A short time ago I had a chance to visit the fascinating second floor of the Fishs Eddy store in New York. It is piled high with not-for-sale dishware of all kinds, collected by the store’s owner Julie Gaines. The collection includes restaurant ware from the golden past when this country still produced such things. (Tours of the collection, hosted by Julie, are given periodically and booked by the New York Adventure Club.)

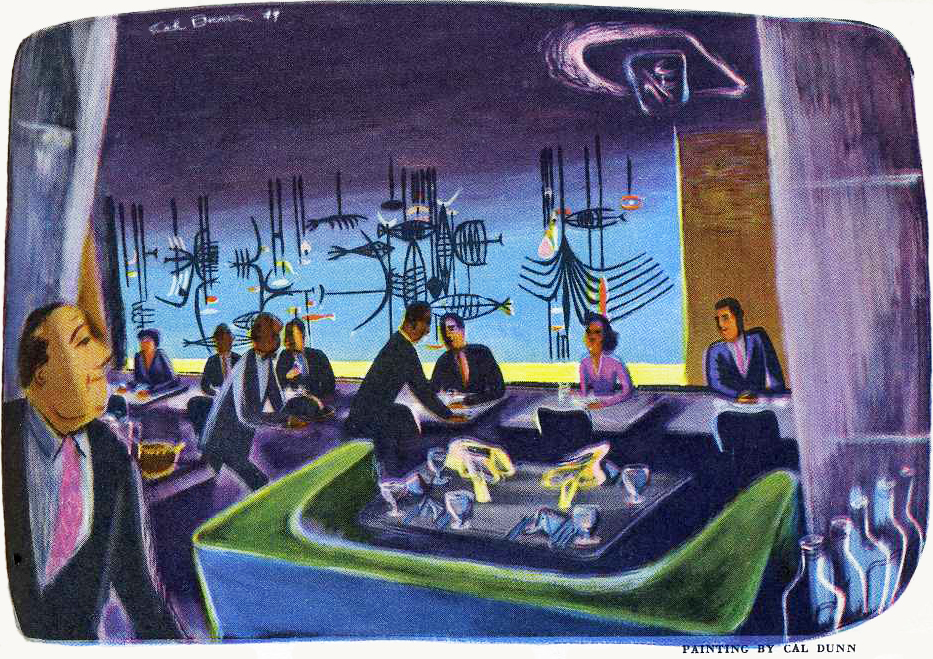

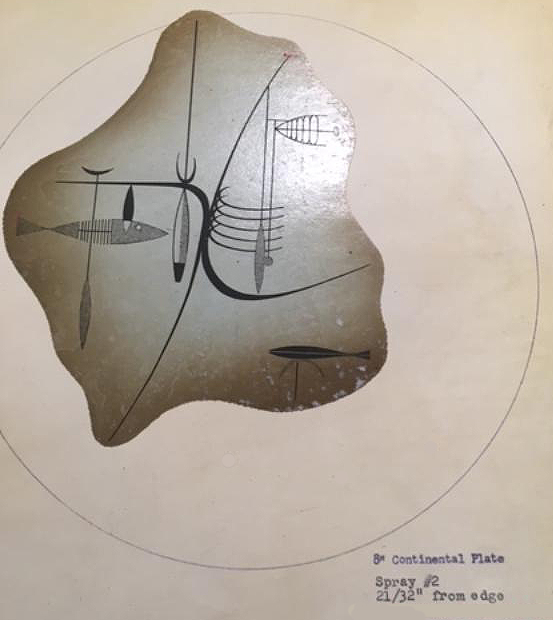

The Fishs Eddy collection also includes records from china producers that show pattern designs. A page from Shenango China in Newcastle PA — closed in the 1970s — depicted the design for a plate made for use at the Well of the Sea restaurant in the former Hotel Sherman in Chicago. (A ca. 1950 painting of the restaurant by Cal Dunn is shown at the top of this page. Below is a plate using the above Shenango design.)

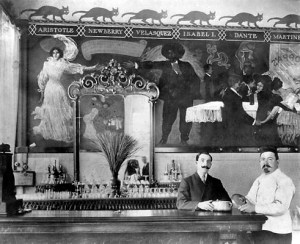

The restaurant opened late in 1948 in the hotel’s basement, which no doubt suggested an underwater theme to the hotel’s owner, the colorful and theatrical Ernie Byfield. He had also originated the over-the-top glamour restaurant, the Pump Room in the Ambassador Hotel.

