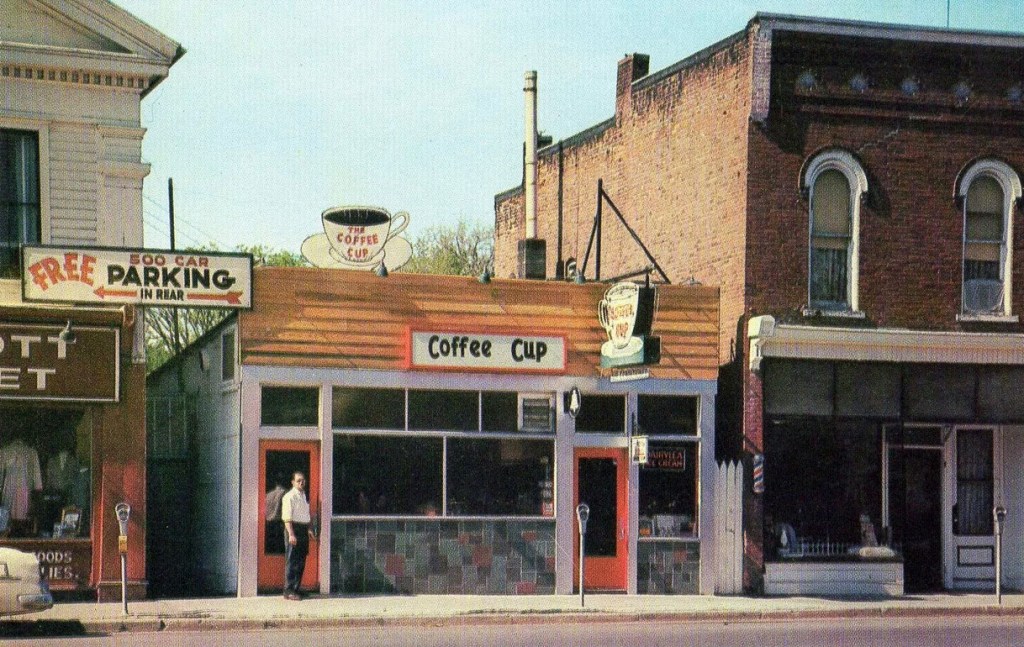

Newspaper workers, especially reporters and pressmen, made up a significant part of urban restaurant patrons in the 19th century and much of the 20th. Early on most of them were men, dropping in at all-night eateries of which there were many. Such eating places tended to choose locations close to the newspapers which were often grouped together in areas of a city referred to as “newspaper row.” [Above: advertisement for a Kansas City MO restaurant, 1940]

In his book Appetite City, about New York’s restaurant history, William Grimes notes the importance of newspapers in building nationwide interest in that city’s restaurants. He observes: “From the 1830s on, New York spawned so many papers and journals that their employees and writers constituted a sizable market, concentrated for the most part along Park Row. Moreover, journalists tended to regard oyster stands, saloons, food markets, and cafes as good copy. As the city grew and restaurants of every description proliferated, journalists turned out colorful slice-of-life stories for local and national consumption.” [Above: early 20th century postcards of newspaper rows in NY and San Francisco]

The restaurants that the newsmen patronized in the 19th century tended to be of two kinds. Either they were no frills, quick-eat places of the kinds newsboys favored, or they were places popular with artists, actors, and other free-wheeling sorts. For their evening meals, when newsmen were on their own time, they were said to enjoy the latter type of places where “there was no style, but plenty of ‘atmosphere’” such as the German “Kitty’s” on Park Place in New York with its Weiner Schnitzel and noodles.

One of New York’s best known hangouts was Bleeck’s [pronounced Blake’s] Artist and Writers, where reporters from the New York Herald were said to dominate. From its beginnings in 1925 until 1934, part of which time it was run as a so-called club in order to avoid the liquor ban, it barred women. Finally they were admitted, inspiring the unfunny comment from an old-time member, “There’ll be mayonnaise on the steak next week.” [Above: newspaper men play game to determine who will pay for drinks at Bleeck’s, 1945]

