As a Philadelphia Inquirer story observed when the legendary Bookbinder’s on Walnut Street closed for the first time, in 2002, its popular appeal had been based not only on seafood and steaks but also on the restaurant’s ability to play on its history.

Eventually, in the 1940s, the myth led to a claim that it was founded in 1865. Not everyone took the claim seriously, but that still leaves the question of why the restaurant invented it. The motivation was somewhat mysterious considering that Bookbinder’s was in fact very long-lived compared to most restaurants in the U.S., which do well to last five years. It’s curious to me that the actual founding date in the 1890s wasn’t good enough, but it may have been that its actual beginnings didn’t seem like much compared to the long patriotic history of Philadelphia.

An 1895 newspaper story reported that Cecilia Bookbinder, wife of Samuel, had bought the building on 125 Walnut Street for $5,000. Since 1884, it had been operated as an oyster and chop house by a man named Attila Beyer. It appears, however, that the devious Beyer may not have actually owned the building when he sold it to Cecilia, having already used it as collateral for a loan on which he was about to default as he left for California.

Perhaps due to monetary claims by Beyer’s creditors, the Bookbinders evidently lost ownership of the building and didn’t regain it until 1906, nevertheless operating the restaurant all the while, possibly at first under the simple name Merchant Restaurant. The restaurant was in Philadelphia’s long-established insurance district where business people flooded the local eating places at noon.

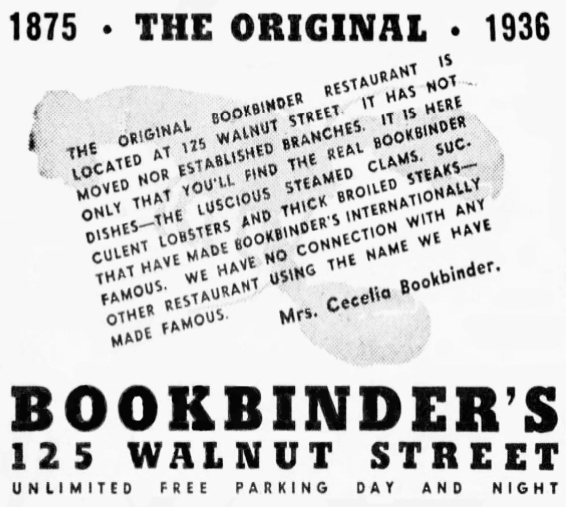

Somewhat before the myth of an 1865 founding was adopted, 1875 was advertised as the restaurant’s start date. For instance that was the date given in a 1940 Life Magazine advertisement for Hines ketchup shown here; it is also indicated by the poster on the wall.

