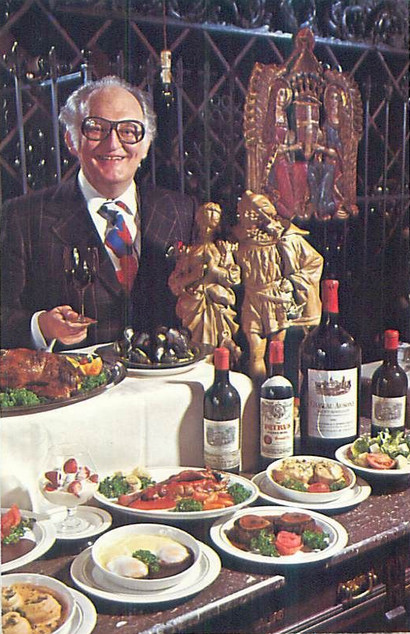

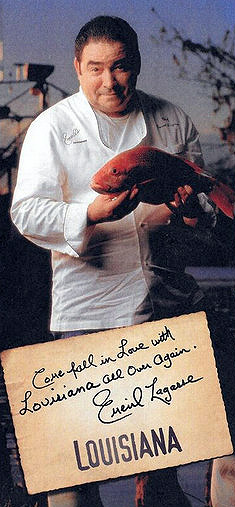

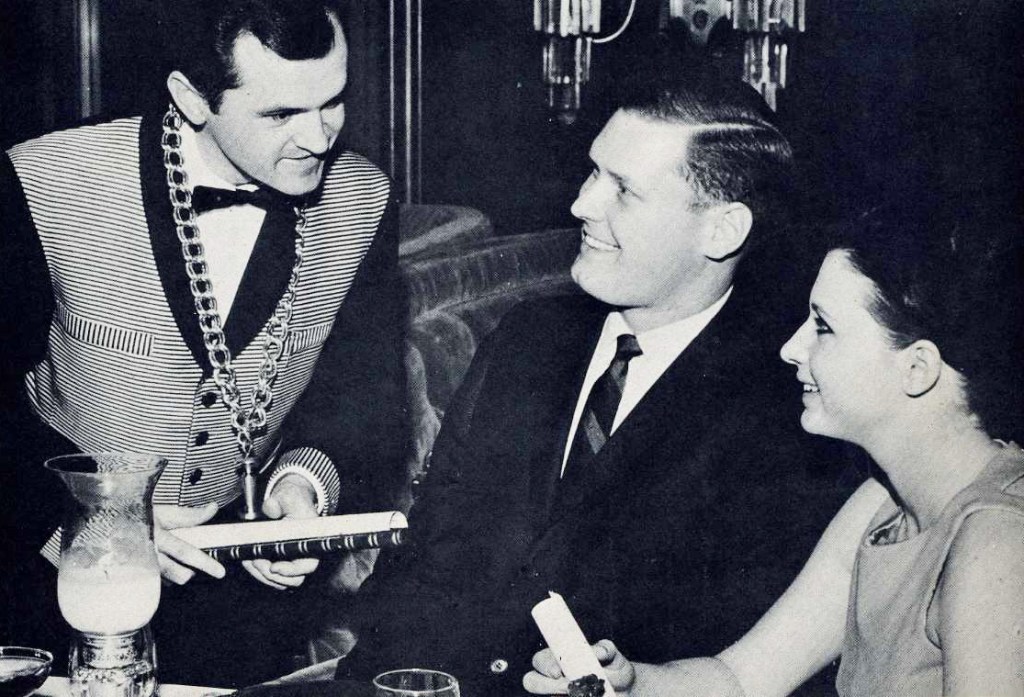

John Spillson came from a restaurant family, so it’s not entirely surprising he went into the business himself, eventually establishing the Café Johnell in Fort Wayne IN in the 1960s and winning endless awards through the years. [Above: ca. 1974]

And yet his path to success was surprising. After working at his father’s restaurant in Fort Wayne, the Berghoff Grill and Gardens, until WWII, he opened his first restaurant in 1951. It was called Meal-A-Minute. I could learn nothing about it other than it went bankrupt the following year.

