Ask someone to name a designer of menu covers and it’s likely you will get a blank look. Although many stylish and eye-catching menus have been produced over time, their designers and illustrators mostly worked in anonymity.

In the early 20th century many of the menu cover artists were probably women. In 1900 the Kalo Shop in Chicago, for instance, employed six women graduates of the Art Institute who were trained in the esthetics of the arts-and-crafts movement. They created menu and magazine covers and other items. It’s likely that most of their menu work was for private banquets, while their biggest clients would have been steamships and railroads.

Individually produced menus such those from the Kalo Shop were rapidly being made obsolete by chromo-lithographers who could achieve quality effects at a lower cost. Unsurprisingly, the next chapter of menu production was taken over by printing companies with designers on their staffs. Some of the printing companies, such as Denver’s Standard Menu Co., were specialists in menu production as early as 1920. Like the women artists of earlier times, the names of designers in printers’ art departments are unknown. In more recent years, menu covers for well-capitalized restaurants have been designed by independent design firms. They created striking logos to be used on signs and menus and in advertising, giving individual restaurants and chains a thoroughly integrated visual signature.

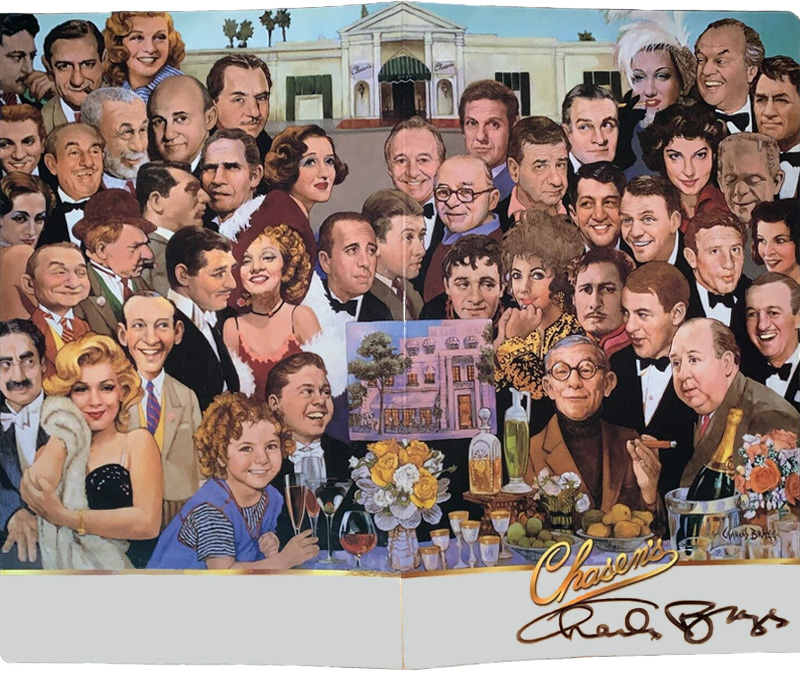

In his book on menu design, “May I take Your Order?,” Jim Heimann says that well known illustrators such as Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell rarely, or never, designed menus or created art specifically for menu covers. That is mostly true, with a few exceptions, such as Al Hirschfeld, who contributed caricatures to New York’s Stage Deli menu and Charles Bragg, who painted a crowd of Hollywood celebrities for Chasen’s in Los Angeles [shown at top].

Chicago’s Blackhawk Restaurant used 8 drawings by Ludwig Bemelmans in the 1960s. They were not originally created for the restaurant, though owner Don Roth bought the originals, obtained Bemelmans’ permission to use them on menus, and gave them to customers as souvenirs.

Here are a few menus with designs that I particularly like.

Café des Beaux Arts, New York City, ca. 1910

A fashionable café of the early 20th century created by brothers Louis Andre and Jacques Bustanoby. Said to be a hangout of the artistic crowd, on Sunday nights it was so crowded no one could enter. Unlike other so-called “lobster palaces,” it reputedly served good food. It closed in 1920, a victim of Prohibition.