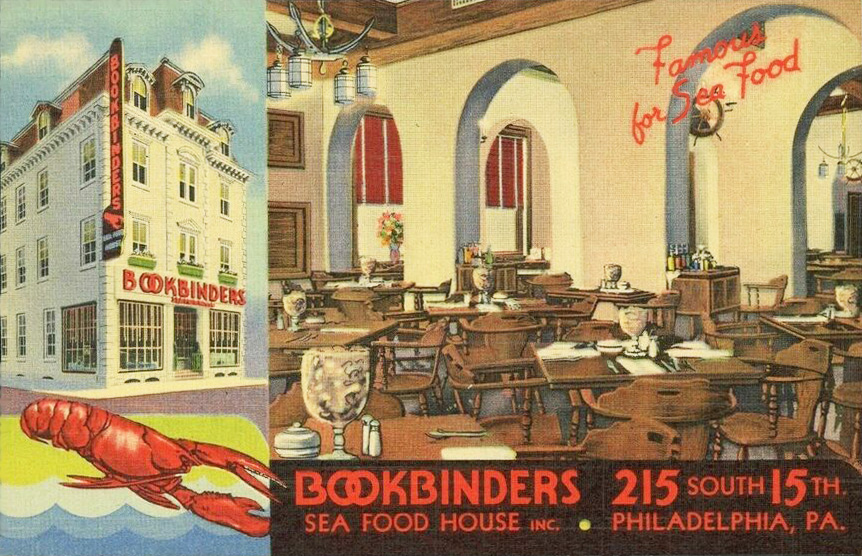

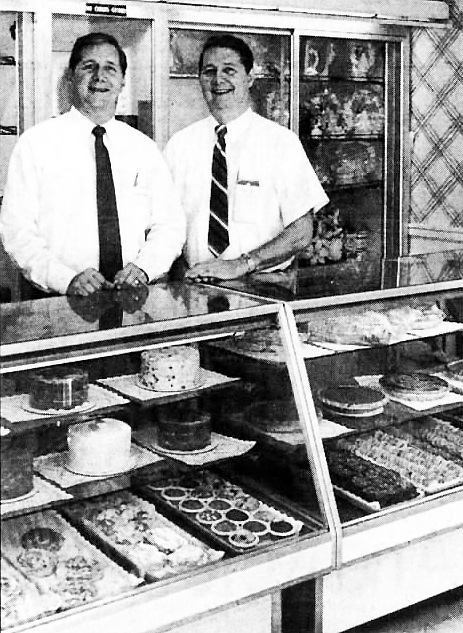

A family rift may partially explain the adoption of an exaggerated founding date. Bookbinder’s on Walnut street adopted the name “Old Original Bookbinder’s” about 1935 or 1936 after Samuel C. Bookbinder, son of the founders, opened a rival Bookbinder’s on South 15th Street [shown above, 1935]. He had been in line to inherit the Walnut Street restaurant but was disinherited upon his conversion from Judaism to Catholicism in order to marry a Catholic woman. The false founding date and the name “Old Original” were likely ways to distance the Walnut Street restaurant from its new competitor. [Note that the 1936 advertisement below had not yet revised the fictitious founding date.]

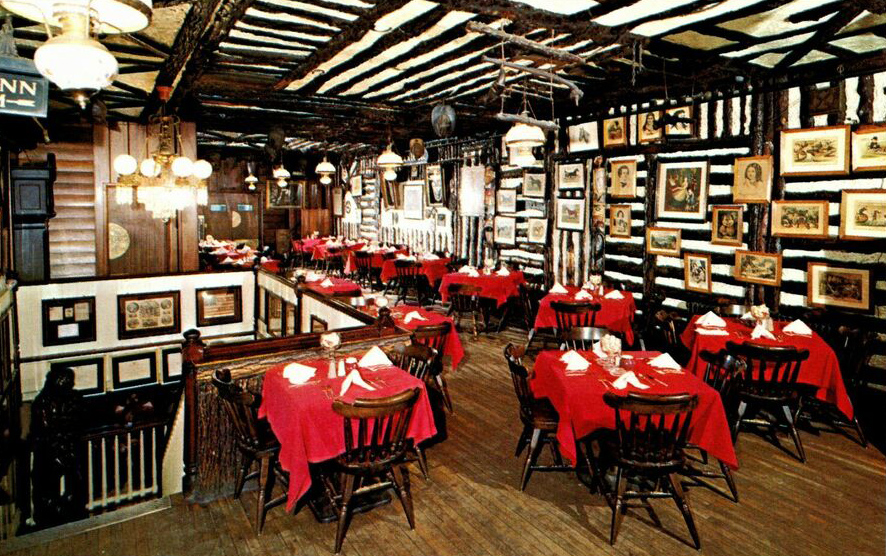

As a result of the family split, Harriet Bookbinder took over the Old Original, operating it with her husband Harmon Blackburn. He was a successful corporate lawyer, and a collector of Americana, including the Lincoln memorabilia, old theater playbills, and Carrier & Ives prints that adorned the restaurant’s walls.

