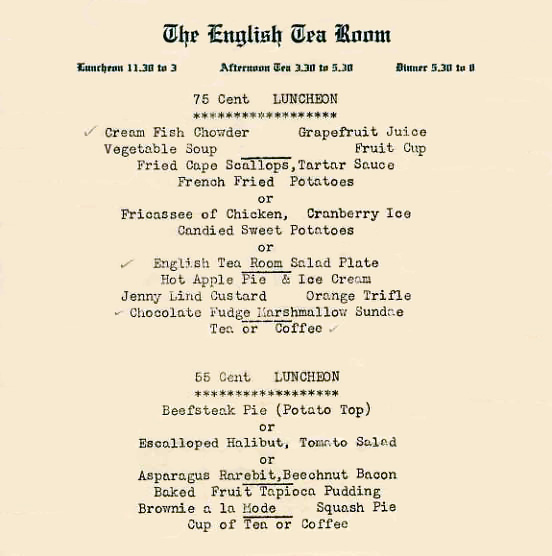

A few years back I published a post called “tableside theater” that looked at cooking performances at guests’ tables in restaurants. This sort of dining room drama occurred mainly in restaurants that wanted to give a sense of luxury that justified a higher price than the meal might otherwise command. [Above: Hotel Bismarck, Chicago]

Another aspect of restaurant theater, usually less dramatic, but also certain to draw attention and oohs and aahs from patrons was the use of carts for ready-to-eat food, usually desserts.

The trend toward tableside food preparation and dessert carts came along mainly after World War II. It is not hard to imagine how restaurant goers then might have longed for normalcy and entertainment.

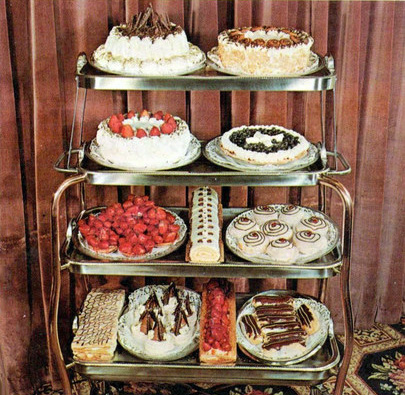

The 1950s is seen as the pinnacle decade of rolling carts of all kinds as well as tableside flambéing. Although carts with ready-to-eat desserts were likely to be found in a wider assortment of restaurants than those that provided tableside preparation, they too delighted guests. And the carts also enabled restaurants to boost demand for desserts. As the back of the postcard shown here notes, “Actual figures show customers buy more high profit desserts when Continental Carts are used to move them.” [The plastic cover of the cart shown above is not very elegant, but it was a practical way of keeping desserts from drying out.]

In Cleveland OH, the Taylor department store, inspired by New York and Europe, introduced rolling carts with salads, cold entrees, and desserts in 1950, in a space that had earlier been a cafeteria. Dessert carts were often used in department store restaurants. Chicago’s Marshall Field’s was not far behind, nor was the restaurant in Oakland CA’s airport. Pastry carts were also used at the Arnoldton, the restaurant in Trenton NJ’s Arnold Constable store.