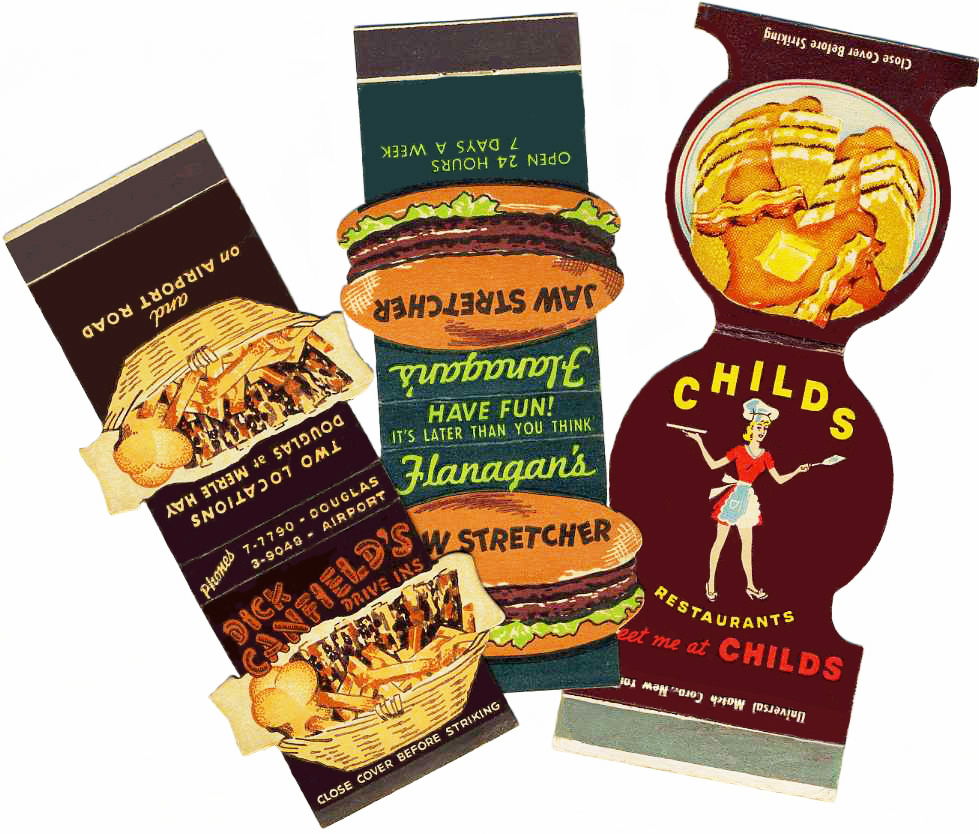

Another thriving New York restaurant with multiple locations, Crook & Duff, had a restaurant in the basement of the Times building for decades. Other magnets for newspaper folks included Jack’s, Hitchcock’s beanery, and Stewart’s in Sheridan Square. Childs’ in the Madison Square Garden building was a gathering spot for columnists, drama editors, critics, and press agents.

What might be called the Jewish newspaper row in New York was on the lower east side, which over time housed papers such as the Yiddish Daily Paper, Truth, The Day, Morning Journal, and The Forward. The Forward was located on East Broadway near the Garden Cafeteria, a gathering place for activists, intellectuals, and newspaper people, among others.

Of course New York was not the only city where newspapers, their employees, and restaurants were linked.