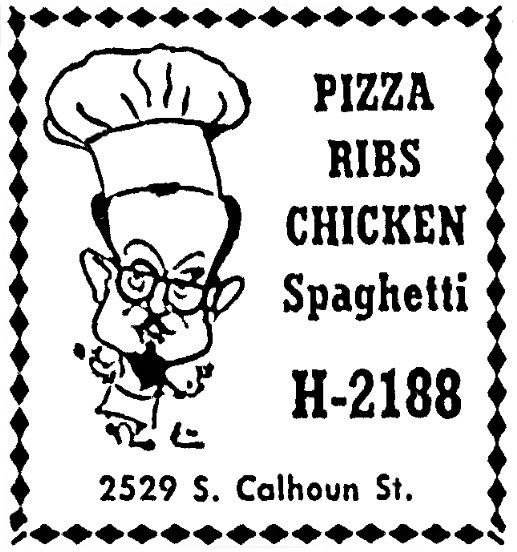

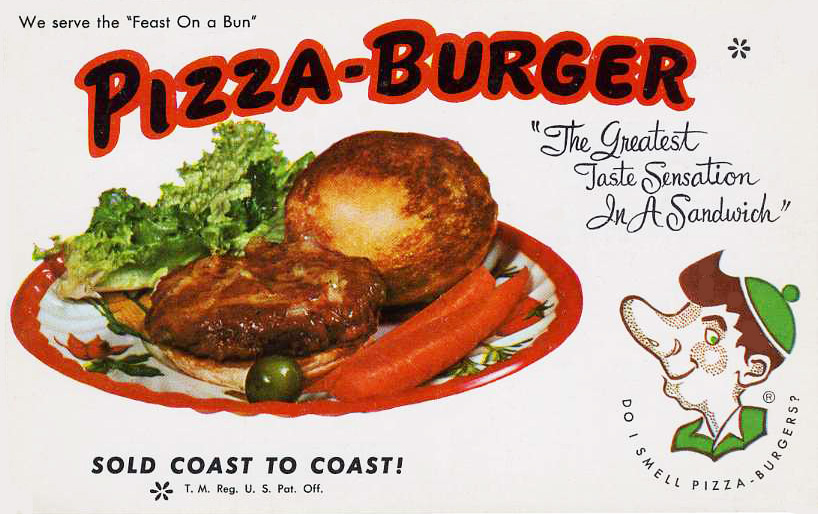

In 1956 he had a new restaurant, Big John’s Pizza on South Calhoun, at the same address that would one day become Café Johnell. (The nickname “Big John” stuck with him for many years, referring to his height and overall size.)