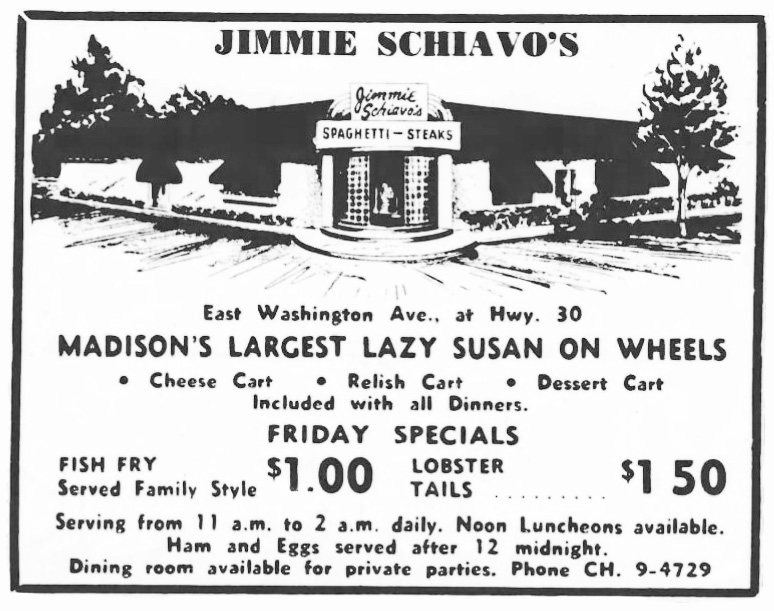

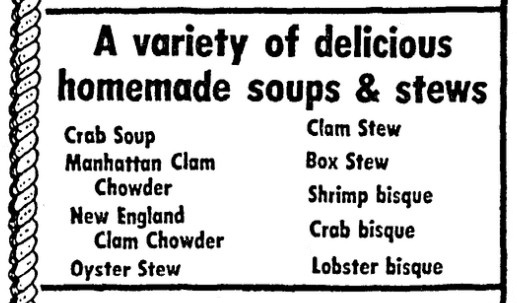

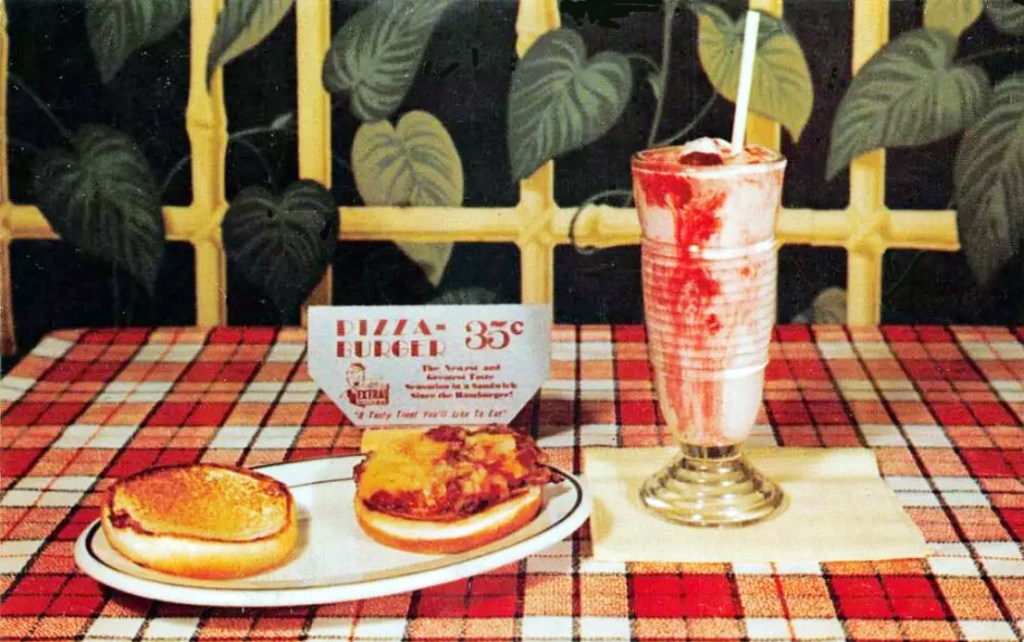

In some restaurants the dessert carts held a variety of after-dinner items including some that are unfamiliar to me. Jimmie Shiavo’s in Madison WI, which had cheese and relish carts in addition to dessert carts, offered desserts such as Italian cookies, a fresh fruit bowl, roasted pumpkin or sunflower seeds, mints, candied fruit, roasted ceci (chickpeas seasoned with spices) and “St. John’s bread” (carob bean pods). St. John’s bread turned up again at Club El Bianco in Chicago, where carts contained olives, St. John’s bread, cheese, peppers, fruits, and nuts, though whether they were all intended as desserts and grouped on the same cart is unclear.

That dessert carts sell more desserts than would otherwise be the case seems to derive from their visual presentation, which is more powerful than a menu description. So it seems strange to me that carts would have items such as seeds, nuts, cheese, or other items such as those at Jimmie Shiavo’s since their appeal is not based on their looks. [The 1947 comic strip above suggests that sometimes carts were for display rather than serving.]

Tableside food presentation did not end in the 1950s, but continued through the 1960s and into the 1990s, though I have the impression it was fading by the late 1980s.

An example of a restaurant that eliminated tableside drama in the 1980s was The Buckingham Inn of Lima OH. Through the 1960s, 1970s, and much of the 1980s it specialized in luxury symbolism. Despite also operating an adjoining place called the Peanut Barrel that offered beer, pizza, and sing-alongs, it appeared to be an old English Inn adorned with knights’ armor and deadly weapons such as a truncheon and a lance. Steaks were the popular fare, but a pastry cart offered chocolate, lemon, and cocoanut cakes three inches high.

In 1986, as the Buckingham Inn’s owner made plans to replace the inn with a more casual family-style restaurant on the site, the pastry cart was auctioned along with the crystal chandeliers.

© Jan Whitaker, 2026

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.