Speakeasy restaurants had an unexpected and lasting effect on patrons’ dining and drinking preferences after national Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

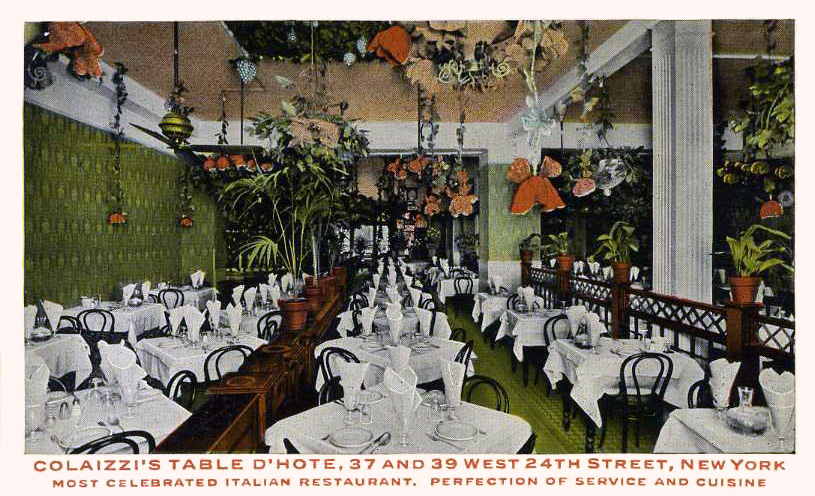

Many speakeasies didn’t serve food, but those that did were mainly located in cities and on urban outskirts. In cities, many were run by people from Italy or France, from cultures that generally did not demonize alcohol and saw wine as a normal accompaniment to dinner.