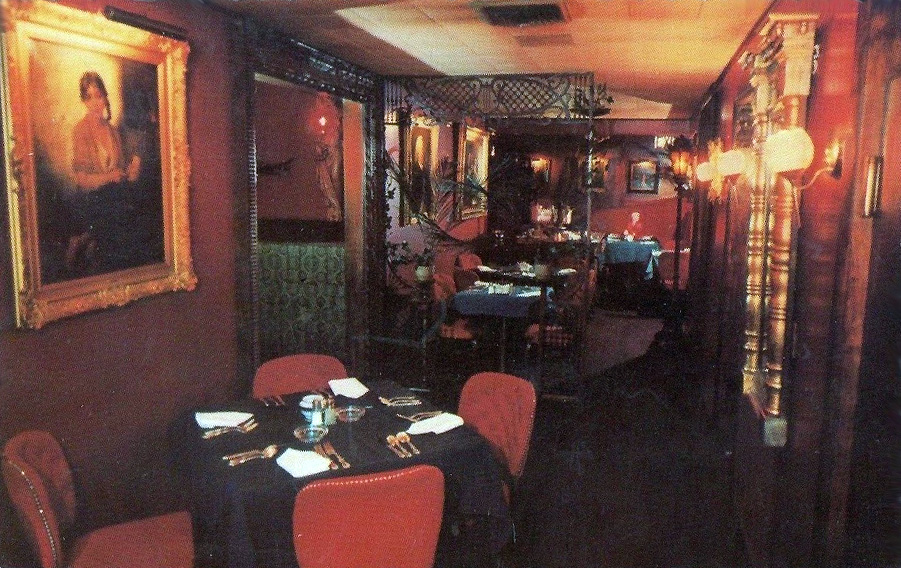

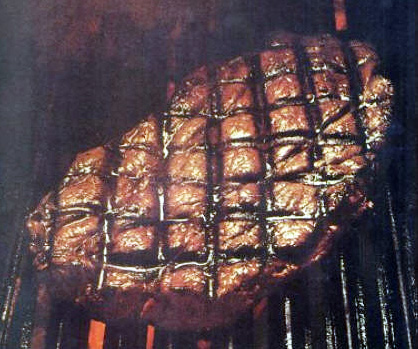

In 1960 John opened a second pizza outlet on North Clinton. Soon he began to transform the South Calhoun pizza place into an Italian coffee house called Café Johnelli. When a local columnist visited it he noted that it served a variety of coffee drinks as well as an unusual lettuce salad, and baklava for dessert. He concluded that dining at Johnelli’s was “new and different” and “a rare treat.” In 1962 the size of the coffee house doubled and a year later John dropped the I from Johnelli.

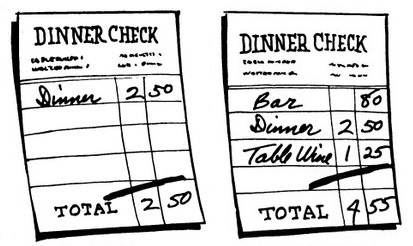

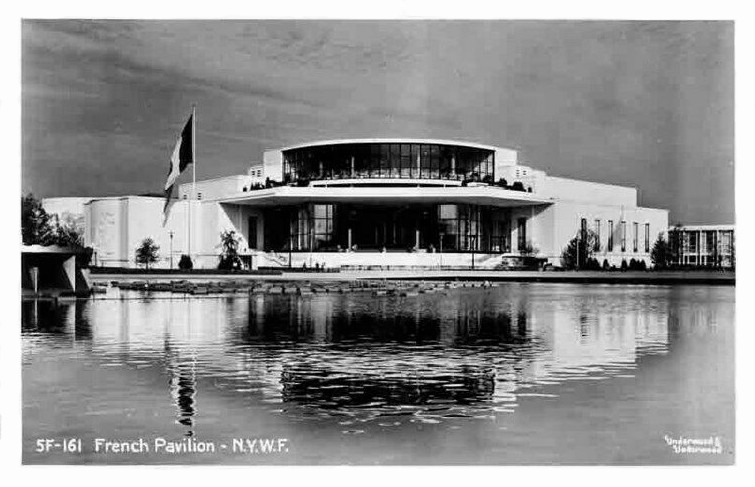

In 1963, he adopted a French identity for the restaurant. As he explained it, “I dropped the Italian food because of the Kennedys. They were serving French food in the White House and wine with dinner. I looked at all the publicity they were getting; the public wanted to do what the Kennedys were doing. . . . So I . . . .decided to go French.”

