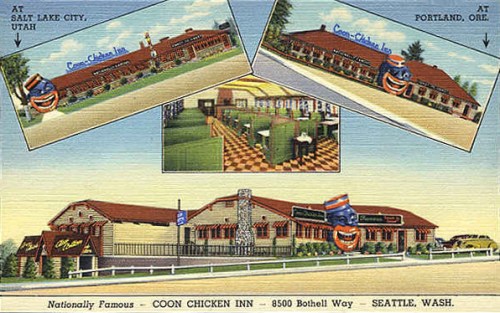

The long-gone Coon Chicken Inn restaurant chain claimed in its advertising that it was “nationally famous.” I believe that was a bit of an exaggeration – then – but it might be true now. Its present-day fame, more accurately its notoriety, is based on its objectionable name and use of a grotesque racist image on buildings, delivery trucks, china, glassware, and printed advertising pieces.

To whatever degree it was nationally famous it can only have been for its racist depictions. Certainly it could not have achieved fame for its food. The menu of the Coon Chicken Inn reveals selections only a few degrees more ambitious than the drive-ins of the 1930s. Other than chicken dinners, the menu included chili, burgers, and ice cream desserts.

Nonetheless, in its time it was a popular chain of four roadhouse restaurants with one each in Salt Lake City (est. 1925), Seattle WA (est. 1929), Portland OR (est. 1930), and Spokane WA. According to one account there were also Coon Chicken Inns in Denver, Los Angeles, and San Francisco but I’ve been unable to find any trace of them.

In 1930 Seattle’s NAACP protested against the restaurant’s racist imagery. Under threat of prosecution the chain’s owners, Maxon Lester Graham and Adelaide Graham, repainted the grotesque black faces on their restaurants’ entryways blue. They also obliterated the words “Coon Chicken Inn” painted on the figures’ teeth.

Having avoided prosecution they changed nothing else, keeping the chain’s name and logo, all of which seemed not to bother the restaurants’ white patrons at all. I would guess most people gave little thought to the large grinning heads, having already accepted the caricatures as merely another instance of the widespread “comical” portrayal of black Americans. They probably also saw them as just another example of an eye-catching building feature employed by roadside restaurants to attract motorists’ attention. Few white people perceived the restaurants as racist.

Having avoided prosecution they changed nothing else, keeping the chain’s name and logo, all of which seemed not to bother the restaurants’ white patrons at all. I would guess most people gave little thought to the large grinning heads, having already accepted the caricatures as merely another instance of the widespread “comical” portrayal of black Americans. They probably also saw them as just another example of an eye-catching building feature employed by roadside restaurants to attract motorists’ attention. Few white people perceived the restaurants as racist.

The Coon Chicken Inns regularly hosted meetings of clubs, civic organizations, and sororities ranging from a Democratic Club to the Junior Hadassah. They were the sites of wedding, anniversary, and birthday parties. In 1942 they were listed in Best Places to Eat, a nationwide guidebook published by the Illinois Auto Club. I can’t help but think that the restaurant in Portland was a peculiarly appropriate location for an Eastern Star group that chose it for their “Poor Taste” party in 1937.

Like the word “mammy” and its stereotyped image, “coon chicken” was supposed to communicate that the restaurant specialized in Southern cuisine, in this case fried chicken. Mammy names and images were widely used by restaurants in the early and middle 20th century. The crudely constructed Mammy’s Cupboard in Natchez MS was another example of roadside “building as sign.” There was a Mammy’s Shanty in Atlanta, Mammy’s Cafeterias in San Antonio TX, and others in the South. Nor was the East without its Mammys: in Atlantic City was Mammy’s Donut Waffle Shop while Brooklyn had Mammy’s Pantry.

Like the word “mammy” and its stereotyped image, “coon chicken” was supposed to communicate that the restaurant specialized in Southern cuisine, in this case fried chicken. Mammy names and images were widely used by restaurants in the early and middle 20th century. The crudely constructed Mammy’s Cupboard in Natchez MS was another example of roadside “building as sign.” There was a Mammy’s Shanty in Atlanta, Mammy’s Cafeterias in San Antonio TX, and others in the South. Nor was the East without its Mammys: in Atlantic City was Mammy’s Donut Waffle Shop while Brooklyn had Mammy’s Pantry.