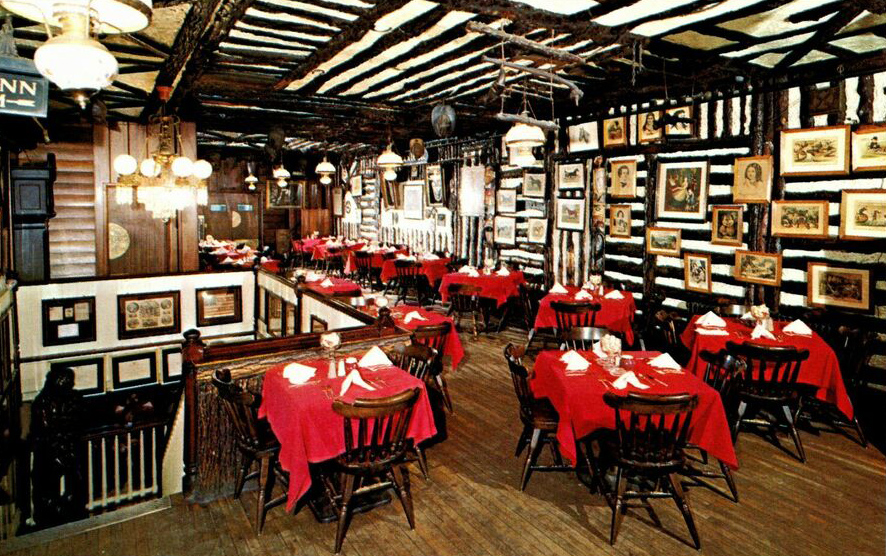

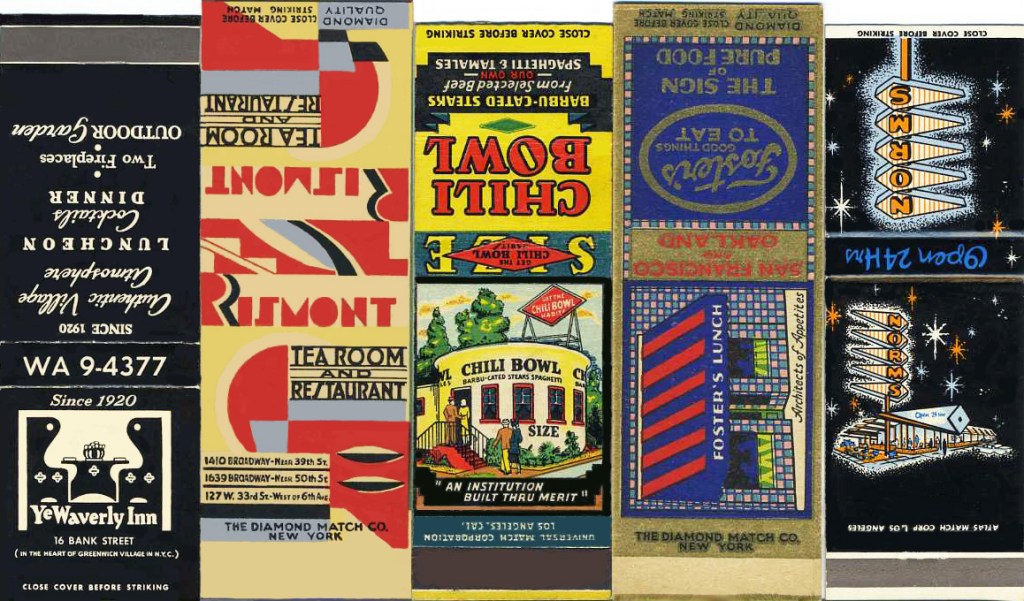

In Chicago, Schlogl’s, an old 19th-century restaurant, served as the newsmen’s club, watering hole, and dinner spot in the 20th century. Also known as Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese Tavern of America, it was located near the Chicago Daily News where its big round table hosted Carl Sandburg, Edgar Lee Masters, Ben Hecht, Thornton Wilder and other writers who worked for papers. But there were numbers of other places feeding reporters and printers, such as King’s, run by Mary King in the old Herald building. One of her daughters became a newspaper editor.

