Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms.

Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms.

How they did it is a mystery not fully explained by the reputed deliciousness of their waffles nor the coziness of the Vanity Fair’s fireplace. I have not been able to find anything about their backgrounds that explains what prepared them for business success. Although contemporary publications cited them as the founders of one of NYC’s first tea rooms, it’s not clear exactly when they got their start. In 1900 Ida, 28 years old, was still living with her family in Ohio, however only ten years later she and Ada were well established in New York, running at least four tea rooms.

Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests.

Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests.

Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.”

Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.”

In 1920 they constructed a building at 3 East 38th Street, planning to relocate the Vanity Fair Tea Room because they feared – incorrectly as it turned out – that they would lose the lease for the old Vanity Fair on West 40th. Just four years later Ida took an 84-year lease on the five-story office building at the southeast corner of Madison Avenue and 33rd Street. Eventually she bought this, as well as the Fifth Avenue property which was at some point replaced by a 6-story building. By 1926, in addition to the three pieces of Manhattan real estate, Ida and Ada had also acquired a farm in Connecticut where they grew vegetables and flowers for the tea rooms.

I don’t know the eventual fate of the tea rooms, but Ida and Ada, both in their late 80s, died in Los Angeles in 1959.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

In 1890 Harry Gordon Selfridge, manager of Field’s in Chicago, took the then-unusual step of persuading a middle-class woman to help with a new project at the store. Her name was Sarah Haring (pictured) and she was the wife of a businessman and a mother. In the parlance of the day, she was needed to recruit “gentlewomen” (= middle-class WASPs) who had “experienced reverses” (= were unexpectedly poor), and knew how to cook “dainty dishes” (= middle-class food) which they were willing to prepare and deliver to the store each day.

In 1890 Harry Gordon Selfridge, manager of Field’s in Chicago, took the then-unusual step of persuading a middle-class woman to help with a new project at the store. Her name was Sarah Haring (pictured) and she was the wife of a businessman and a mother. In the parlance of the day, she was needed to recruit “gentlewomen” (= middle-class WASPs) who had “experienced reverses” (= were unexpectedly poor), and knew how to cook “dainty dishes” (= middle-class food) which they were willing to prepare and deliver to the store each day. And so — despite Marshall Field’s personal dislike of restaurants in dry goods stores — the Selfridge-Haring-gentlewomen team created the first tea room at Marshall Field’s. It began with a limited menu, 15 tables, and 8 waitresses. Sarah Haring’s recruits acquitted themselves well. One, Harriet Tilden Brainard, who initially supplied gingerbread, would go on to build a successful catering business, The Home Delicacies Association. Undoubtedly it was Harriet who introduced one of the tea room’s most popular dishes, Cleveland Creamed Chicken. Meanwhile, Sarah would continue as manager of the store’s tea rooms until 1910, when she opened a restaurant of her own, patenting a restaurant dishwasher in her spare time.

And so — despite Marshall Field’s personal dislike of restaurants in dry goods stores — the Selfridge-Haring-gentlewomen team created the first tea room at Marshall Field’s. It began with a limited menu, 15 tables, and 8 waitresses. Sarah Haring’s recruits acquitted themselves well. One, Harriet Tilden Brainard, who initially supplied gingerbread, would go on to build a successful catering business, The Home Delicacies Association. Undoubtedly it was Harriet who introduced one of the tea room’s most popular dishes, Cleveland Creamed Chicken. Meanwhile, Sarah would continue as manager of the store’s tea rooms until 1910, when she opened a restaurant of her own, patenting a restaurant dishwasher in her spare time.

A graduate of Chicago’s School of Domestic Arts and Sciences named Beatrice Hudson opened the all-male sanctum Men’s Grill (pictured) about 1914 and was responsible for developing a famed corned beef hash which stayed on the menu for 50+ years. Later she would own several restaurants in Los Angeles, coming out of retirement at age 76 to manage the Hollywood Brown Derby and again in her 80s to run The Old World Restaurant in Westwood.

A graduate of Chicago’s School of Domestic Arts and Sciences named Beatrice Hudson opened the all-male sanctum Men’s Grill (pictured) about 1914 and was responsible for developing a famed corned beef hash which stayed on the menu for 50+ years. Later she would own several restaurants in Los Angeles, coming out of retirement at age 76 to manage the Hollywood Brown Derby and again in her 80s to run The Old World Restaurant in Westwood.

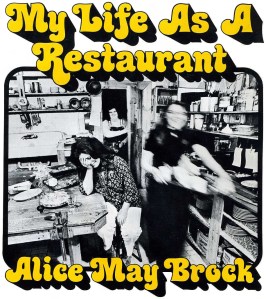

In interviews and in her two books Alice espoused the value of fresh ingredients, garlic, meals with friends, and an experimental approach to cooking. Her words convey a free-wheeling, irreverent outlook. Some examples:

In interviews and in her two books Alice espoused the value of fresh ingredients, garlic, meals with friends, and an experimental approach to cooking. Her words convey a free-wheeling, irreverent outlook. Some examples:

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.