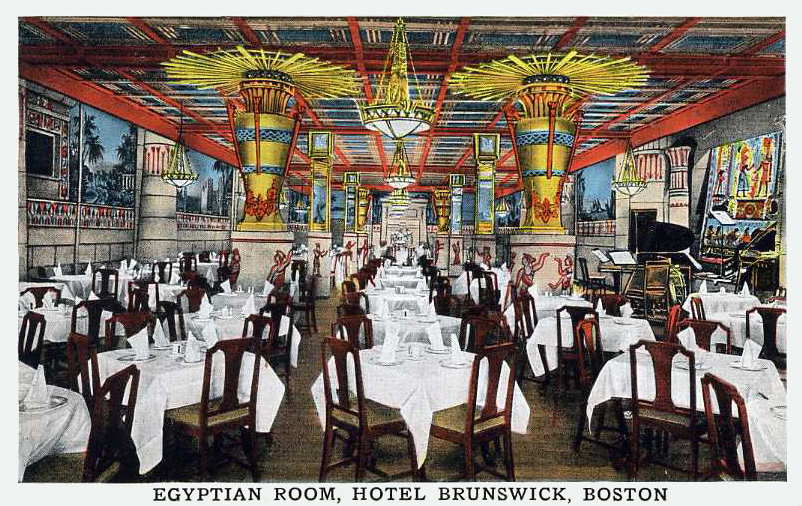

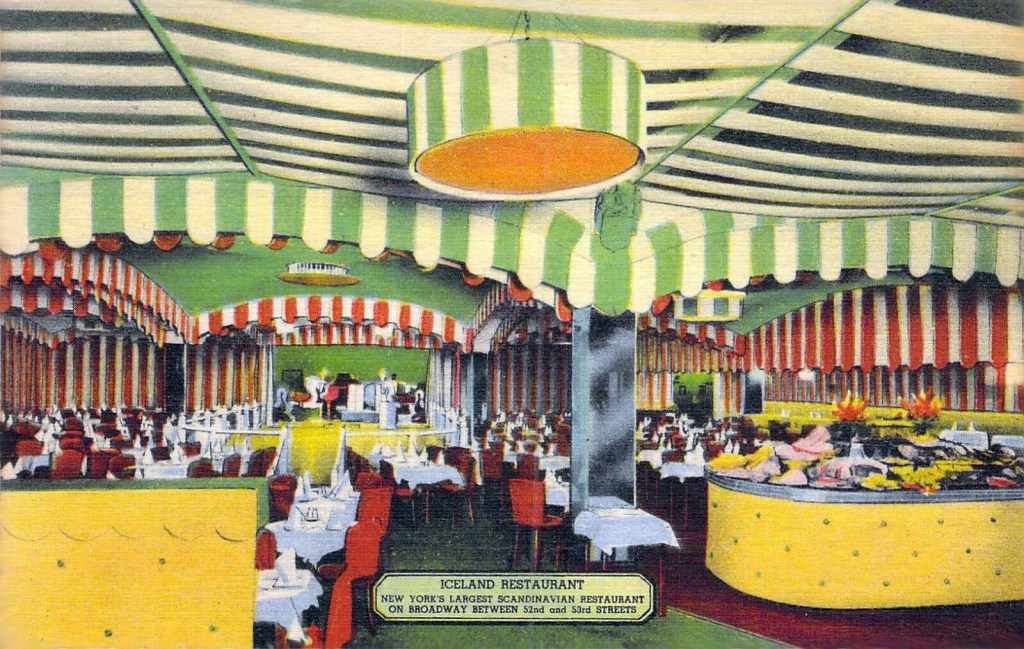

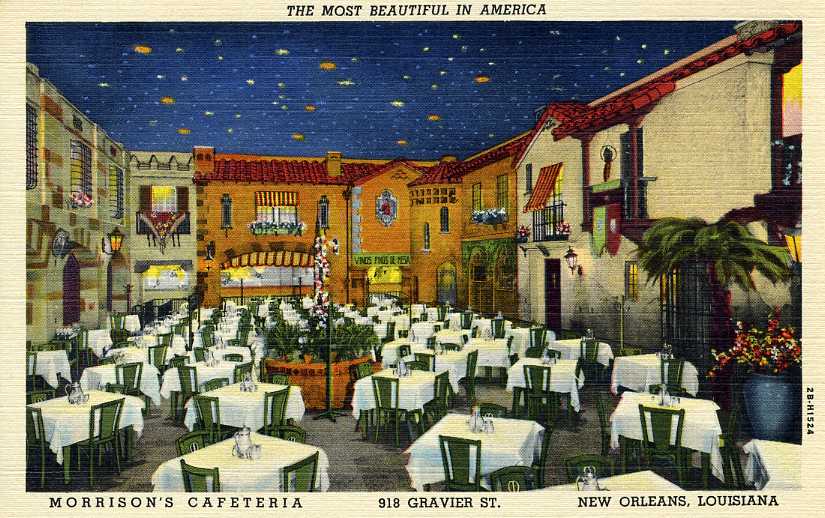

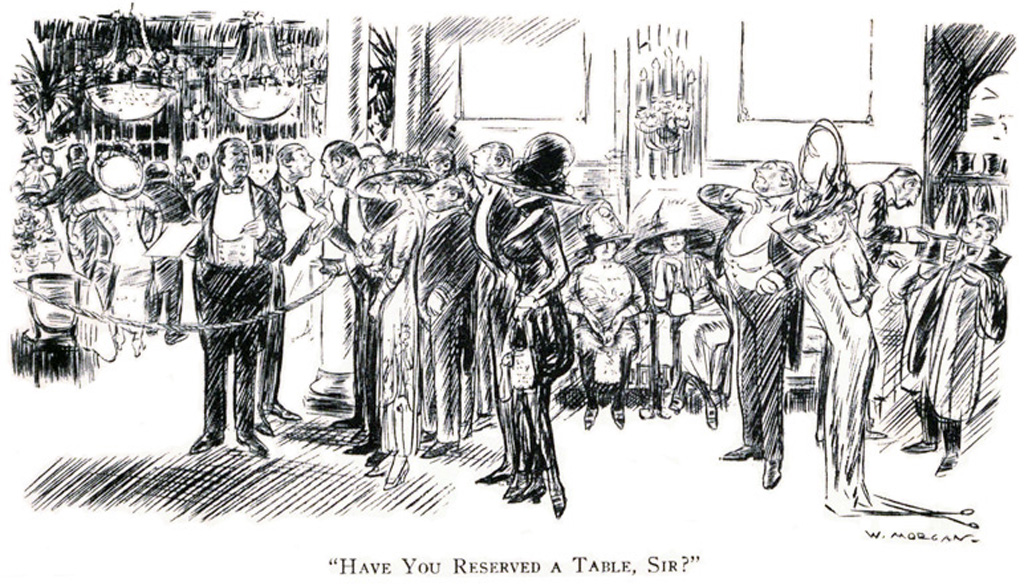

Deluxe restaurants of the earlier 20th century had closed when they lost their revenue stream from liquor, marking the end of an era of restaurant going. Their haughty formality and giant dining halls became a thing of the past. Since they had the most to lose if caught, hotels tended to observe Prohibition. But they suffered badly as guests abandoned their dining rooms for more accommodating eating places. It turned out they also liked the ambience they found in speakeasy restaurants.

