As some New Yorkers may recall, their city once boasted a certified branch of the famed Maxim’s de Paris. It opened in 1985 on two floors in the Carlton House on Madison and 61st. After seven years in which it went through many changes, it closed in 1992. It was grand and expensive, but despite its golden name never made it into the highest ranks of NYC restaurants.

As some New Yorkers may recall, their city once boasted a certified branch of the famed Maxim’s de Paris. It opened in 1985 on two floors in the Carlton House on Madison and 61st. After seven years in which it went through many changes, it closed in 1992. It was grand and expensive, but despite its golden name never made it into the highest ranks of NYC restaurants.

The proprietor of an earlier, independent Maxim’s in New York, Julius Keller [pictured below], once wrote that “the American people reveled in anything that savored of a European atmosphere,” but perhaps that was truer in his day than the 1980s. His Maxim’s thrived from 1909 until 1920 when it fell victim to wartime austerity.

It was one of the “lobster palaces” on and near Broadway that appeared before the First World War to cater to fun-seeking after-theater crowds. Typically the palaces adopted French names, poured champagne like water, and featured some form of entertainment as well as premium-priced chicken sandwiches and broiled crustaceans.

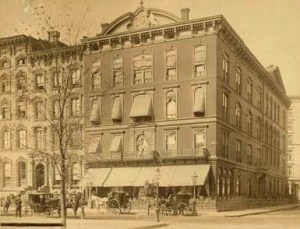

Keller, who liked to be called Jules because it was classier, was a Swiss immigrant who landed in New York solo in 1880 at age 16. After working as a waiter in a number of restaurants and hotels, and eventually owning a few, he found a promising location on 38th street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue. Activity was moving in that direction and he thought he could make a go of it despite the hundreds of thousands of dollars lost by four failed predecessors which included the Café des Ambassadeurs and the Café de France.

Keller, who liked to be called Jules because it was classier, was a Swiss immigrant who landed in New York solo in 1880 at age 16. After working as a waiter in a number of restaurants and hotels, and eventually owning a few, he found a promising location on 38th street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue. Activity was moving in that direction and he thought he could make a go of it despite the hundreds of thousands of dollars lost by four failed predecessors which included the Café des Ambassadeurs and the Café de France.

At first he operated under the name Café de France. Nobody came. So, being resourceful, he dressed his waiters like servants to Louis XIV, hired an orchestra, and, most importantly, borrowed the name of the famous Paris house of good food and naughty gaiety, Maxim’s. Success followed quickly. Each year on New Years Eve he gave away souvenir plates displaying the words, “Let us go to Maxim’s, where fun & frolic beams,” possibly lyrics from the 1899 French play The Girl from Maxim’s.

At first he operated under the name Café de France. Nobody came. So, being resourceful, he dressed his waiters like servants to Louis XIV, hired an orchestra, and, most importantly, borrowed the name of the famous Paris house of good food and naughty gaiety, Maxim’s. Success followed quickly. Each year on New Years Eve he gave away souvenir plates displaying the words, “Let us go to Maxim’s, where fun & frolic beams,” possibly lyrics from the 1899 French play The Girl from Maxim’s.

His clientele was made up of society figures, financiers, celebrities, and those indispensable “others” with money to spend. Maxim’s courtly tone had a tendency to slip occasionally, as was often the case with lobster palaces. On one occasion in 1911, 250 people coming from the annual automobile show jammed the place, causing quite a fracas when the staff had to forcibly eject them in the wee hours. But Keller drew the line at known criminals. He deliberately discouraged the patronage of gangster friends from the old days – when he had ventured into gambling and, as part of the operation of his Old Heidelberg, prostitution. He wanted Maxim’s to be first-class.

During his years operating Maxim’s Jules was known as “the father of café society,” and for providing male dance partners for lone women patrons in the dance craze of 1914. Among these was his discovery, Rudolph Valentino. He was proud of his restaurant. As he wrote in his 1939 autobiography Inns and Outs, his visit to the original Maxim’s convinced him “that the replica we had put together . . . suffered nothing from comparison.”

Given restaurant-world Francophilia and the fame of the Maxim’s name, it’s to be expected that there were namesakes scattered across the U.S.A. (even in pre-WWI Salt Lake City, a city not generally known for kicking up its heels). And it’s hardly surprising that there was yet another Maxim’s in New York, this one sprouting in the Depression among other Greenwich Village hotspots such as The Black Cat, The Blue Horse, and El Chico. Other than that it acquired new banquettes around 1931, I know absolutely nothing about it.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.