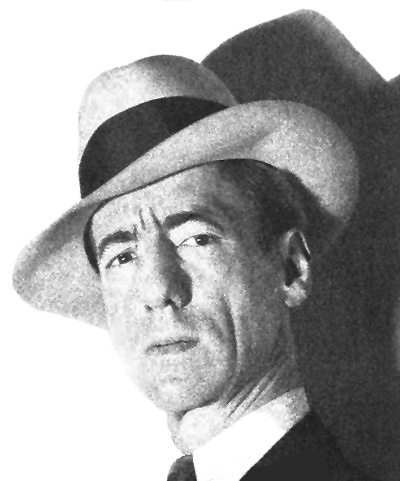

When he died in 1938 Oscar Odd McIntyre – also known as Double O McIntyre or simply Odd – was the country’s highest paid, most widely read columnist. Not only did he make New York City, particularly Broadway, familiar to newspaper readers across America, but he also informed them of the attractions of the city’s restaurants.

Considering that his success brought him a princely income, a Park Avenue address, a custom wardrobe by Lanvin, trips to Paris, and a chauffeured Rolls Royce, his writing conveyed a humble perspective. It left the impression that he was a regular small-town guy and that life in New York, when deconstructed, was less glamorous than it might seem at first, yet still captivating.

From the start of his newspaper career in Ohio he aimed at New York. As he put it, “When I was ‘the’ reporter on the daily in a small Ohio town reporting how John Hawkins spent the day in town and how Mrs. John Spivens Tuesdayed in Addison I was always dumb with admiration when I came across a guest at the Park Central Hotel who had the magic letters ‘N. Y.’ after his name.” In 1912 he landed a job as associate editor of a magazine in New York and made his big move.

His column’s target readers were, in fact, John Hawkins and Mrs. Spivens, and he relied heavily on Ohio newspapers to buy his early columns. He assumed that, like him, readers would proclaim “This is the life!” after a visit to a café in New York such as Bustanoby’s Beaux Arts. And that, like him, they would have a fascination as well with the other side of town, exemplified by the liveliness of Hester Street and the grittiness of the Bowery. He presented the city’s dark side in scenes such as one where he witnessed a patron at a nearby table in a “semi-respectable” restaurant inject morphine into his arm and then calmly resume reading his newspaper.

He revealed in a number of stories he wrote for various publications that he had a breakdown shortly after coming to New York to work for a magazine that failed three months later. He couldn’t find another job, and spent a year without leaving his sick room. He also suffered from hypochondria, claustrophobia, and agoraphobia, and depended upon his wife Maybelle to handle the business end of his writing. After seven years in which he self-syndicated, she took over and successfully negotiated a contract with a major syndicator for twice what he had been getting.

His columns were built on the notion that he spent time strolling the sidewalks of New York, but some critics suggested he actually viewed the sidewalks from the back of his limo. Another version claimed he was a recluse who rarely left his apartment and who wrote columns from memory. I’ve begun to wonder if it was Maybelle who rambled the city collecting material for him.

Whatever was the case, he entranced the nation with his observations. When they visited New York for the first time, even readers from small towns might feel they already knew the city because of what he wrote. The columnist who succeeded him recalled that when his outlander cousin came to NY, he said that because of O. O.’s columns he would need no guidance. He declared: “I’m starting at the Battery tomorrow morning, and I’ll have grilled pigs’ feet and German beer at Lüchow’s [shown above]. I’ll just glance in at Fraunces’ Tavern, but I might take a snack at the Brevoort or the Lafayette, and maybe get up to Louis & Armand’s in time for chicken Tetrazzini or a steak at Sardi’s.”

In his columns O. O. not only painted fascinating scenes of fine living in New York, but also popped bubbles about its glamor. In a similar vein he reminisced about the simple life in his old home in Gallipolis OH, but never returned there even for a short visit. He presented charming portraits of Greenwich Village, but also produced a column about its fake Bohemians and artistic pretenders. He acknowledged that there were some genuine artists living there too, adding, “they are not on display nightly in the Purple Pup, Mauve Moon and Cerise Cat restaurants.” [He did not include the Pepper Pot, shown above, but might have.]

He was also critical of New York night clubs, which he called sucker joints, as well as places with trick names such as the ones he ran into on a Los Angeles visit – the Fly Inn, Monkey Den, Hamtree, Mammy’s Shack, Quick and Dirty, and Hamburger Hank’s.

