proud of its continental delicacies, New York’s Rumpelmayer’s was related (exactly how I’m not sure) to sister tea shops in London, Paris, and on the Riviera. The original Rumpelmayer’s was begun by an Austrian pastry cook in the German resort town of Baden-Baden in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. It then followed its Russian clientele to Cannes and Nice, then later to Mentone and Monte Carlo. In 1903 a shop was opened on Paris’s Rue de Rivoli (pictured, somewhat later) and in 1907 on St. James Street in London. Parisians, infected by Anglomania in the early 20th century, eagerly adopted the afternoon tea custom, in this case reputedly known as having a feeve o’clock-air at “Rumpie’s.” Though it was rated slightly less chic than the Ritz, it attracted mobs of fashionably dressed women who paraded their outfits up to the counter where, according to custom, they speared their chosen pastries with a fork.

Always proud of its continental delicacies, New York’s Rumpelmayer’s was related (exactly how I’m not sure) to sister tea shops in London, Paris, and on the Riviera. The original Rumpelmayer’s was begun by an Austrian pastry cook in the German resort town of Baden-Baden in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. It then followed its Russian clientele to Cannes and Nice, then later to Mentone and Monte Carlo. In 1903 a shop was opened on Paris’s Rue de Rivoli (pictured, somewhat later) and in 1907 on St. James Street in London. Parisians, infected by Anglomania in the early 20th century, eagerly adopted the afternoon tea custom, in this case reputedly known as having a feeve o’clock-air at “Rumpie’s.” Though it was rated slightly less chic than the Ritz, it attracted mobs of fashionably dressed women who paraded their outfits up to the counter where, according to custom, they speared their chosen pastries with a fork.

In the early 19th century Philadelphians enjoyed driving their carriages to the falls on the Schuykill River, the area now known as East Falls, then lined with hotels and restaurants. Eating places there specialized in a favorite dish associated with Philadelphia long before the advent of cheese steaks, namely catfish and waffles. (I’d like to believe that the dish did not include maple syrup.)

In the early 19th century Philadelphians enjoyed driving their carriages to the falls on the Schuykill River, the area now known as East Falls, then lined with hotels and restaurants. Eating places there specialized in a favorite dish associated with Philadelphia long before the advent of cheese steaks, namely catfish and waffles. (I’d like to believe that the dish did not include maple syrup.) Well into the 20th century waffles were familiar fare in boom towns such as Anchorage, Alaska, and the oilfields of Oklahoma. Around 1915 two young women from Seattle decided to seek their fortune in Alaska with the Two Girls Waffle House (pictured). In what was not much more than a shack with a canvas roof they could handle only eight customers at the counter. But after a year they had made enough money from railroad construction workers to build a permanent structure. A similar success story could be told about the two young men who ran the Kansas City Waffle House in Drumright, Oklahoma, before graduating to a bigger enterprise in Tulsa.

Well into the 20th century waffles were familiar fare in boom towns such as Anchorage, Alaska, and the oilfields of Oklahoma. Around 1915 two young women from Seattle decided to seek their fortune in Alaska with the Two Girls Waffle House (pictured). In what was not much more than a shack with a canvas roof they could handle only eight customers at the counter. But after a year they had made enough money from railroad construction workers to build a permanent structure. A similar success story could be told about the two young men who ran the Kansas City Waffle House in Drumright, Oklahoma, before graduating to a bigger enterprise in Tulsa. Waffles were also a staple of tea rooms in the early 20th century. In places as varied as big city afternoon tea haunts and humble eateries in old New England homesteads, waffles attracted patrons. In 1917 New Yorkers could choose among the

Waffles were also a staple of tea rooms in the early 20th century. In places as varied as big city afternoon tea haunts and humble eateries in old New England homesteads, waffles attracted patrons. In 1917 New Yorkers could choose among the  Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms.

Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms. Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests.

Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests. Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.”

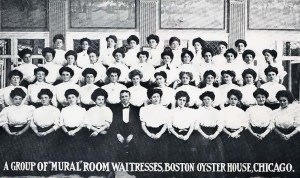

Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.” In 1890 Harry Gordon Selfridge, manager of Field’s in Chicago, took the then-unusual step of persuading a middle-class woman to help with a new project at the store. Her name was Sarah Haring (pictured) and she was the wife of a businessman and a mother. In the parlance of the day, she was needed to recruit “gentlewomen” (= middle-class WASPs) who had “experienced reverses” (= were unexpectedly poor), and knew how to cook “dainty dishes” (= middle-class food) which they were willing to prepare and deliver to the store each day.

In 1890 Harry Gordon Selfridge, manager of Field’s in Chicago, took the then-unusual step of persuading a middle-class woman to help with a new project at the store. Her name was Sarah Haring (pictured) and she was the wife of a businessman and a mother. In the parlance of the day, she was needed to recruit “gentlewomen” (= middle-class WASPs) who had “experienced reverses” (= were unexpectedly poor), and knew how to cook “dainty dishes” (= middle-class food) which they were willing to prepare and deliver to the store each day. And so — despite Marshall Field’s personal dislike of restaurants in dry goods stores — the Selfridge-Haring-gentlewomen team created the first tea room at Marshall Field’s. It began with a limited menu, 15 tables, and 8 waitresses. Sarah Haring’s recruits acquitted themselves well. One, Harriet Tilden Brainard, who initially supplied gingerbread, would go on to build a successful catering business, The Home Delicacies Association. Undoubtedly it was Harriet who introduced one of the tea room’s most popular dishes, Cleveland Creamed Chicken. Meanwhile, Sarah would continue as manager of the store’s tea rooms until 1910, when she opened a restaurant of her own, patenting a restaurant dishwasher in her spare time.

And so — despite Marshall Field’s personal dislike of restaurants in dry goods stores — the Selfridge-Haring-gentlewomen team created the first tea room at Marshall Field’s. It began with a limited menu, 15 tables, and 8 waitresses. Sarah Haring’s recruits acquitted themselves well. One, Harriet Tilden Brainard, who initially supplied gingerbread, would go on to build a successful catering business, The Home Delicacies Association. Undoubtedly it was Harriet who introduced one of the tea room’s most popular dishes, Cleveland Creamed Chicken. Meanwhile, Sarah would continue as manager of the store’s tea rooms until 1910, when she opened a restaurant of her own, patenting a restaurant dishwasher in her spare time.

A graduate of Chicago’s School of Domestic Arts and Sciences named Beatrice Hudson opened the all-male sanctum Men’s Grill (pictured) about 1914 and was responsible for developing a famed corned beef hash which stayed on the menu for 50+ years. Later she would own several restaurants in Los Angeles, coming out of retirement at age 76 to manage the Hollywood Brown Derby and again in her 80s to run The Old World Restaurant in Westwood.

A graduate of Chicago’s School of Domestic Arts and Sciences named Beatrice Hudson opened the all-male sanctum Men’s Grill (pictured) about 1914 and was responsible for developing a famed corned beef hash which stayed on the menu for 50+ years. Later she would own several restaurants in Los Angeles, coming out of retirement at age 76 to manage the Hollywood Brown Derby and again in her 80s to run The Old World Restaurant in Westwood.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.