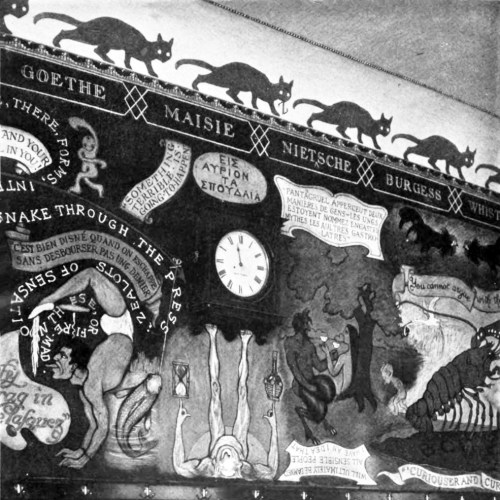

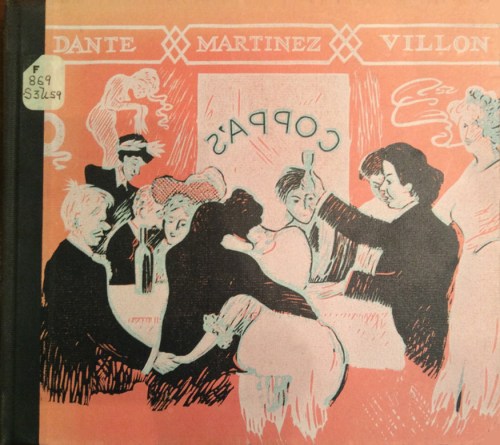

A number of abstract murals of underwater scenes by Richard Koppe, Chicago painter and student of the German Bauhaus, decorated the walls of the restaurant. One of them was used for the menu’s cover shown below. The room was further enhanced by darkness and other-worldly ultraviolet lighting.

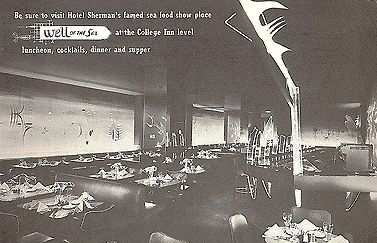

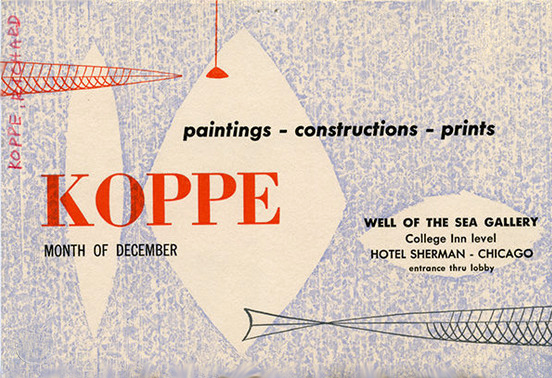

In addition to the murals, Koppe also contributed wire fish and light sculptures somewhat visible in the black and white advertisement of unknown date. The color menu depicted one of the murals.

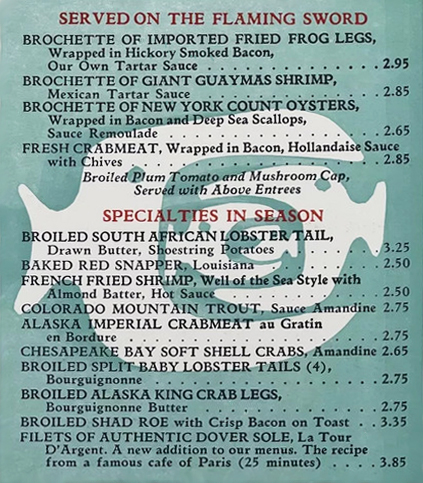

Needless to say, the restaurant specialized in fish, with frequent shipments coming in by air. It was especially known for what was called Black Clam Chowder made with Madeira wine, clams, and many herbs and spices. A portion of a menu is shown above.

Another unusual feature of the Well of the Sea was the attached art gallery in which the work of Koppe and other Chicago artists was displayed. The exhibit of Richard Koppe’s work took place in December, 1949, one year after the restaurant’s opening.

In 1968 the Sherman’s general manager explained that the ultraviolet light used in Well of the Sea was glamorous when it illuminated jewelry and white shirts but not when it lighted false teeth. But the customers liked it anyway despite the room being so dark that waiters had to assist them with flashlights in order to read menus. In 1968 a glow-in-the-dark menu was introduced to make reading easier.

Exactly when the dishware inspired by Koppe’s murals and designed by Shenango Potteries’ Paul Cook came into use in the restaurant is not known with certainty. According to Margaret Carney, whose International Museum of Dinnerware Design in Kingston NY features many pieces of dinnerware from the Well of the Sea, the design shown on the Shenango file page above was probably not used until 1954. What preceded it is unknown.

The Well of the Sea was popular from the start and stayed in business until 1972, a year before the Sherman itself closed.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.