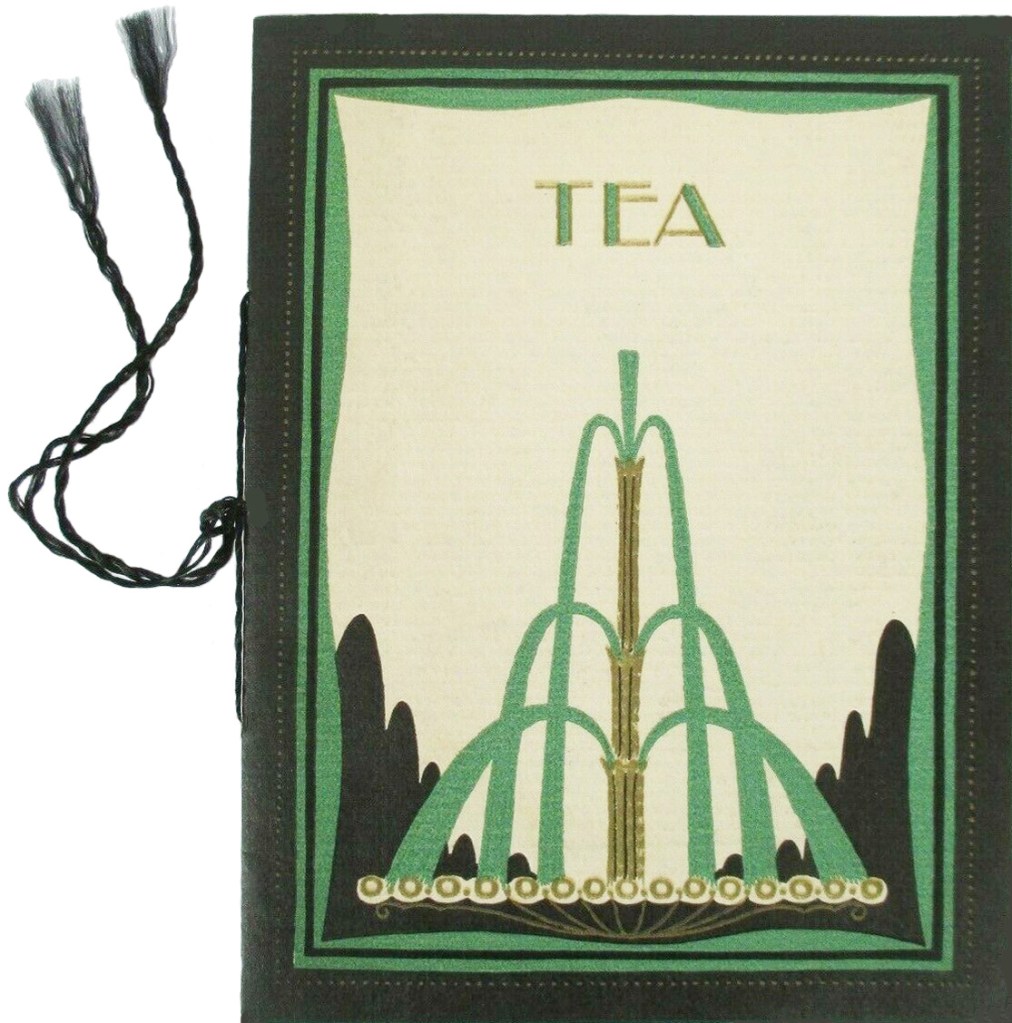

Carson Pirie Scott Tea Room, Chicago, early 20th century

In 1904 the old dry goods store named Carson Pirie Scott bought a building on Chicago’s State Street built by famed architect Louis Sullivan. The 8th-floor tea room soon became a city-wide attraction. This menu of uncertain date has the subdued but assured look of a pedigreed eating place meant to appeal to “ladies” who seek to be correct as well as stylish.

