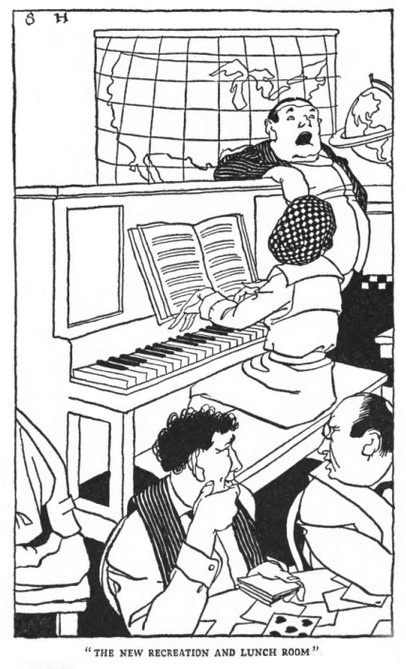

At a recent used book sale I picked up a copy of a small book of humor published in 1919 called “We Need the Business” by Joseph Austrian. I was charmed by the illustrations by Stuart Hay, several of which related to the food habits of the men in the garment trade as portrayed in the book.

The book is a series of letters written by Philip Citron, owner of a company in New York City called Citron, Gumbiner & Co. that, made women’s waists (as blouses were known then). Austrian had long worked in the clothing trade, suspenders being his specialty.

In his letters to his partner and salesmen in the field, Philip Citron mostly complains about competitors who are stealing their business. He gives the impression that most contracts the salesmen get are later cancelled when buyers find a cheaper deal elsewhere. At the same time, he is unhappy that his salesmen don’t get higher prices on the sales they make!

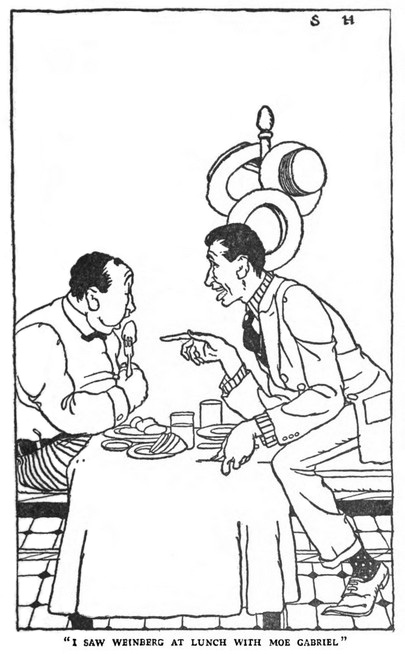

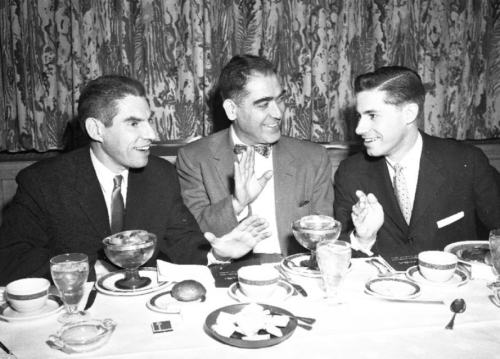

In the illustration shown at the top, Moe Gabriel, an eager salesman from a competing manufacturer, is successfully selling a bill of goods to Ike Weinberg that will result in a cancelled contract for Citron & Gumbiner. Ike actually seems far more interested in his lunch than in getting a cheap deal.

