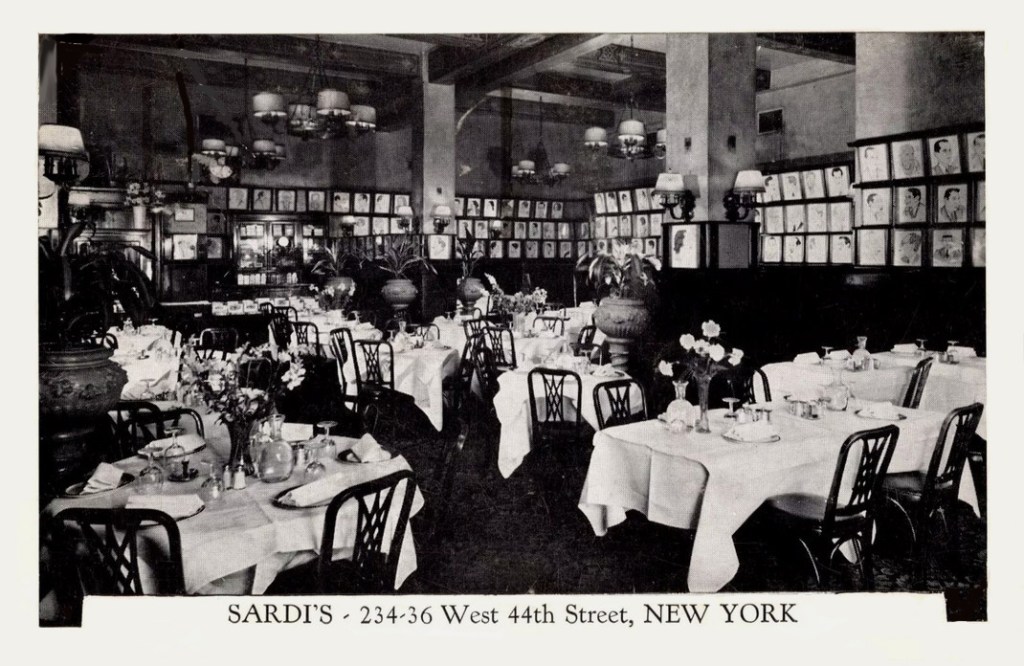

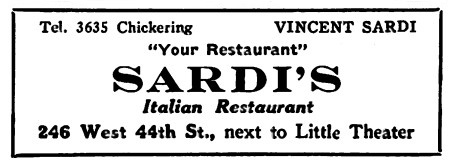

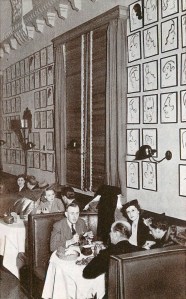

To gather recipes for the Sardi’s cookbook Curtain Up at Sardi’s [1957], co-author Helen Bryson spent two and half weeks, six days each week, in Sardi’s restaurant kitchen. She asked a lot of questions about the food preparation. It was the only way to put together a cookbook, something that she said had never been done before in the restaurant’s long history that dated back to the 1920s. [The restaurant pictured above in the 1950s; below is a 1924 advertisement — “Your Restaurant” is aimed at theater people]

The recipes were intended for use by the public. Whether the restaurant’s chefs ever looked at them is another question. Of course the book’s recipes were adapted for smaller amounts than were normal for the restaurant, and they were no doubt simplified for home cooks too.

And yet the book also includes 26 sauces and dressings, some of them classic French sauces that are far from simple. “Sardi Sauce,” for instance, is made with Sherry wine, light cream, and whipped cream, but also includes Velouté Sauce and Hollandaise Sauce. Velouté Sauce is made with chicken stock and roux (chicken fat and flour). The book also includes a much simpler version, perhaps designed for the homemaker, called Emergency Velouté Sauce (butter, flour, canned broth, and bay leaf).

Later, in contrast to the intricacies of sauce making, comes an amazingly simple recipe for Spaghetti with Tomato Sauce en Chafing Dish which calls for spaghetti, boiling water, salt, tomato sauce (can be canned!) and grated Parmesan. The cook could instead choose to make the book’s Tomato Sauce, but that, by contrast, calls for 11 ingredients including a ham bone. Using that sauce the spaghetti might qualify for a chafing dish but otherwise, I think not.

Mid-century dishes at Sardi’s covered a wide range of cuisines. Italian and French were in the lead, as were favorites of indeterminate origin such as Supreme of Chicken à la Sardi ($1.50 in 1939). But the book also includes hot tamales with chili con carne and turkey chow mein, and even makes room for a few “low-calorie plates,” which were becoming popular in the 1950s.

The recipe for Supreme of Chicken à la Sardi is as follows — minus recipes for the accompanying Duchesse Potatoes and Sardi Sauce. Together, those two components add a major amount of cream to this mid-century “specialty of the house.”

1 cup Duchesse Potatoes

6 slices cooked breast of chicken, heated in sherry wine

12 stalks green-tipped asparagus, canned or cooked

1 cup Sardi Sauce

2 teaspoons grated Parmesan cheese

After being assembled on a serving dish, with the chicken resting on the asparagus, surrounded by piped potatoes and all covered with Sardi Sauce and Parmesan, the dish was to be browned lightly under the broiler.

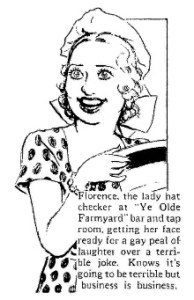

Though Sardi’s food was considered good, the restaurant was not among those that won awards for their cuisine. It is rarely mentioned in “best food” books and articles. Rather, the restaurant’s fame derived from its role as a haven for theatrical people of every kind – actors, agents, producers, publicists, and devoted patrons of live theater. In the early days, Vincent and Eugenia Sardi won over theater people by extending credit to those down on their luck. To the wider public it was most attractive as a site for celebrity spotting and autograph collecting. The restaurant was also well known for years for its canny hat check “girl.”

In the 1963 movie Critic’s Choice Bob Hope plays a critic whose wife, played by Lucille Ball, writes a play which he will need to review. Since it isn’t very good, an honest review would threaten his marriage. [Lucille Ball does not appear in the Sardi’s scene shown above.]

Like the Brown Derby in Los Angeles and the London Chop House in Detroit, Sardi’s decorated its walls with portraits of its celebrity guests – and still does. Some of the older drawings, from the 1920s through the 1950s, have been saved and can be seen by appointment at the NY Public Library.

Until 1947, when Vincent and Eugenia (“Jenny”) Sardi retired and sold the restaurant to their son, Vincent Jr., they divided duties, with Vincent in the dining room greeting guests and Jenny looking over the kitchen and doing the buying. According to one account she was the beloved member of the couple, attracting theatrical guests to the kitchen to visit with her, while Vincent did his duty greeting guests wearing his “guest smile.” A profile in 1939 referred to him as a “chilly individual.” He did, however, give his wife credit for her role in the restaurant’s success. “She does it all,” he said in one interview. [above: the Sardi’s in 1939]

Despite some rocky years and changes in ownership, Sardi’s restaurant, still decorated with celeb faces, continues in business today on W. 44th Street.

A final note: in case anyone was wondering, Sardi’s in New York had no connection with the restaurant of the same name in Los Angeles that opened in the 1930s clearly modeled on the original – a situation that vexed the Sardis.

And thanks to the kind reader who sent me a copy of Curtain Up.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.