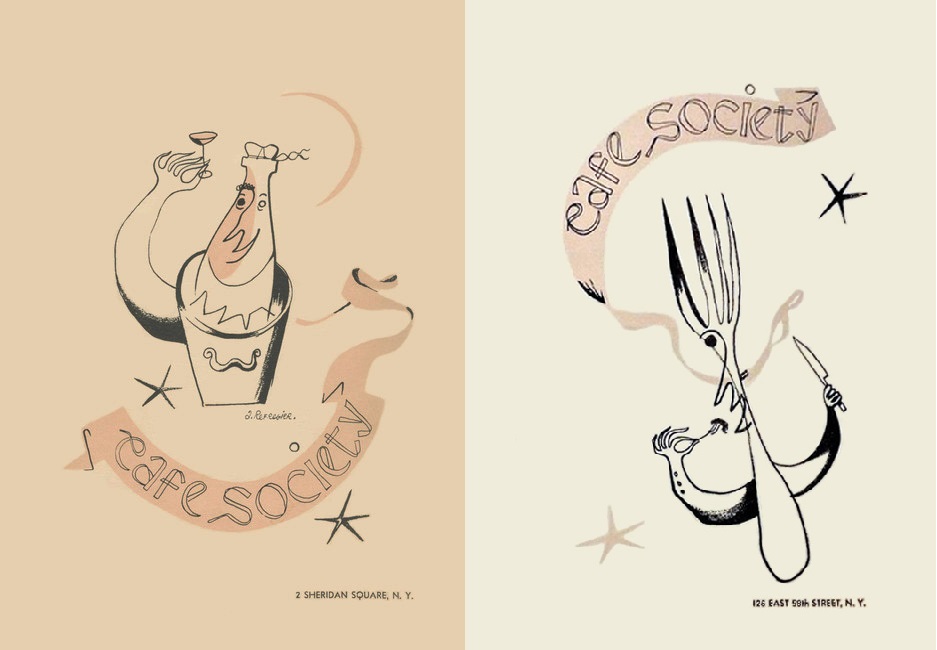

Café Society, New York City, 1938, 1940

In this case a known artist, Anton Refregier, not only contributed his artwork but did so in a full cover design when Barney Josephson, owner of New York’s Café Society music club restaurants, hired him to create menu covers for his two locations, first downtown at Sheridan Square in 1938, and then uptown at East 58th street in 1940. [Both covers are probably on beige-ish, not white, paper]

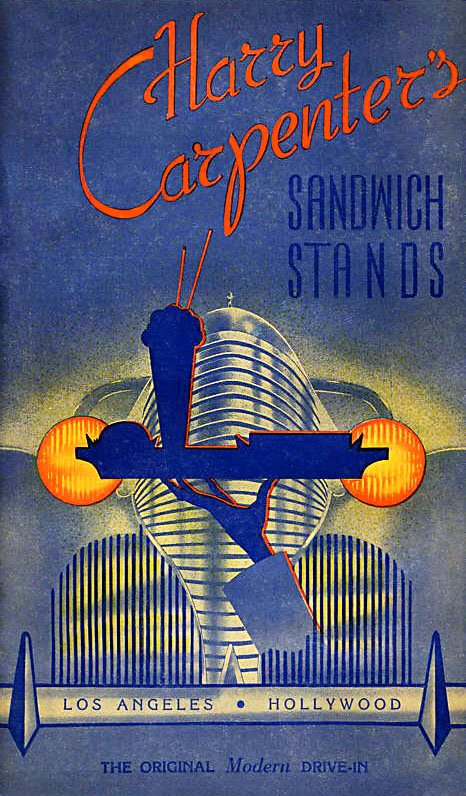

Harry Carpenter’s drive-in, Los Angeles, early 1940s

Harry Carpenter opened his first drive-in, an octagonal building, on the corner of Wilshire Blvd. and Western Ave. It was so popular he soon opened two more. In addition to hamburgers and hot dogs, Carpenter’s served corned beef on rye and chicken a la king on toast. This menu, though somehow foreboding, is dramatic.