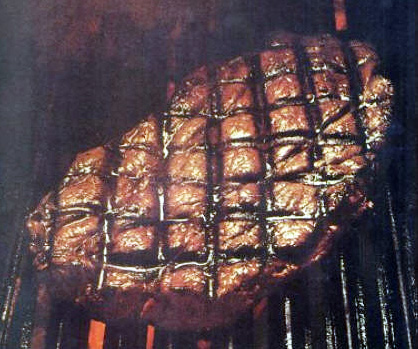

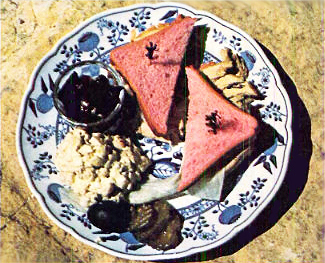

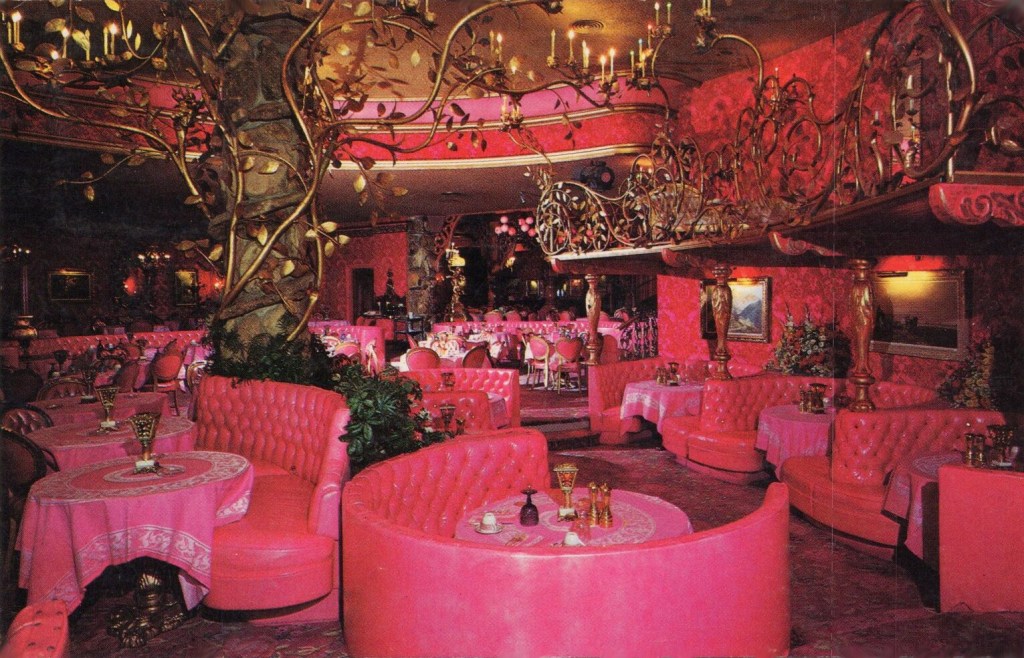

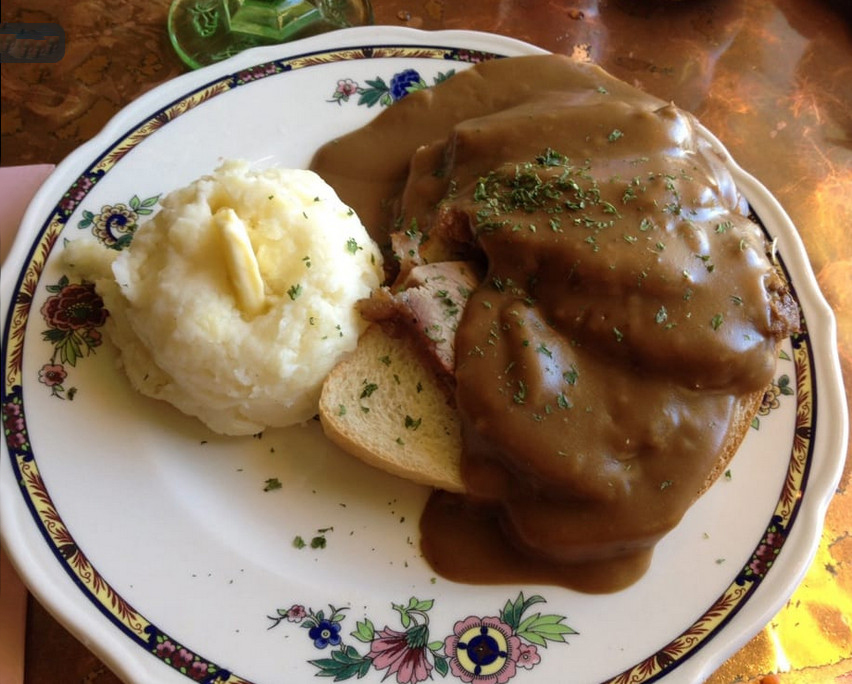

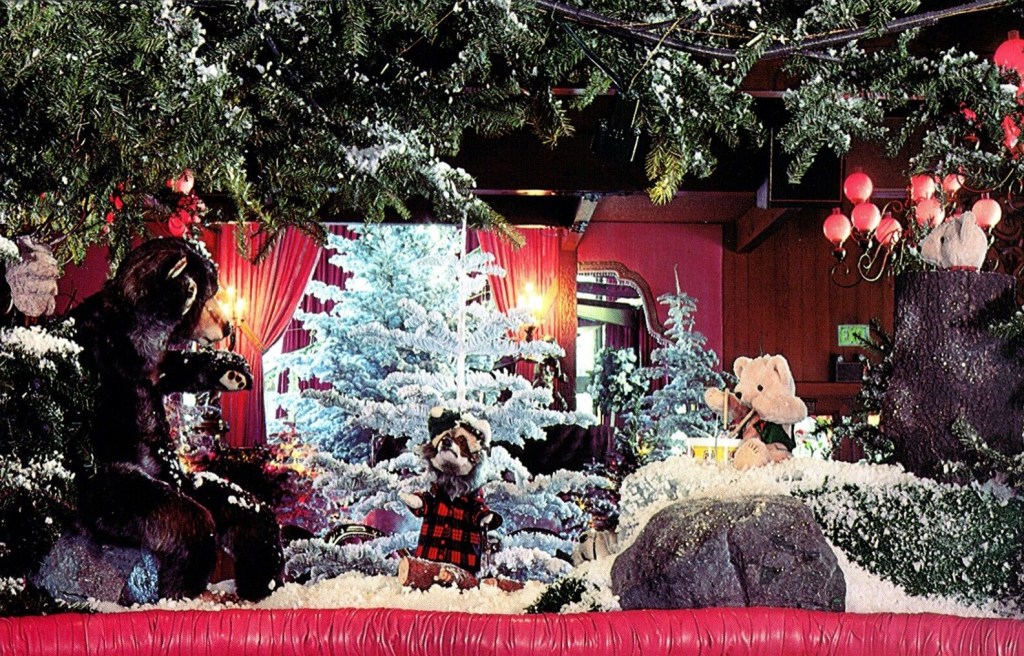

Obviously the building occupied by Old Original Bookbinder’s itself looked aged, and the memorabilia contributed to a sense of age. Other historical attractions were the fireplaces made of old cobblestones taken from Walnut Street. The fireplaces probably dated back to 1915 or 1916 when the city was removing cobblestones from streets. A 1916 advertisement promised “A Beefsteak Dinner in the ‘Maine Woods’” cooked at that room’s fireplace, with steaks and chops grilled in the fireplace and served with oysters, radishes, celery, and hot biscuits baked on the hearth.

When Harriet died in 1944, her husband ran the restaurant for a year and then donated the business to the Federation of Jewish Charities. Along with the building, the furnishings and equipment, the donation included “all food and liquors on hand, the good will and everything in the till.” John and Charles Taxin bought it, with John running it until its final bankruptcy and closure.

In the 1940s and 1950s Old Original Bookbinder’s was regularly recommended in books featuring the country’s favorite restaurants, such as Duncan Hines Adventures in Good Eating. In 1947 “The Dartnell Directory for America’s Most Popular Restaurants named it the country’s most popular eating place of the 2,300 restaurants it recommended.

In 1965 the restaurant celebrated its 100th anniversary as Bookbinder’s — a mere 30 years prematurely.

By the 1970s, the cobblestone fireplaces remained, but some rooms had been redecorated and modernized. Time was catching up with Bookbinder’s then, as new kinds of restaurants with inventive cuisine such as Le Bec-Fin came on the scene. Citing an estimated 300 new restaurants opening in Philadelphia in the early 1970s, a 1978 issue of trade magazine Restaurant Hospitality observed that traditionally conservative Philadelphia was now “vying with New York and San Francisco as the Eating Capital of the United States.”

Nevertheless, in 1986 Restaurant Hospitality rated Old Bookbinders the nation’s 7th highest-grossing restaurant, with annual sales totaling $10.6M and an average dinner check of $33. It was well-known nationwide and particularly popular with tourists, all the more so since it was near historical points of interest.

But nothing lasts forever. Both Bookbinder’s closed in the first decade of the 21st century.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.