Speakeasies in New York were said to have excellent food, largely because their profits allowed them to hire away the city’s best chefs from other spots. Another problem for restaurants and hotels that observed Prohibition was that they had to raise their prices to make up for the lost revenue from drinks. At the same time, speakeasy restaurants were able to lower their prices because they were making so much from drinks.

Some restaurants played it both ways. They were not speakeasies — no guards at the door, no secret password — but they were very, very careful about serving forbidden liquids only to known and trusted guests. New York’s Colony was one that tried this method, not entirely without peril. In 1925 it was padlocked by Prohibition agents for 30 days.

Another example of a respectable offender was the Bergsing Café in Minneapolis, described by the authors of Minnesota Eats as a “gentle speakeasy.” Patrons could be sure their reputations would not suffer if they ate there. As the 1929 advertisement shown above proclaims, it was popular with business leaders who evidently were not bothered by the practice of serving drinks to certain customers.

By contrast, the roadhouse known as the Hollyhocks Inn, in nearby St. Paul MN, was a true speakeasy. Although it drew a society crowd, they rubbed shoulders with serious gangsters. In fact, a co-owner of the inn was convicted of plotting with a gang to kidnap brewery head William Hamm and sharing in the $100,000 ransom. At his trial he was asked if he had run a speakeasy, drawing laughter from spectators when he answered, “I don’t know what you mean by a speakeasy.”

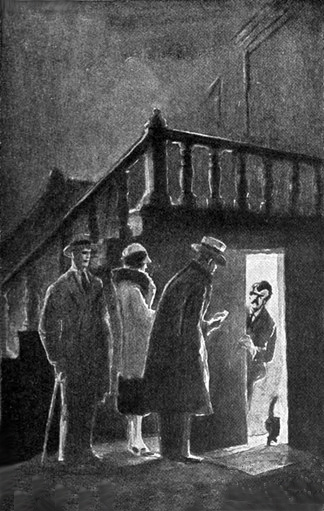

Federal agents sometimes went to great lengths to get into speakeasies. In New York three agents presented themselves as vaudeville players gossiping about fellow performers at a spot on West 46th street. They were admitted and made an arrest.

New York had so many accommodating restaurants and law-breaking customers – many of them tourists – that for many Americans in small towns the city became seen as Sodom and Gomorrah. This widened the cultural gap. As historian Lewis Erenberg put it, it created “the sense that New York was not America.”

Aside from Greenwich Village, New York’s speakeasies tended to be located on side streets, particularly in residential brownstones west of Eighth avenue in the Forties. A Brooklyn restaurant proprietor reported in the trade magazine Restaurant Management that probably half of the eating places there made “their money on other things [than] food.”

Of course, New York, where there were an estimated 25,000 speakeasies, was scarcely the only city that violated the Volstead Act. Most American cities were also said to have thousands of speakeasies in the 1920s. For instance, Chicago had the South Side and Towertown, its Greenwich Village type of area. Even Pittsburgh – where the word speakeasy first came into use in the 1880s – was well supplied. On the other hand, Los Angeles was said to be lacking in speakeasies because most Angelenos did their drinking at home.