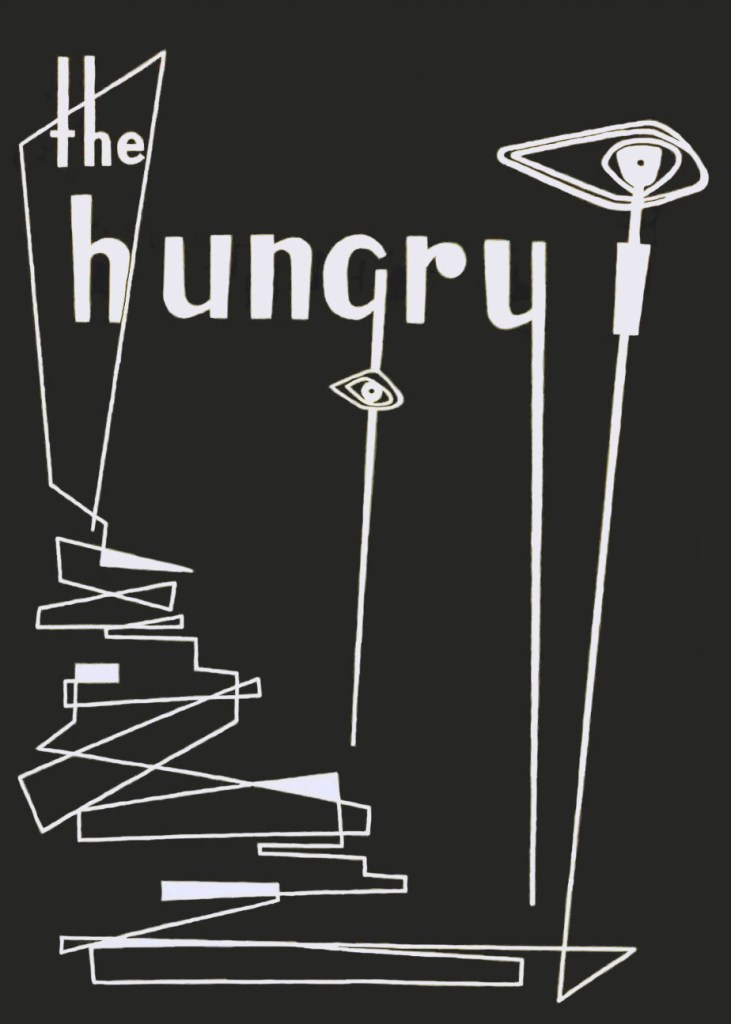

The Hungry I, San Francisco, ca. 1955

The Hungry I, a comedy and music club, was founded around 1950, then sold and relocated to 599 Jackson street in 1954 where this menu was in use. Among those appearing there were Mort Sahl and The Kingston Trio. This menu offers entrees such as steak, lamb chops, chicken, and shish kabob. In ways that are hard to pinpoint, the cover design captures the spirit of the 1950s beatnik counterculture.

Huddle Restaurants, Southern California, 1956

The Huddle’s menu borrows the lettering of the chain’s exterior signage as well as the style of its architecture by Louis Armét and Eldon Davis. Probably their firm also handled the design of this menu, either in-house or by commission. Not all the restaurants in the chain featured futuristic “googie” design, but you can view images of many of those that did.

According to Heimann, the golden age of menu cover design in America ran from the 1920s through the 1950s. The 1960s in his judgement was mostly “a monotonous era” for menu design. Sadly, to me, in recent years printed menus with covers have almost completely vanished, along with postcards, matchbooks, and business cards. Digital photographs, if preserved, may become the sole visual record of most restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

Note: Fans of menu cover art would enjoy Menu Design in America (2011) and May I Take Your Order (1998). Reproductions of menus suitable for framing are available from Cool Culinaria, which also provides links to samples from the collections of Lou Greenstein, Henry Voigt, and the Culinary Institute of America. Also, beginning April 25, over 200 menus from the 19th and 20th centuries selected from Henry Voigt’s collection will be on display at New York’s Grolier Club. More about that later.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.