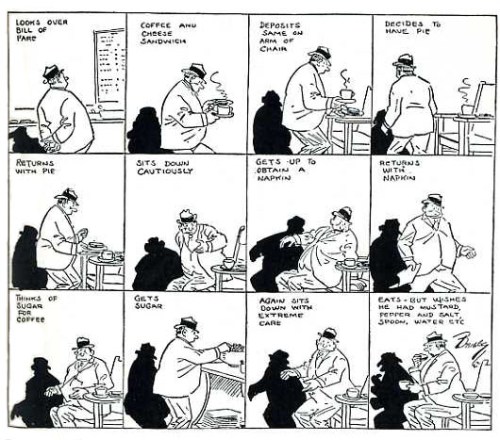

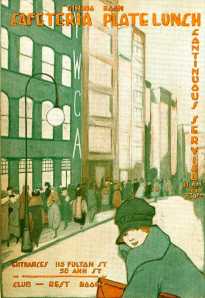

The wooden one-arm chair was a characteristic feature of the “quick lunch” type of eating place which became the popular choice for businessmen around the turn of the last century. The chairs were unattractive and uncomfortable as the cartoon below depicts. But considering that prior to their introduction patrons seeking a speedy lunch often ate while standing at a counter, they offered relative luxury. Solitary seating made sense in a café where businesspeople usually came in alone and spent little more than 10 or 15 minutes at their meal before rushing back to the office or store. (Later, in fact, more attractive one-arm chairs were used in Lord & Taylor Bird Cage restaurants.)

As is true of the fast food restaurants of today, one function of uncomfortable seats in the quick lunch eatery was to discourage lingering. These restaurants were usually shoe-horned into tight quarters in high-traffic, high-rent business centers, so it was paramount that each chair turned customers rapidly. The one-arm chair was patented by a Vermonter named James Whitcomb who designed fixtures for the Baltimore Dairy Lunch and also manufactured portable typewriters.

The core cuisine of the one-arms, and quick lunches in general, consisted of coffee and pie, supplemented by sandwiches and doughnuts. Some of the big one-arm concerns were the Chicago-based companies of John R. Thompson and Charles Weeghman, and the Baltimore Lunch and the Waldorf System, both of which originated in Springfield MA. The companies eventually broadened their menus to include hot dishes, supplying their locations in each city from central commissaries. Though the chains kept prices low, Waldorf prided itself on grating lemons for lemon pies and avoiding manufactured pie fillings, powdered milk, dried eggs and other cost-cutting ingredients developed for the military in World War I and widely used by chains in the 1920s.

Under the intense competition of the late 1920s and the depression, the Lunches replaced their one-arm chairs with tables and chairs and abandoned their utilitarian decor in favor of more colorful interiors in hopes of attracting more women.

© Jan Whitaker, 2008

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.