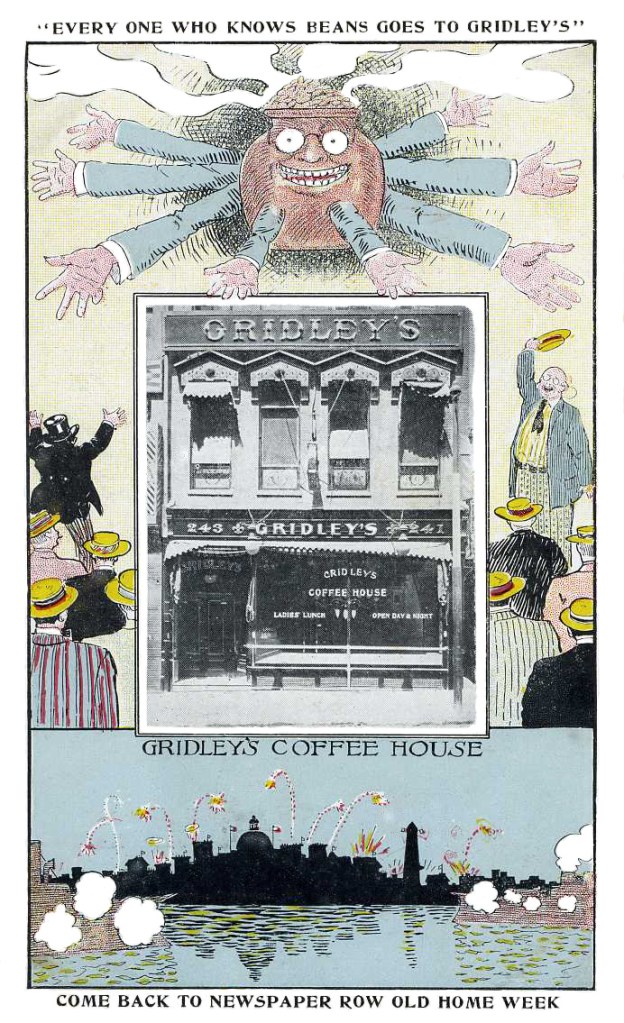

Boston had Thompson’s Spa. But as early as the 1870s, the editor of the newly founded Boston Globe established a lunch table at a nearby restaurant that endured for decades, hosting judges, lawyers, journalists, and business men. By the 1880s, Boston’s newspaper row was filled with dairy lunches and “temperance lunch rooms.” Other favorite day and night spots with the newspaper crowd were the various locations over time of Mrs. Atkinson’s, where baked beans and brown bread, corned beef hash, pies, and doughnuts were in demand for nearly 40 years. From the 1880s until 1919 Vogelsang’s was not only an eating place for newspaper men, but also for Democrats, making it a source for contacts and stories as well as for meals. [Above: Gridley’s in Boston’s newspaper row, early 20th century]

For decades in the teens and 1920s, and probably the late 19th century as well, Washington D.C. newspaper men enjoyed the French restaurant run by Count Jean Marie Perreard. He was known for his Bastille Day parties, where a tall Bastille made of boxes would be built in a corner to be attacked by guests at midnight.

St. Louis had Thony’s, where 19th century newsmen mingled with merchants and bankers while enjoying oysters brought from New Orleans on steamboats. Other newspaper men such as Eugene Field, an editorial writer in the 1870s, enjoyed the Old Beanery.

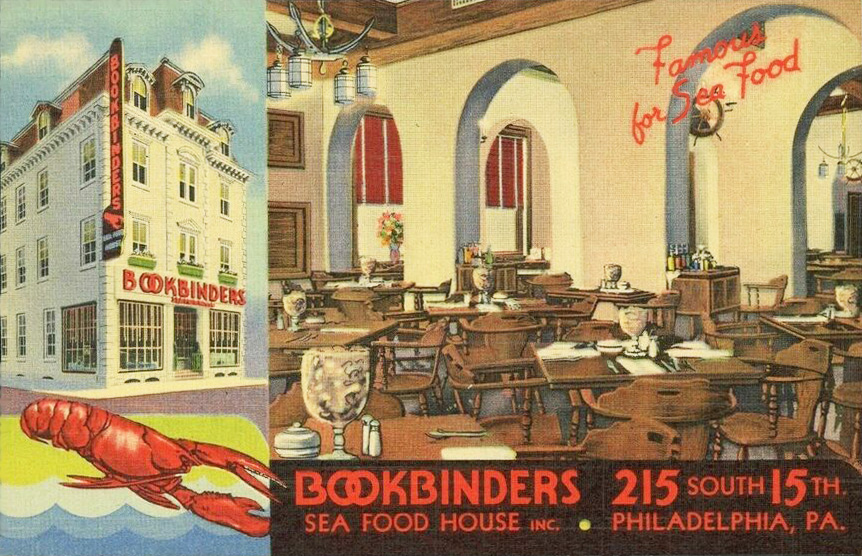

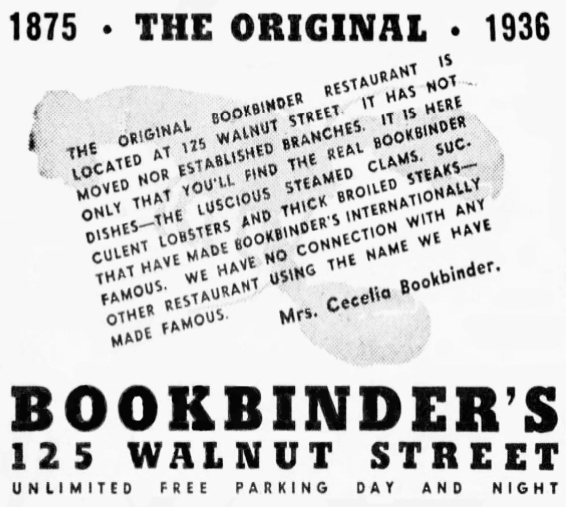

In the 1870s, Philadelphia newspaper workers almost certainly would have been found at the Model, which fed about 2,300 a day, joining a crowd that included the “sons of toil.” In the 1890s the quick lunch places grouped around the city’s big stores and newspaper offices would also have drawn them and it’s almost certain that later they would have flocked to the Horn & Hardart Automat opening in 1902. But the anti-alcohol emphasis of the city may have discouraged clubbiness.