Several good articles have been published analyzing the Coon Chicken Inn’s everyday racism and the white public’s blithe tolerance of it. I recommend Catherine Roth’s essay for the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project. Because of the volume and quality of what’s been written I hesitated at first to publish this post. I also hate the thought of increasing the desirability of Coon Chicken Inn advertising artifacts. Although there are good reasons to preserve historic racist ephemera, the extreme popularity of these images is disturbing. So great is the demand for them that the marketplace is flooded with fakes, including newly dreamed-up objects that were never used by the chain. Black faces have made a comeback along with “Coon Chicken Inn” on the teeth.

The Portland and Seattle branches of the Coon Chicken Inn closed in 1949 but the Salt Lake City unit remained in business until 1957.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

The Downing family of caterers and restaurateurs, Thomas and his sons George T. and Peter W., were activists in the causes of the abolition of slavery, black suffrage, and black education. They assisted Afro-Americans fleeing slavery before Emancipation as well as those escaping terrorism in the South in the post-Civil War period. Like many free blacks living in cities, they took up the catering trade. Similar to undertaking and barbering, catering was a personal service occupation which offered a degree of opportunity for enterprising people of color.

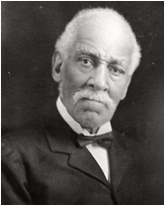

The Downing family of caterers and restaurateurs, Thomas and his sons George T. and Peter W., were activists in the causes of the abolition of slavery, black suffrage, and black education. They assisted Afro-Americans fleeing slavery before Emancipation as well as those escaping terrorism in the South in the post-Civil War period. Like many free blacks living in cities, they took up the catering trade. Similar to undertaking and barbering, catering was a personal service occupation which offered a degree of opportunity for enterprising people of color. Thomas Downing (pictured), the son of freed slaves from Virginia, specialized in oysters. He opened an oyster cellar on Broad Street in New York City in the 1820s, gradually expanding it and earning a fine reputation. Often oyster cellars were “dives” but his was considered first class. He won awards for his pickled oysters which, along with his boned and jellied turkeys, were especially popular at Christmas (see 1856 ad). Over time he owned the Broad Street place and at least one other in NYC and, according to a Rhode Island directory, another in Providence. However, the press seemed always to confuse the various Downings, so it’s possible the latter was under the direction of a son.

Thomas Downing (pictured), the son of freed slaves from Virginia, specialized in oysters. He opened an oyster cellar on Broad Street in New York City in the 1820s, gradually expanding it and earning a fine reputation. Often oyster cellars were “dives” but his was considered first class. He won awards for his pickled oysters which, along with his boned and jellied turkeys, were especially popular at Christmas (see 1856 ad). Over time he owned the Broad Street place and at least one other in NYC and, according to a Rhode Island directory, another in Providence. However, the press seemed always to confuse the various Downings, so it’s possible the latter was under the direction of a son. Thomas’s place on Broad was patronized by men in political and financial circles and he was rumored to have influential connections. Both his sons, George and Peter, had enough pull to win concessions for restaurants in government buildings. Peter ran an eating place in the Customs House in NYC, while George, a friend of MA Senator Charles Sumner, managed one in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. George (pictured) was also well known as the proprietor of a resort hotel, the Sea Girt House, in Newport, Rhode Island.

Thomas’s place on Broad was patronized by men in political and financial circles and he was rumored to have influential connections. Both his sons, George and Peter, had enough pull to win concessions for restaurants in government buildings. Peter ran an eating place in the Customs House in NYC, while George, a friend of MA Senator Charles Sumner, managed one in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. George (pictured) was also well known as the proprietor of a resort hotel, the Sea Girt House, in Newport, Rhode Island. was ignored completely. Or was asked to leave. Or no one took his order. Or was offered a seat in the kitchen. Or his food never arrived. Or it had been adulterated. Or his check was tripled.

was ignored completely. Or was asked to leave. Or no one took his order. Or was offered a seat in the kitchen. Or his food never arrived. Or it had been adulterated. Or his check was tripled. 1964 The Emporia Diner in Virginia admits to having two menus (and that the higher priced one is used “at any time it is felt that business may be adversely affected”) after a black Baltimore woman brings suit saying her family was charged more than three times what whites paid for the same meal.

1964 The Emporia Diner in Virginia admits to having two menus (and that the higher priced one is used “at any time it is felt that business may be adversely affected”) after a black Baltimore woman brings suit saying her family was charged more than three times what whites paid for the same meal.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.