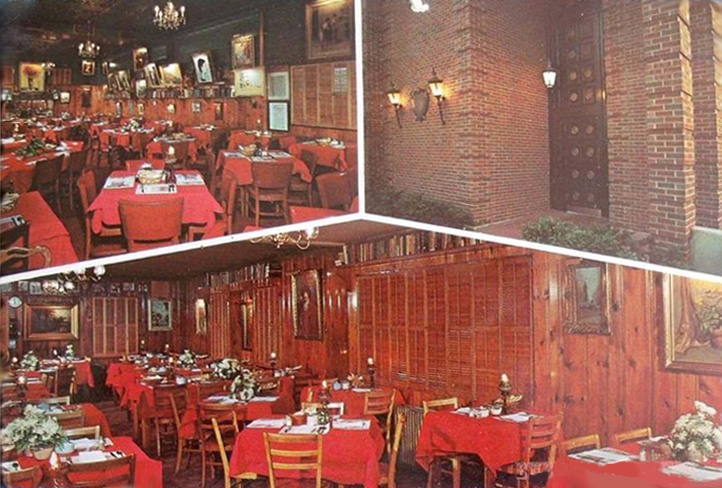

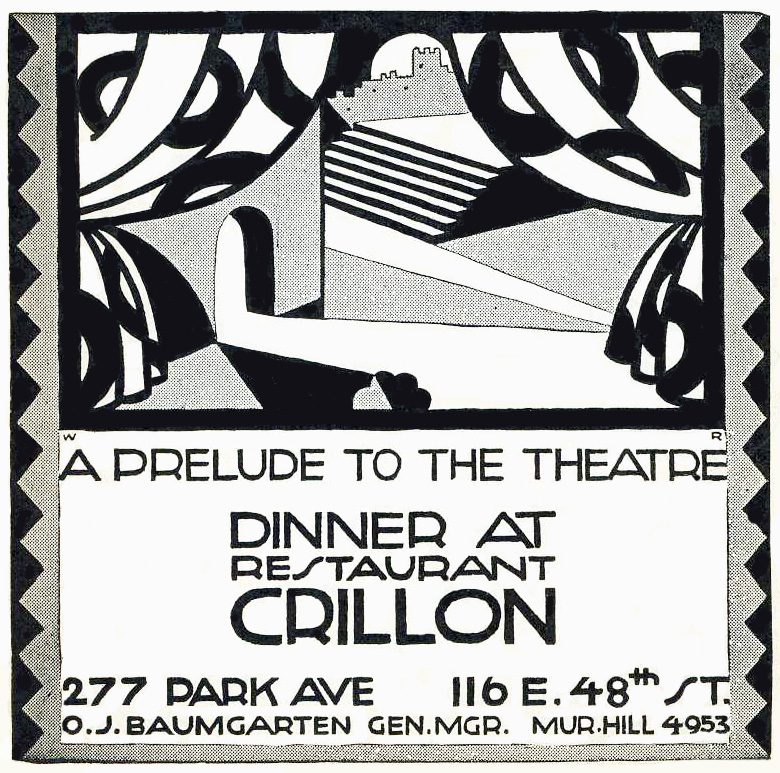

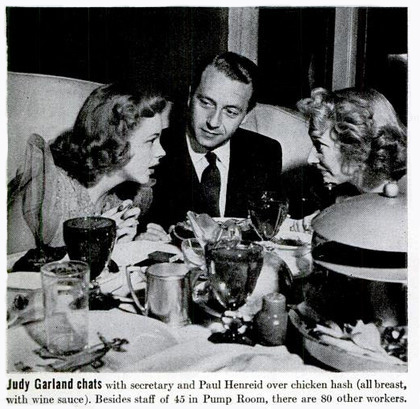

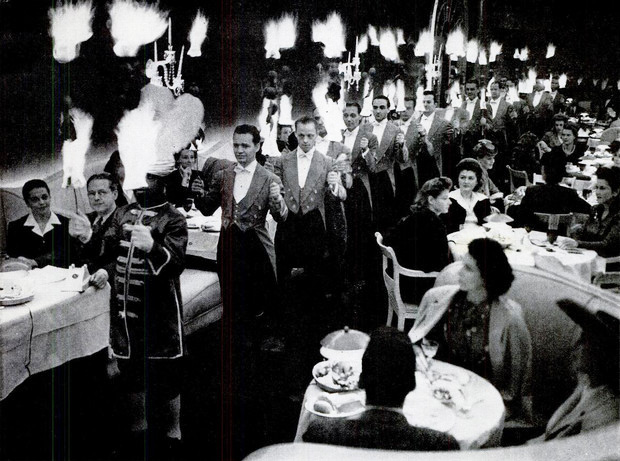

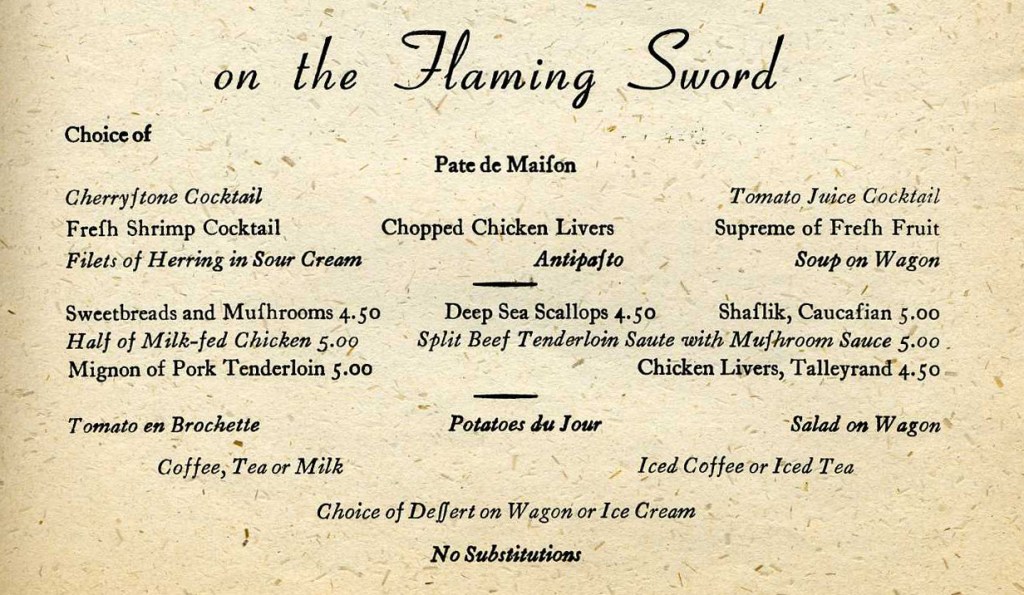

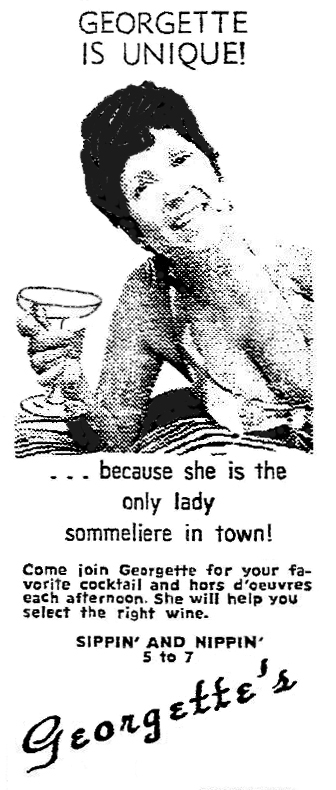

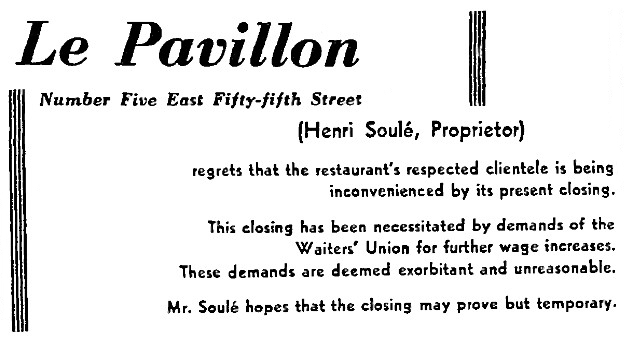

As The Holiday Magazine Award Cookbook noted in 1976, the pizza parlor was “reincarnated . . . as an elegant French restaurant and [he] ran it with such panache that kings, stars of screen and field, everyone within a 200-mile radius who wanted a truly decent meal, flocked to his Café Johnell. Today, in a city noted for auto pistons, life insurance and high school basketball, it’s Spillson’s restaurant that attracts new top executives.” [Above: advertisement from July, 1959, prior to the transformation]

Holiday Magazine awards were some of the almost uncountable number of awards showered on Johnell’s beginning in the 1960s and continuing over the years. They recognized the restaurant’s coffee, wine, and cuisine. But Johnell did not make it into Playboy’s top 25 restaurants in 1984, instead being mentioned as a “regional favorite.”

As John Spillson grew older he brought his daughter Nike into the restaurant as chef, after she was trained in France’s Cordon Bleu. He also began to groom some of his other children for positions as well. Longtime cook Elsie Grant also visited Paris, presumably under John’s sponsorship, trained at the New Haven Culinary Institute, and apprenticed at Le Mistral in New York and Maxim’s in Chicago. Her career was notable in demonstrating opportunities for professionalization rarely offered to Black women cooks in this country.

Following John’s death in 1995 his children continued to run the restaurant until it closed in January, 2001. In its last years the restaurant’s ratings declined, with many feeling the time for a restaurant of that kind had ended decades earlier. Nevertheless, the restaurant reviewer for the Journal-Gazette, who was quite critical of the restaurant’s decor in later years, praised it after it closed even though she admitted it was “a prime example of a business too long on a respirator.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.