Although he frequented New York’s top restaurants, he was no gourmet. He wanted to consume the high life, but it seems mainly for its aura of princeliness rather than its culinary excellence. Although the McIntyres had a French cook, his favorite meal was said to be steak, potatoes, and chocolate cake.

His personal food preferences didn’t keep him from feeling qualified to identify the world’s best restaurants. In 1931 he named six, with The Colony at the top, then New York’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel (where he and Maybelle lived for 13 years), three in Paris: the Ritz, Foyot’s, and the Tour d’Argent, and Horcher’s in Berlin.”

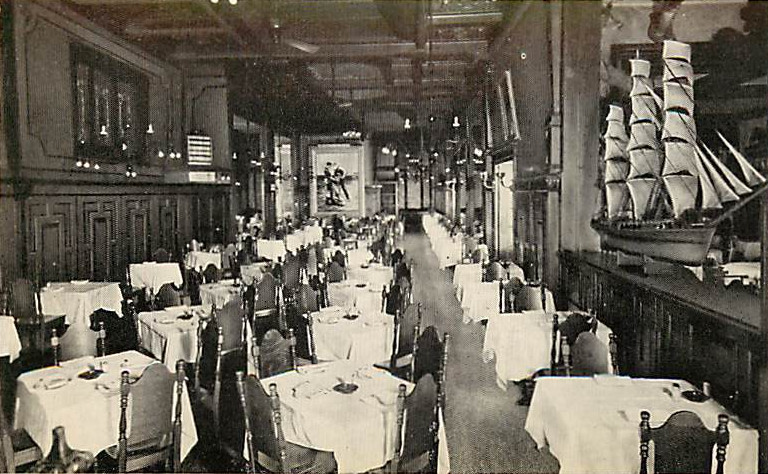

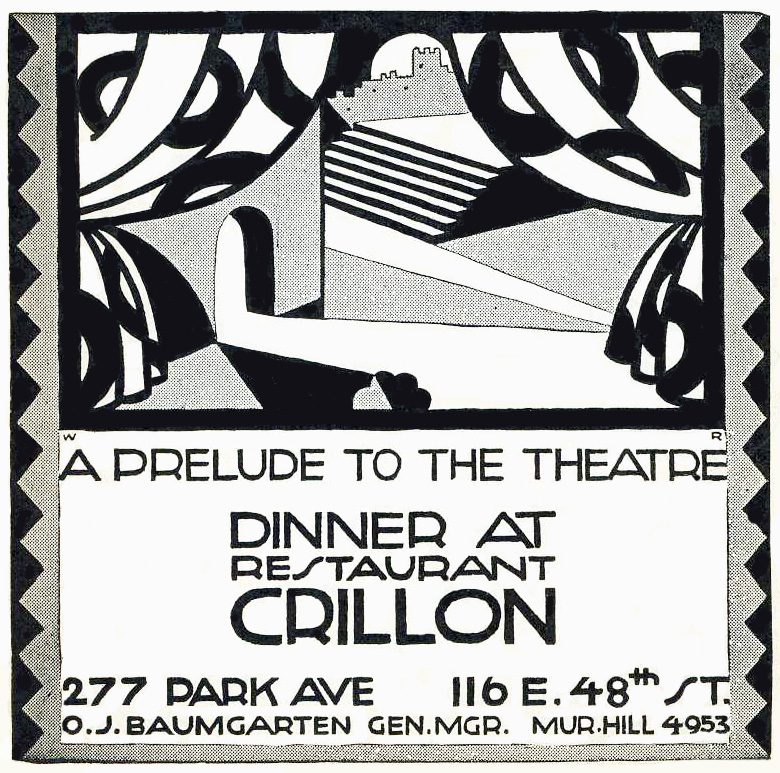

He hailed New York as “the Epicurean center of America,” but he believed it was non-New Yorkers who kept the elite restaurants in business, while the typical New Yorker followed “the eat-and-run plan of gastronomics.” So, for out-of-town visitors, he recommended the following dishes, claiming few New Yorkers even knew of them. They included caviar on a “pancake” at the Colony; noisette of venison, Grand Veneur at the Crillon; French pastry at Voisin’s; and for those preferring an unpretentious meal, doughnuts and malted milk at Liggett’s and hamburgers with chopped onions at the Owl lunch in Herald Square.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.