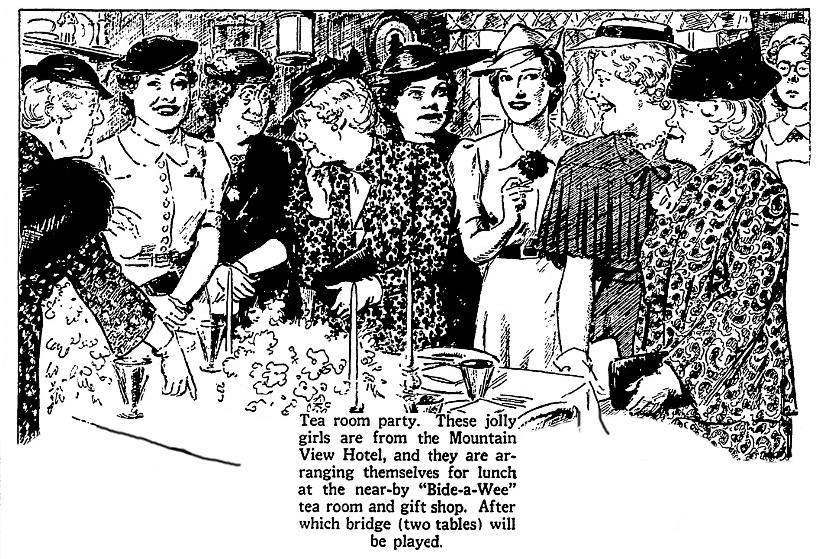

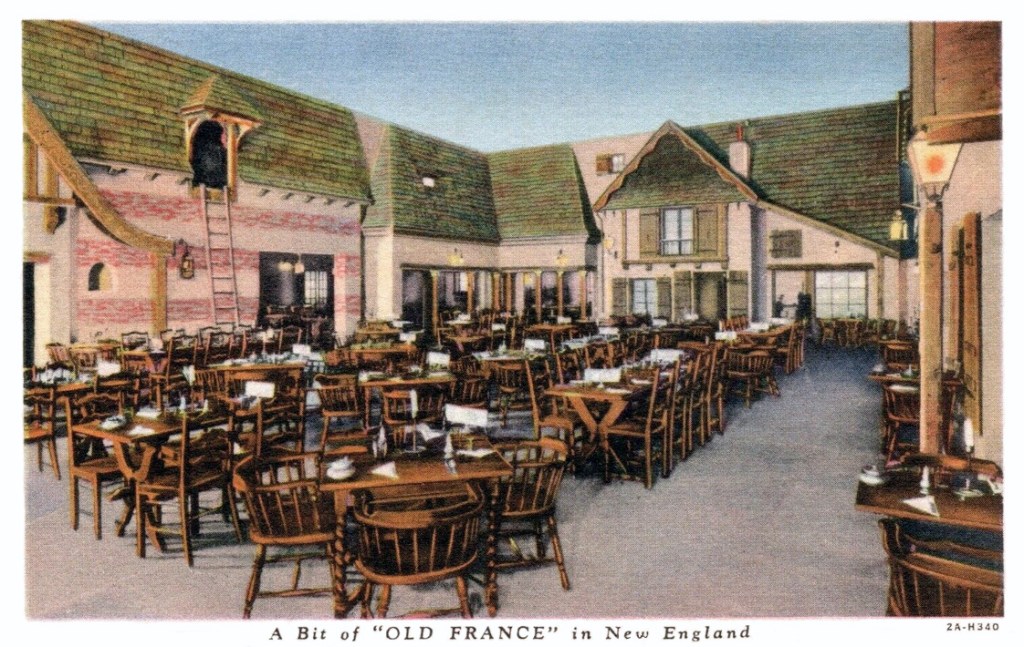

By the 1930s many speakeasy owners were plagued by gangsters who tried to muscle in for a cut. Some proprietors hoped that Prohibition would end and they could open legitimate restaurants that would be patronized by the clubby following they had developed. One of the features of the speakeasy that they hoped to capitalize on in the future was what a Life magazine story characterized as “an intimacy in the restaurant business that it never had before.” The writer Heywood Broun thought that speakeasies had been “a civilizing influence” that had helped “allay the feverish pace of American life.” They were, he thought, friendlier, with their small, quiet dining rooms, good food, accommodating waiters, and moderate charges. His concern was that the end of Prohibition would destroy that.

Others correctly felt that the public would still value small and intimate places. The Childs chain, which began to serve wine and liquor after Repeal, noticed that its booths, which had once been unpopular, were now sought after. They attributed the change to “the speakeasy influence.” Restaurant Management magazine reported in 1934 that cocktail lounges with bright ultra modern decor were being rejected by women, who preferred warmer Colonial American styles and soft lighting. Cozy Midwestern supper clubs, often located on the outskirts of town where they could avoid raids during Prohibition, showed a staying power after Repeal.

Speakeasies, it appeared, had indeed changed the public’s dining and drinking habits. Rather than lone men standing at bars, bartenders were seeing men and women at tables enjoying leisurely 5:00 o’clock cocktail hours. Diners were more knowledgeable about food and wine, and showed more enjoyment in dining out, in contrast to what one writer described as “the hurried days of eat, drink and move on to another place.”

The fondness for speakeasies also lived on long after WWII in numbers of restaurants and bars with names such as Keyhole, Hideaway, and of course Speakeasy.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.