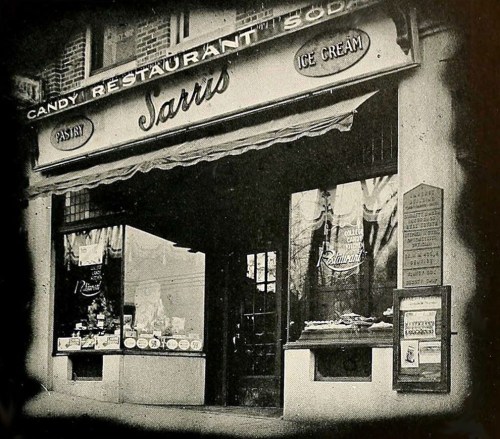

It is always a big deal to me when I find a restaurant proprietor’s memoir, all the more so when he or she conducted an “everyday” sort of restaurant. My Ninety-Five Year Journey, privately published by Charles N. Sarris in 1987, was a just such a wonderful, and rare, find.

The book illustrates a fairly typical restaurant career for thousands of Greek-Americans who opened restaurants in small towns which had few eating places in the early decades of the 20th century.

Charles was born in Lesbos, Greece, in 1891. At 19 he lived in dread that any moment he would be conscripted into the Turkish army and, possibly, spend the rest of his life in an occupied country. He decided to leave for the U.S. For the next six years he bounced around Connecticut and Massachusetts, working in Greek-owned confectioneries where he learned to make candy and ice cream. In 1916 he went to work in a new confectionery in Amherst MA, population 5,500. It wasn’t long before Charles and his partners, who included his brother James, took over the confectionery and expanded it into a lunchroom serving basic fare such as hamburgers and ham and eggs.

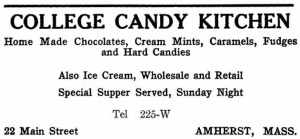

The restaurant was named the College Candy Kitchen [1921 advertisement pictured], obviously aimed at student patrons from Amherst College and the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts). Candy Kitchens run by Greek entrepreneurs could be found throughout the United States in the early 20th century. Coincidentally, another “College Candy Kitchen” did business in Cambridge’s Harvard Square.

The restaurant was named the College Candy Kitchen [1921 advertisement pictured], obviously aimed at student patrons from Amherst College and the Massachusetts Agricultural College (now the University of Massachusetts). Candy Kitchens run by Greek entrepreneurs could be found throughout the United States in the early 20th century. Coincidentally, another “College Candy Kitchen” did business in Cambridge’s Harvard Square.

One of only three Greeks in Amherst when he arrived, Charles would not feel welcome in his new home for some time. He heard racial and ethnic slurs unfamiliar to him from his previous residency in Andover MA. He observed that many townspeople valued people from France, Germany, or England more highly than those from Italy, Poland, the Middle East, or Greece.

In 1927 he and two other merchants who occupied the three-story building located on Main Street across from Amherst town hall formed Amherst Realty Co. to buy the property. Yet not until 1939, after running a thriving restaurant for 23 years, did Charles finally gain admission into one of the town’s fraternal organizations, the Rotary Club.

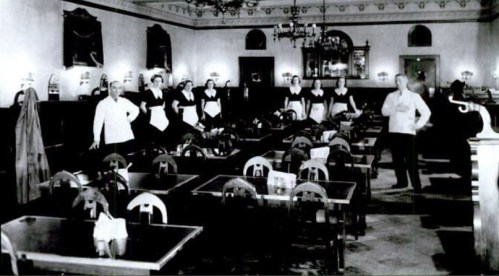

The College Candy Kitchen modernized and expanded in the 1920s [1920s Spanish-style interior shown], despite a disastrous fire in 1928 which necessitated moving to a new location for several months. Business slowed drastically but Charles and James got through the Depression ok.

Students, who made up the bulk of customers, balked when the restaurant introduced new foods such as yogurt and melons. Some greeted watermelon with the objection, “Gee, we’re not Alabama Negroes!” Charles reassured them that the menu would always include staples such as boiled dinners, baked beans, and meatloaf. For decades the restaurant continued to produce its own baked goods, ice cream, and, for holidays, candy.

Once again Charles encountered customer resistance when he hired Afro-Americans as staff or served them as patrons. “We had a lot of opposition from the students but we ignored it,” he wrote. Eventually they settled down and got used to it.

According to Charles, the restaurant closed in 1953 due to illness, parking problems, and customers’ demands for alcoholic beverages (which he did not wish to deal in). It was succeeded by the Town House Restaurant. A 1953 bankruptcy auction notice gave a fair idea of the size of the restaurant then. On the auction block were 30 leather upholstered booths, two circular booths, four showcases, a soda fountain with 12 stools, and kitchen, bakery, and ice cream equipment. I can just picture it.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.