It is the dawn of the modern era of restaurant-ing. Patronage grows at a rate faster than population increases and the number of restaurant keepers swells by 75% during the decade. Leading restaurant cities are NYC, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco, and Boston. Inexpensive lunch rooms with simple menus and quick service proliferate to serve growing ranks of urban white collar workers, both male and female. Women patronize places they once dared not enter, climbing onto lunch counter stools and venturing into cafes in the evening without escorts.

It is the dawn of the modern era of restaurant-ing. Patronage grows at a rate faster than population increases and the number of restaurant keepers swells by 75% during the decade. Leading restaurant cities are NYC, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco, and Boston. Inexpensive lunch rooms with simple menus and quick service proliferate to serve growing ranks of urban white collar workers, both male and female. Women patronize places they once dared not enter, climbing onto lunch counter stools and venturing into cafes in the evening without escorts.

Diners worry about food safety and cleanliness. Cities mandate restaurant inspections. Meat preservatives used by some restaurants to “embalm” meat that has spoiled come under attack. Restaurants install sanitary white tile on floors and walls to demonstrate cleanliness.

Cooks and waiters unionize. Restaurant owners follow suit, advocating the abolition of the saloon’s “free lunch,” combating strikes, and targeting immigrants who operate “holes in the wall.” As Italians and Greeks open eating places some native-born Americans complain that foreigners are taking over the restaurant business.

New types of eating places become popular such as cafeterias, vegetarian cafés, German rathskellers, tea rooms, and Chinese and Italian restaurants. Dining for entertainment spreads. Adventurous young bohemians seek out small ethnic restaurants (“table d’hotes”) which serve free carafes of wine. Many restaurants introduce live music. The super-rich are accused of “reckless extravagance” as they stage elaborate banquets. The merely well-to-do hire chauffeurs to drive them to quaint dining spots in the countryside.

New types of eating places become popular such as cafeterias, vegetarian cafés, German rathskellers, tea rooms, and Chinese and Italian restaurants. Dining for entertainment spreads. Adventurous young bohemians seek out small ethnic restaurants (“table d’hotes”) which serve free carafes of wine. Many restaurants introduce live music. The super-rich are accused of “reckless extravagance” as they stage elaborate banquets. The merely well-to-do hire chauffeurs to drive them to quaint dining spots in the countryside.

Highlights

1901 As restaurant patronage rises “foody talk” is everywhere. A journalist overhears people “shamelessly discussing the quantity and quality of food which may be obtained for a given price at the various restaurants.” Hobbyists begin collecting menus and Frances “Frank” E. Buttolph deposits over 9,000 menus in the NY Public Library.

1902 Restaurants automate and eliminate waiters. In Niagara Falls a restaurant devises a system of 500 small cable cars which deliver orders to guests. The Automat opens in Philadelphia, inspiring the city’s Dumont’s Minstrels to create a vaudeville act called The Automatic Restaurant which features “Laughing Pie” and “Screaming Pudding.”

1903 “Where and How to Dine in New York” lists restaurants with cellars where men’s clubs play cavemen and eat steak with their hands. – Hawaiians croon in San Francisco restaurants; ragtime bands play in NYC’s Hungarian cafés; and at McDonald’s (“a touch of Bohemia right in the heart of Boston”) a “Young Ladies’ Orchestra” serenades patrons.

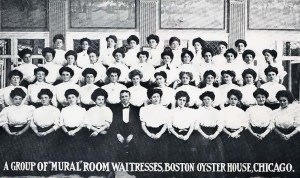

1903 In Denver, where a large part of the population eats out, a cooks’ and waiters’ strike closes large eating places. Strikes break out in Omaha and in Chicago, where a newly formed union rapidly gains 17,000 members. Restaurant owners replace black servers with white women in Chicago, while in Omaha they replace white waiters and cooks with black men.

1903 In Denver, where a large part of the population eats out, a cooks’ and waiters’ strike closes large eating places. Strikes break out in Omaha and in Chicago, where a newly formed union rapidly gains 17,000 members. Restaurant owners replace black servers with white women in Chicago, while in Omaha they replace white waiters and cooks with black men.

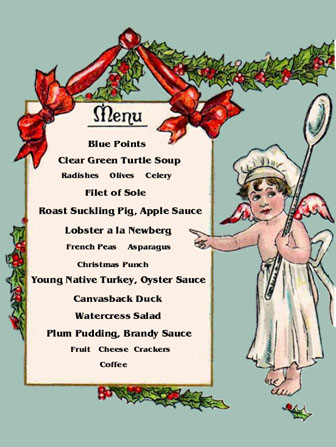

1905 Five hundred guests of insurance magnate James Hazen Hyde don 18th-century costumes and enjoy a banquet at Sherry’s. Two floors of the NYC restaurant are transformed into a royal French garden and supper is served at tables under wistaria-covered arbors set on a floor of real grass.

1906 Afternoon tea is so fashionable that NYC’s Waldorf-Astoria supplements the Waldorf Garden space by opening the Empire Room from 4 to 6 p.m. – Italian-Americans Luisa and Gerome Leone start a small table d’hote restaurant in NYC near the Metropolitan Opera.*

1906 Afternoon tea is so fashionable that NYC’s Waldorf-Astoria supplements the Waldorf Garden space by opening the Empire Room from 4 to 6 p.m. – Italian-Americans Luisa and Gerome Leone start a small table d’hote restaurant in NYC near the Metropolitan Opera.*

1908 Johnson’s Tamale Grotto is established in San Francisco with “A Complete Selection of Mexican Foods to Take Home.” – In Washington, D.C., the Union Dairy Lunch advertises that they have passed inspection with “Everything as sanitary and clean as your own home.”

1909 The Philadelphia Inquirer features a story about stylish yet practical “restaurant frocks,” showing a coral pink dress and matching hat ideal for traveling in dusty, open automobiles while visiting rural roadside inns and tea rooms.

* Later known as Mamma Leone’s.

© Jan Whitaker, 2010

Read about other decades: 1800 to 1810; 1810 to 1820; 1820 to 1830; 1860 to 1870; 1890 to 1900; 1920 to 1930; 1930 to 1940; 1940 to 1950; 1950 to 1960; 1960 to 1970; 1970 to 1980

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.