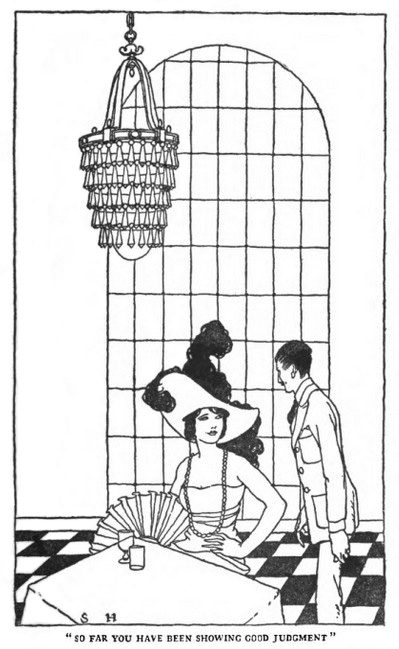

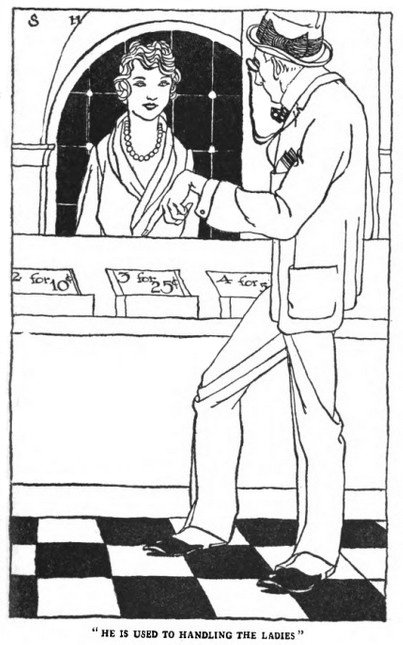

One of Citron’s salesmen is his son Abe. Philip sends him a birthday letter in which he congratulates his son on wise conduct with “the ladies.” Mingling with them, he writes, is fine if they are the “right kind of nice ladies.” The illustration suggests that Abe has other ideas. Later the reader finds out that Abe is also keeping late hours with the company’s secretary under the guise of working. Philip has no idea of what is going on.

In another letter Philip describes a trip he and his wife took to Atlantic City. He suffers from digestive problems and the little vacation is meant to get him to relax. They go to a restaurant popular with the garment trade that he refers to as the “Flyswatte” where the cooking was “high grade.” His wife asks the chef for the recipe for “a new style of cold fish” that he enjoyed there. Later, when they get back home, she prepares the dish. It makes him ill.

Philip goes to Boston to meet with a buyer from Holyoke MA named Cyprian Stoneman, from Neill, Pray & Co. He describes Stoneman [shown above] looking more like “the designer of a book like ‘The Antique Furniture of New England’” who eats pie for breakfast than an “up-to-date model shirt waist buyer.” But he is determined to find a customer in Holyoke so he settles on Stoneman, meeting him for lunch at the Café Georgette which is popular with garment salesmen and buyers – and where portions are big. Stoneman is so thin that Philip can’t imagine “where he stored all the linzen [lentil] soup, brust deckel [fatty brisket], kohlrabi, deep dish blackberry pie a la mode, watermelon and ice tea he put away.” He proves to be “one of those lemon buyers de luxe,” buying very little and wanting numerous alterations.

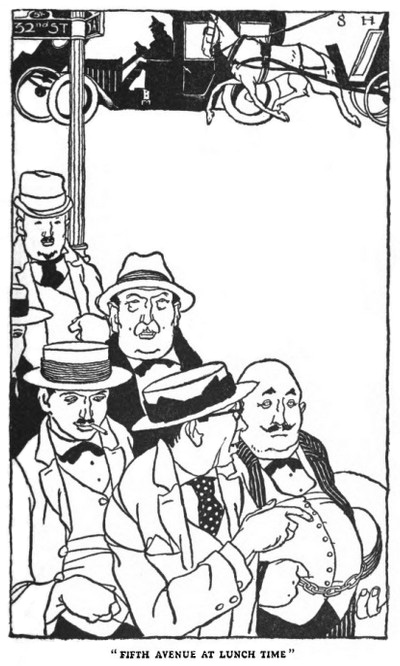

Citron, Gumbiner & Co. designer, Miss Kopyem, goes to Haines Falls in the Catskills on vacation, where she finds “the streets and porches . . . full of operators, contractors and salesmen of the ready-to-wear trade.” She does not enjoy the crowds and noise. Philip likens the scene there to “Fifth Avenue at lunch time” where, in fact, he is part of the crowds. He is shown bottom right in the drawing above.

At his partner’s recommendation Philip opens a lunch room for employees and adds a suggestion box. He removes it after it instantly becomes stuffed with 25 letters asking for additional benefits such as massages, a barber shop, soda fountain, and movies. Employees also want American chop suey, Gorgonzola cheese, marinierte herring [herring in cream sauce], strudel, gefülte fish, caviar sandwiches, welsh rarebit, and chicken a la King.

In the book’s final letter to his partner Sol, Philip reveals that the company has had its best year ever and “will show a clean net profit of about $52,000.” His stomach, he writes, “feels fine to-day.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.