Not all restaurants have been purely, or even mainly, commercial ventures. This was particularly true of women’s suffrage eating places and those of the 1970s feminist movement.

Although the women’s restaurants of these two periods were quite different in some ways, they shared a dedication to furthering women’s causes and giving women spaces of their own in which to eat meals, hold meetings, and in the 1970s, to enjoy music and poetry by women.

In the 1910s most major U.S. cities had at least one suffrage restaurant, tea room, or lunch room sponsored by an organization such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

In the 1910s most major U.S. cities had at least one suffrage restaurant, tea room, or lunch room sponsored by an organization such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

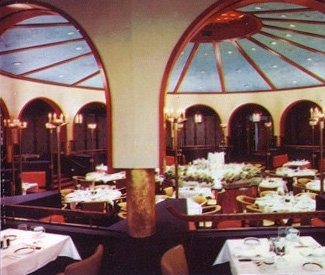

As was true of later feminist restaurants, those of the suffrage era tended to be small and undercapitalized. An exception was the suffrage restaurant financed by the wealthy socialite Alva Belmont in NYC. In terms of patronage, it was almost certainly the most successful women’s restaurant of either era. It reportedly served 900 meals per day from a low-priced menu on which most items were 5 or 10 cents and consisted of soup, fish cakes, baked beans, and home-made pie.

Suffrage restaurants admitted men and welcomed the opportunity to ply them with leaflets and home-made soups, salads, and fritters that would incline them to support the cause. An aged Philadelphia activist recalled in 1988, “I worked at a suffrage tea room. We lured men in, for a good, cheap business lunch. Then you could hand them literature and talk.” In the NYC restaurant operated by NAWSA in 1911, it was impossible to ignore the suffrage issue since every dish, glass, and napkin bore script saying Votes for Women.

Though dedicated to women’s causes, women’s restaurants were not free of conflict. Many suffragists objected to how Alva Belmont ruled with an iron fist, brusquely ordering servers around until they walked out on strike, followed by the dishwashers. Belmont was ridiculed when she brought in her butler and footman to fill the gap. Her footman quit too. Some feminist restaurants experienced discord over cooperative management and, especially, whether or not to serve men.

Though dedicated to women’s causes, women’s restaurants were not free of conflict. Many suffragists objected to how Alva Belmont ruled with an iron fist, brusquely ordering servers around until they walked out on strike, followed by the dishwashers. Belmont was ridiculed when she brought in her butler and footman to fill the gap. Her footman quit too. Some feminist restaurants experienced discord over cooperative management and, especially, whether or not to serve men.

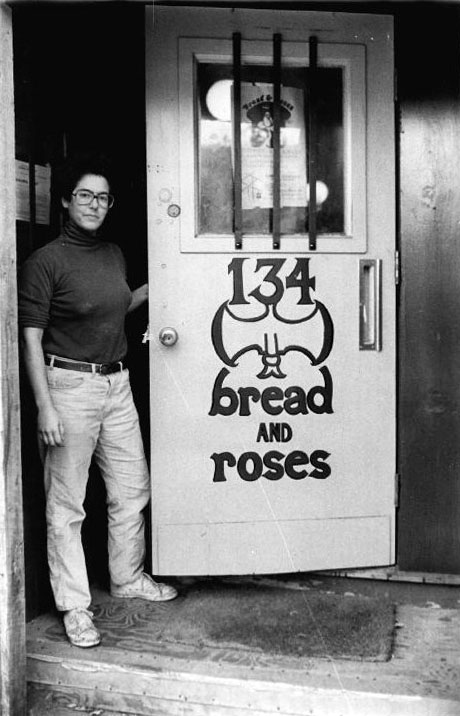

The first feminist restaurant, NYC’s Mother Courage, was founded in April of 1972. (Its co-founder Dolores Alexander discussed it in 2004-2005 interviews.) Others established in the 1970s included Susan B. Restaurant, Chicago; Bread & Roses, Cambridge MA; The Brick Hut, Berkeley CA; Los Angeles Women’s Saloon and Parlor, Hollywood CA; and Bloodroot, Bridgeport CT). Undoubtedly there were more, especially in college towns like Eugene OR and Iowa City IA. In the 1980s a number of women’s coffeehouses appeared, but they were performance spaces more than eating places.

As part of the counterculture, 1970s feminist restaurants typically aimed at a broad set of goals. Women’s equal position in society was paramount but it was embedded in a project of establishing a more peaceful and egalitarian world. Feminist restaurants rotated jobs and paid everyone the same wages. They raised capital by small donations from friends. Staffs were entirely female and women also did most of the renovating. Their decor was spare, with exposed brick walls, mismatched furniture, and chalkboard menus. They served simple peasant-style food, usually prepared from scratch. Some served wine and beer. More often than not menus were vegetarian, or at least beef-less. The L. A. Women’s Saloon and Parlor supported farm workers and would not serve grapes or lettuce. The Brick Hut boycotted Florida orange juice during the anti-gay campaign of spokesperson Anita Bryant. The Women’s Saloon avoided diet plates and sodas, deeming them insulting to large-sized women.

Many proponents of feminist restaurants felt that women were often treated poorly in restaurants, many of which regarded men as their prime customers. Feminist restaurants made a point of presenting women dining with men with the check and wine to sample. But for many women patrons, perhaps especially lesbians, the enjoyment of a non-hostile space was more significant.

At some point each feminist restaurant confronted the touchy question of whether they would serve men. Considerable acrimony erupted around this question at the Susan B. Restaurant in Chicago and Bread & Roses in Cambridge, resulting in the former restaurant’s closure after only a few months. At Bread & Roses a co-founder exercised non-consensus managerial power and fired a server who made men and some heterosexual women feel unwelcome, setting off rounds of group meetings. The restaurant, opened in 1974, was put up for sale and in 1978 became the short-lived “women only” Amaranth restaurant and performance space.

Today Bloodroot may be the sole survivor of the feminist restaurant era.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.