Throughout the 20th century red and white checked tablecloths in restaurants sent clear messages to patrons: this restaurant is inexpensive, friendly, and unpretentious. Whether ethnic or “American” they suggested that the customer was in a homey place, either authentically old fashioned or old world.

Throughout the 20th century red and white checked tablecloths in restaurants sent clear messages to patrons: this restaurant is inexpensive, friendly, and unpretentious. Whether ethnic or “American” they suggested that the customer was in a homey place, either authentically old fashioned or old world.

What kind of ethnic? Beyond noting that they were never Chinese (that I’ve discovered — so far), restaurants with checked tablecloths could be Italian or French, but also German, Viennese, Spanish, British, Greek, Hungarian, or Mexican.

As for signaling old-fashioned Americanness, that could mean “Pioneer Days on the Prairie,” “Frontier Saloon,” “Old-Time Beer Hall,” “Country Barn Dance,” “California Gold Rush,” “Grandma’s Kitchen,” “Colonial New England,” or “Gay Nineties.”

I use the past tense when referring to red and white checked tablecloths, not because they aren’t still around, but because I sense their vogue has ended, at least temporarily. I would say their appeal was strongest from the 1930s through the 1970s.

The fabric itself dates far back into the 19th century. Already by 1900 checked tablecloths were seen as old fashioned. But unlike other material culture of restaurant-ing, the meanings of the tablecloths were created as much by fundraising events and celebrations sponsored by churches, clubs, and schools as they were by restaurants.

The fabric itself dates far back into the 19th century. Already by 1900 checked tablecloths were seen as old fashioned. But unlike other material culture of restaurant-ing, the meanings of the tablecloths were created as much by fundraising events and celebrations sponsored by churches, clubs, and schools as they were by restaurants.

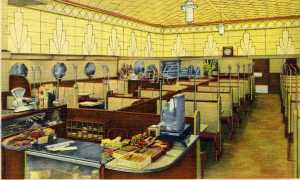

In restaurants, as well as outside them, the tablecloths have been accompanied by at least one of the following decorative touches: candles in wine bottles, lanterns, travel posters, braided garlic hung from walls, murals of villages, beamed ceilings, knotty pine paneling, sawdust floors, wagon wheels, and peasant costumes. Candles in bottles were close to mandatory.

A number of famed restaurants used the tablecloths at some point in their history. A few of them fell outside the inexpensive class such as the “21″ Club [pictured] and the London Chop House. In 1961, a New York restaurant reviewer wrote that checked tablecloths were “almost obligatory for unpretentious Gallic restaurants in this city.” Boston’s Durgin-Park used them on their long communal tables, furnishing the means for burglars to tie up the staff during a 1950s robbery. In Chicago, the Drake Hotel’s Cape Cod Room added the colorful cloths to its busy decor that included pots and pans hanging from the ceiling.

A number of famed restaurants used the tablecloths at some point in their history. A few of them fell outside the inexpensive class such as the “21″ Club [pictured] and the London Chop House. In 1961, a New York restaurant reviewer wrote that checked tablecloths were “almost obligatory for unpretentious Gallic restaurants in this city.” Boston’s Durgin-Park used them on their long communal tables, furnishing the means for burglars to tie up the staff during a 1950s robbery. In Chicago, the Drake Hotel’s Cape Cod Room added the colorful cloths to its busy decor that included pots and pans hanging from the ceiling.

Surprisingly it wasn’t until the 1980s that anyone admitted they were tired of seeing the classic tablecloths in restaurants. The ascent of Italian restaurants into the higher reaches of culinary status provided the rationale. Now, for example, reviews would begin with the assertion that Restaurant X didn’t represent, “the Italy of checkered tablecloths and melted candles in Chianti bottles, but the Italy of designer Giorgio Armani.”

