There was a time when many Americans considered inexpensive French or Italian restaurants naturally bohemian – wild and crazy, not too clean, filled with oddball characters, and offering menus of unfamiliar and dubious dishes. But nonetheless fascinating. Novelists liked to use them as settings, so they turned up in fiction of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the excerpts below illustrate.

In the final sample presented here we meet up with a restaurant keeper who wishes his place was more bohemian because that would make it a better draw.

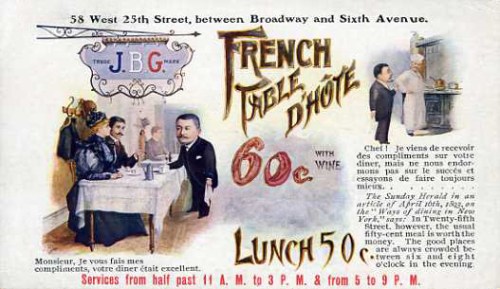

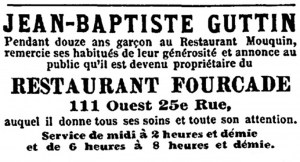

1886 The Midge, Henry C. Bunner – To celebrate the Midge’s 16th birthday, her guardian, a doctor, takes her out to dinner at a table d’hote in New York City’s French quarter.

It was a modest feast, only a plain table-d’hôte dinner, eaten in the heart of the quarter, at a cost of half-a-dollar apiece. They had tried more elaborate dinners, at the great hotels up-town; but they preferred the simpler joys of Charlemagne’s restaurant. They both possessed that element of Bohemianism which belongs to all good fellows; the Midge was a good fellow, as well as the Doctor.

Charlemagne’s is a thing of the past; but he was a jolly king of cheap eating-house keepers while he lasted. He gave a grand and wholesome dinner for fifty cents. The first items were the pot-au-feu and bouilli. If the pot-au-feu was thin, the bouilli was so much the richer. And if the bouilli was something woodeny, why, you had had all the better pot-au-feu before it. Then came an entrée, calves’ brains, perhaps, or the like; a rôti, a vegetable or so coming with it; a good salad, chicory or lettuce or plantain, a dessert of timely fruits, a choice of excellent cheese, and a cup of honest black coffee. And with all this you got bread ad libitum and a half bottle of drinkable wine, that had never paid duty, for it came from California, though it called itself Bordeaux.

1896 Some Modern Heretics: A Novel, Cora Maynard – About two women who adventurously move to Boston to live in a flat and do their own housework. But they don’t know how to cook.

And the alternative of tramping out to restaurants at all hours was a Bohemianism which, in spite of her late advancement, she could not contemplate serenely. It appeared positively disreputable. If her father knew of the actual circumstances of her situation a prompt withdrawal of his original consent would have cut short Vida’s visit on the spot; but she left him in tranquil ignorance . . .

By seven o’clock the girls realized that it was time to have dinner, and then came Vida’s great trial. It was too late to think of cooking anything themselves, so there was nothing to do but face the restaurant.

“Isn’t it a very – a very queer thing to do?” Vida ventured feebly. She would much rather have bought some crackers and eaten them at home in their unpalatable dryness.

“Why, no. It’s a little quiet place we’re going to. I’ve often been. You know we girls don’t believe in being restricted by senseless prejudices. Good gracious, one can’t be so dreadfully hampered in these days of rationality!”

Before long Vida got used to the restaurant, and even enjoyed it when they felt too tired or too lazy to struggle with the cookbook. She enjoyed the whole queer situation and got a taste of such freedom as she had never before dreamed of.

1910 Predestined, Stephen French Whitman – Featuring Benedetto’s, a favorite with artists in New York City.

On the north side of Eighth Street, close to Washington Square, an old, white dwelling-house had been converted into an Italian restaurant, called “Benedetto’s,” where a table d’hôte dinner was served for sixty cents. Some brown-stone steps, flanked by a pair of iron lanterns, gave entrance to a narrow corridor. There, to the right, immediately appeared the dining-room, extending through the house — linoleum underfoot, hat-racks and buffets of oak aligned against the brownish walls, and, everywhere, little tables, each covered with a scanty cloth, set close together.

Felix, at the most inconspicuous table, consumed a soup redeemed from tastelessness by grated parmesan, a sliver of fish and four slices of cucumber, spaghetti, a chicken leg, two cubic inches of ice cream, a fragment of roquefort cheese, and coffee in a small, evidently indestructible cup. Then, through tobacco smoke, he watched the patrons round him, their feet twisted behind chair-legs, their elbows on the table, all arguing with gesticulations. Sometimes, there floated to him such phrases as: “bad color scheme!” “sophomoric treatment!” “miserable drawing!” “no atmosphere!” Benedetto’s was a Bohemian resort.

1912 The Soul of a Tenor, W. J. Henderson – According to a review, “The reader is taken behind the scenes at performances and rehearsals and into the dressing rooms and boudoirs of the artistes; into the café, where foreign singers congregate.”

As for those women who figure in all animated chronicles of the present kind, some of them may have had husbands, but they have tried to forget them, and usually with success. Little Italian restaurants, with hot and opaque atmospheres, are in accord with their temperaments, for their part of the opera world is hot and opaque at all seasons of the year.

It was not a pretty place, that particular Italian restaurant. All the men in it seemed to require cigarette smoke as a condiment for food, and they chewed and puffed alternately. The room was filled with a wreathing blue fog, through which strange head-dresses and still stranger gowns could be seen, for the denizens of this world always garb themselves in streamers of splendor and look not unlike perambulating lamp shades.

They were not only singers. Some were impecunious painters and some were patrons of the arts, who were wont to shout “bravo” from the highest seats in the temple. It gave them a fine satisfaction to eat within reach of real singers. And they were not all Italians, for one feast of spaghetti makes the whole world of Bohemia kin.

1914 Our Mr. Wrenn; The Romantic Adventures of a Gentle Man, Sinclair Lewis – Mr. Wrenn is a lonely lodger who timidly invites a neighbor, Theresa Zapp, to dinner at a restaurant run by Papa Gouroff. She is described as “forward” and “gold-digging.” Although she is not interested in Mr. Wrenn, she accepts his invitation, but fails to be impressed by the restaurant.

The Armenian restaurant is peculiar, for it has foreign food at low prices, and is below Thirtieth Street, yet it has not become Bohemian. Consequently it has no bad music and no crowd of persons from Missouri whose women risk salvation for an evening by smoking cigarettes. Here prosperous Oriental merchants, of mild natures and bandit faces, drink semi-liquid Turkish coffee and discuss rugs and revolutions.

In fact, the place seemed so unartificial that Theresa . . . was bored. And the menu was foreign without being Society viands. It suggested rats’ tails and birds’ nests, she was quite sure. She would gladly have experimented with pate de foie gras or alligator-pears, but what social prestige was there to be gained at the factory by remarking that she “always did like pahklava”?

Papa Gouroff was a Russian Jew who had been a police spy in Poland and a hotel proprietor in Mogador, where he called himself Turkish and married a renegade Armenian. . . . He hoped that the place would degenerate into a Bohemian restaurant where liberal clergymen would think they were slumming, and barbers would think they were entering society, so he always wore a fez and talked bad Arabic. He was local color, atmosphere, Bohemian flavor.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.