Cities in the United States were generously supplied with saloons before national Prohibition took effect. Saloons occupied some very choice sites, often on corners or other desirable spots. So it was quite a boon for other types of businesses such as drug stores and eating places when those locations became available en masse in 1919.

Cities in the United States were generously supplied with saloons before national Prohibition took effect. Saloons occupied some very choice sites, often on corners or other desirable spots. So it was quite a boon for other types of businesses such as drug stores and eating places when those locations became available en masse in 1919.

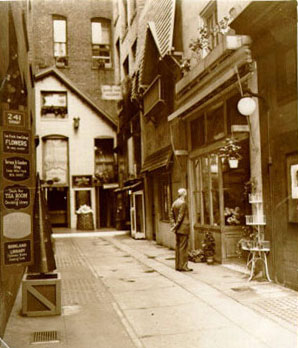

San Francisco’s Temple Bar was an English-style ale house established in the 19th century. Its name played upon London’s Temple Bar – which was a gatehouse, not a drinking place at all. One of its greatest assets was a magnificently carved rosewood and birch backbar said to have been made in Philadelphia in the 1840s. The saloon sat at the end of a quaint little cobblestone alley off Grant Avenue named Tillman Alley or Tillman Place. Just as Prohibition was set to begin, one of its best customers, on a whim perhaps fueled by too many drinks, declared he would buy it; William Davenport, a commercial illustrator who was used to capping off his afternoons there with colleagues from work, paid $300 for the place.

A few months later he and his young wife Hope opened it as the Temple Bar tea room and gift shop. It was also a circulating library which rented books for a small fee. Young Chinese women, dressed in Asian costumes, served lunch and afternoon tea.

William, who was known in artistic circles as “Davvy” and had designed posters for telephone companies up and down the West Coast, decorated the tea room in yellows, blues, and oranges, and fashioned an eye-catching orange sign. To liven up the outside he installed boxwoods in planters. However when they died, victims of the lack of sunlight, he replaced them with modernistic conical-shaped trees he constructed out of painted galvanized iron.

William, who was known in artistic circles as “Davvy” and had designed posters for telephone companies up and down the West Coast, decorated the tea room in yellows, blues, and oranges, and fashioned an eye-catching orange sign. To liven up the outside he installed boxwoods in planters. However when they died, victims of the lack of sunlight, he replaced them with modernistic conical-shaped trees he constructed out of painted galvanized iron.

The alley was inhabited by other interesting businesses and studios such as that of metal craftsman Harry Dixon whose work was exhibited and sold in the Temple Bar gift shop. Another alley denizen was Ye Old Book Shop where George Hargens rapidly gained fame as a seller of rare old books. Grant Avenue was the city’s most fashionable shopping venue in the 1920s, so the Temple Tea Room and its neighbors on Tillman Place were well positioned to catch the attention of affluent shoppers from businesses such as the White House department store just across from the alley.

The alley was inhabited by other interesting businesses and studios such as that of metal craftsman Harry Dixon whose work was exhibited and sold in the Temple Bar gift shop. Another alley denizen was Ye Old Book Shop where George Hargens rapidly gained fame as a seller of rare old books. Grant Avenue was the city’s most fashionable shopping venue in the 1920s, so the Temple Tea Room and its neighbors on Tillman Place were well positioned to catch the attention of affluent shoppers from businesses such as the White House department store just across from the alley.

Hope died in 1932. Davvy carried on the Temple Bar until at least the 1950s when a reporter found him behind the bar mixing dry martinis and old-fashioneds for lunching shoppers. Since his time the location has had many reincarnations as restaurant, bar, and place of entertainment. The backbar was removed to Berkeley in 1990.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

Imagine a restaurant management style diametrically opposed to Gordon Ramsay’s (as he takes command in nightmarish kitchens on TV), and you might well be picturing how Mary Love ran her restaurant, The Maramor in Columbus, Ohio.