It’s been quite a while since I’ve seen tables covered in red checks. Now it could be risky, suggesting not authenticity but tired mediocrity.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

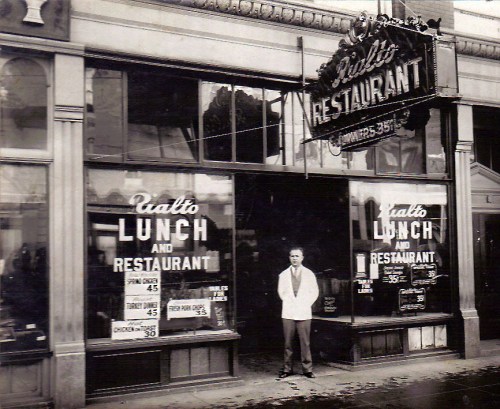

In the 1890s it was considered daring to go to an Italian restaurant and eat spaghetti. The restaurants were not in affluent neighborhoods and some middle-class people worried (largely needlessly) about how clean they were. Non-drinkers didn’t approve of the “red ink” (wine) that came with the spaghetti. Some women felt it was not ladylike to eat spaghetti in public. Then there was the garlic, which was considered seriously foreign by many Americans. But others, especially offbeat types – artists, musicians, and free spirits known as “bohemians” — loved the whole experience: spaghetti, wine, garlic, low prices, and the friendly atmosphere found in most Italian places. The future of spaghetti belonged to them.

In the 1890s it was considered daring to go to an Italian restaurant and eat spaghetti. The restaurants were not in affluent neighborhoods and some middle-class people worried (largely needlessly) about how clean they were. Non-drinkers didn’t approve of the “red ink” (wine) that came with the spaghetti. Some women felt it was not ladylike to eat spaghetti in public. Then there was the garlic, which was considered seriously foreign by many Americans. But others, especially offbeat types – artists, musicians, and free spirits known as “bohemians” — loved the whole experience: spaghetti, wine, garlic, low prices, and the friendly atmosphere found in most Italian places. The future of spaghetti belonged to them. The bohemian fad for spaghetti grew stronger in the early 20th century, particularly in lower Manhattan and San Francisco. Diners flocked to Gonfarone’s in Greenwich Village. Despite its low prices, the restaurant made money because a 50-cent dinner with a complimentary glass of wine cost but pennies to put on the table – about 2 cents for the spaghetti and a few cents for a carafe of the red California claret bought by the barrel, 40 or 50 at a time.

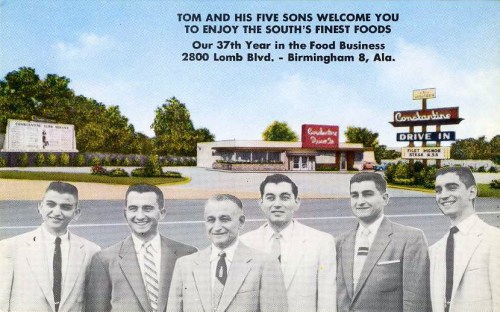

The bohemian fad for spaghetti grew stronger in the early 20th century, particularly in lower Manhattan and San Francisco. Diners flocked to Gonfarone’s in Greenwich Village. Despite its low prices, the restaurant made money because a 50-cent dinner with a complimentary glass of wine cost but pennies to put on the table – about 2 cents for the spaghetti and a few cents for a carafe of the red California claret bought by the barrel, 40 or 50 at a time. Spaghetti, Italian and non, continued as a staple restaurant dish during successive decades, in speakeasies of the 1920s, Depression dives and diners, and a variety of restaurants during the meatless months of World War II. Next came pre-cooked meatballs and prepared sauces in the 1960s and 1970s which meant even virtually kitchenless restaurants could serve spaghetti. Its cheapness and the fact that children like it also made spaghetti a favorite of family restaurants, and the basis of chains such as the Old Spaghetti Factory, the original of which was started in Portland OR by a Greek immigrant in 1969.

Spaghetti, Italian and non, continued as a staple restaurant dish during successive decades, in speakeasies of the 1920s, Depression dives and diners, and a variety of restaurants during the meatless months of World War II. Next came pre-cooked meatballs and prepared sauces in the 1960s and 1970s which meant even virtually kitchenless restaurants could serve spaghetti. Its cheapness and the fact that children like it also made spaghetti a favorite of family restaurants, and the basis of chains such as the Old Spaghetti Factory, the original of which was started in Portland OR by a Greek immigrant in 1969.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.