Frequent employee patronage of eating places was only one way that newspapers influenced the restaurant world. Not only did the papers report on restaurants and carry their advertising, over time their role in promoting, evaluating, and rating them grew. Eventually there were formal reviews, and also gossip columns whose one-sentence quip about a well-known celebrity spotted in a restaurant was often enough to build the restaurant’s desirability and familiarity with readers across the U.S.

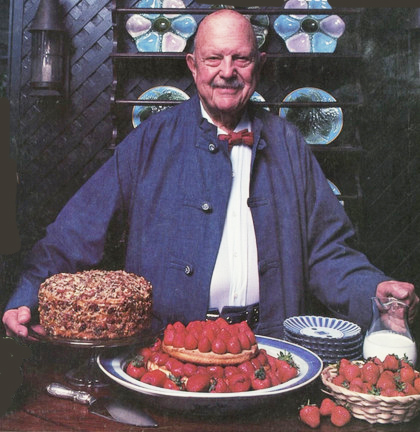

In the mid-20th century food columnists gained prominence. In 1962 Craig Claiborne began regular restaurant reviews for the New York Times. New Yorker James Beard [above] covered not just his city but the nation, running columns in many papers. When columns featured recipes, they almost always praised the restaurants that supplied them. And as has been observed by others, newspapers across the country were inclined toward favorable reviews for restaurants that were regular advertisers.

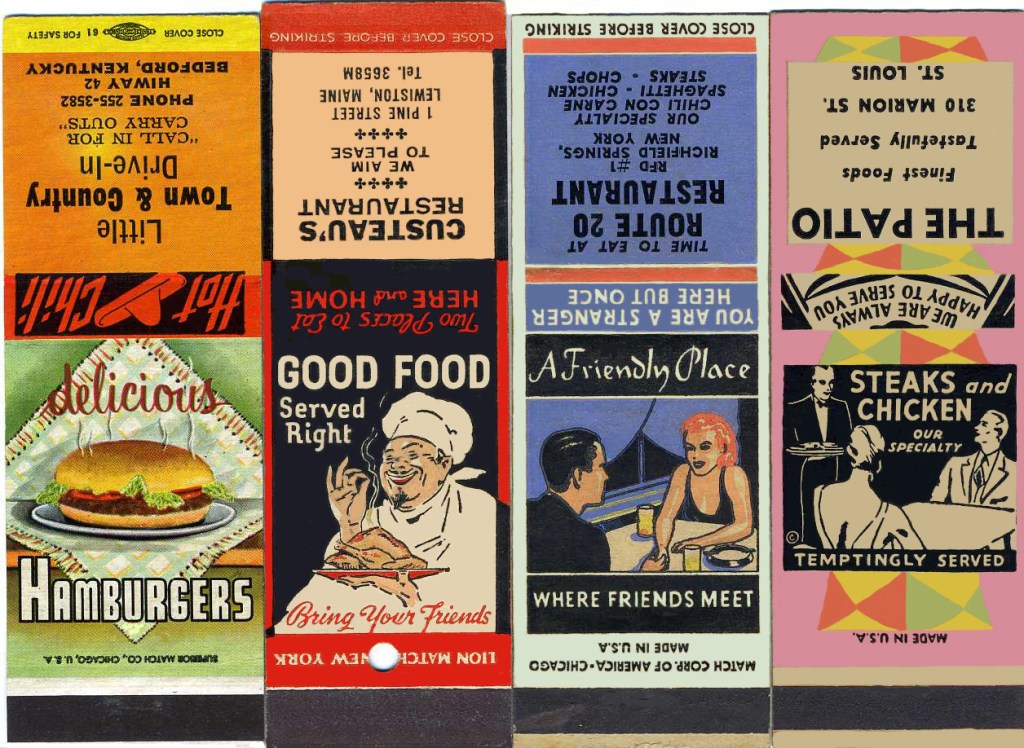

Restaurants began to turn to newspaper advertising in the 1920s, considering that the best way to attract customers. Almost certainly the most frequent advertiser nationwide in that decade was the low-priced Waldorf System with 94 units spread across 28 cities. Waldorfs were not fancy, but according to their ads they were extremely clean, with each unit undergoing inspection four times every 24 hours.

With the diminishment of newspapers, restaurant gatherings also ended by the later 20th century as did men’s clubs generally.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.