Imagine a restaurant management style diametrically opposed to Gordon Ramsay’s (as he takes command in nightmarish kitchens on TV), and you might well be picturing how Mary Love ran her restaurant, The Maramor in Columbus, Ohio. In 1941 Mary described to a home economics conference how she ran her kitchen. She avoided frying and stressed the nutritional properties of food, preparing fresh vegetables to retain flavor and vitamins. Each day her planning department presented the production manager with the day’s menus, while a weighing and measuring specialist prepared trays with complete ingredients for every dish. The trays were given to the cooks, along with detailed instructions for cooking. “This,” Mary said, “helps them to keep their poise and self-respect through the working day, and a cook with poise and self-respect has a better chance of turning out a good product.” (Gordon?)

In 1941 Mary described to a home economics conference how she ran her kitchen. She avoided frying and stressed the nutritional properties of food, preparing fresh vegetables to retain flavor and vitamins. Each day her planning department presented the production manager with the day’s menus, while a weighing and measuring specialist prepared trays with complete ingredients for every dish. The trays were given to the cooks, along with detailed instructions for cooking. “This,” Mary said, “helps them to keep their poise and self-respect through the working day, and a cook with poise and self-respect has a better chance of turning out a good product.” (Gordon?) Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms.

Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms. Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests.

Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests. Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.”

Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.” In 1890 Harry Gordon Selfridge, manager of Field’s in Chicago, took the then-unusual step of persuading a middle-class woman to help with a new project at the store. Her name was Sarah Haring (pictured) and she was the wife of a businessman and a mother. In the parlance of the day, she was needed to recruit “gentlewomen” (= middle-class WASPs) who had “experienced reverses” (= were unexpectedly poor), and knew how to cook “dainty dishes” (= middle-class food) which they were willing to prepare and deliver to the store each day.

In 1890 Harry Gordon Selfridge, manager of Field’s in Chicago, took the then-unusual step of persuading a middle-class woman to help with a new project at the store. Her name was Sarah Haring (pictured) and she was the wife of a businessman and a mother. In the parlance of the day, she was needed to recruit “gentlewomen” (= middle-class WASPs) who had “experienced reverses” (= were unexpectedly poor), and knew how to cook “dainty dishes” (= middle-class food) which they were willing to prepare and deliver to the store each day. And so — despite Marshall Field’s personal dislike of restaurants in dry goods stores — the Selfridge-Haring-gentlewomen team created the first tea room at Marshall Field’s. It began with a limited menu, 15 tables, and 8 waitresses. Sarah Haring’s recruits acquitted themselves well. One, Harriet Tilden Brainard, who initially supplied gingerbread, would go on to build a successful catering business, The Home Delicacies Association. Undoubtedly it was Harriet who introduced one of the tea room’s most popular dishes, Cleveland Creamed Chicken. Meanwhile, Sarah would continue as manager of the store’s tea rooms until 1910, when she opened a restaurant of her own, patenting a restaurant dishwasher in her spare time.

And so — despite Marshall Field’s personal dislike of restaurants in dry goods stores — the Selfridge-Haring-gentlewomen team created the first tea room at Marshall Field’s. It began with a limited menu, 15 tables, and 8 waitresses. Sarah Haring’s recruits acquitted themselves well. One, Harriet Tilden Brainard, who initially supplied gingerbread, would go on to build a successful catering business, The Home Delicacies Association. Undoubtedly it was Harriet who introduced one of the tea room’s most popular dishes, Cleveland Creamed Chicken. Meanwhile, Sarah would continue as manager of the store’s tea rooms until 1910, when she opened a restaurant of her own, patenting a restaurant dishwasher in her spare time.

A graduate of Chicago’s School of Domestic Arts and Sciences named Beatrice Hudson opened the all-male sanctum Men’s Grill (pictured) about 1914 and was responsible for developing a famed corned beef hash which stayed on the menu for 50+ years. Later she would own several restaurants in Los Angeles, coming out of retirement at age 76 to manage the Hollywood Brown Derby and again in her 80s to run The Old World Restaurant in Westwood.

A graduate of Chicago’s School of Domestic Arts and Sciences named Beatrice Hudson opened the all-male sanctum Men’s Grill (pictured) about 1914 and was responsible for developing a famed corned beef hash which stayed on the menu for 50+ years. Later she would own several restaurants in Los Angeles, coming out of retirement at age 76 to manage the Hollywood Brown Derby and again in her 80s to run The Old World Restaurant in Westwood.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.