In 1876, one hundred years after independence, Philadelphia held America’s first world’s fair to celebrate the country’s growing importance in industry, trade, and the arts, and perhaps implicitly to recognize of the end of the Civil War.

It is notable, though, that no Southern states elected to participate. According to a historian who studied the South’s attitudes toward the Centennial, it’s likely that relatively few visitors from the South attended [“Everybody is Centennializing”: White Southerners and the 1876 Centennial, Jack Noe, 2016]. This was due both to inability to afford it and a widespread opinion reflected in Southern newspapers that the whole thing was another Yankee scam meant to benefit the North.

Another problem was that the entire country was moored in a severe six-year-long depression. Despite the drawbacks, however, the Centennial Exhibition was judged a big success, based on its efficient organization, the participation of many other countries, the range of exhibits, and the attendance over its six-month span which was reported as nearly 10 million.

When I began to think about exploring the topic of eating places at the Centennial I imagined that its restaurants and cafes would have been a novelty to many visitors who would have been delighted to experience them, with many having their first restaurant meal.

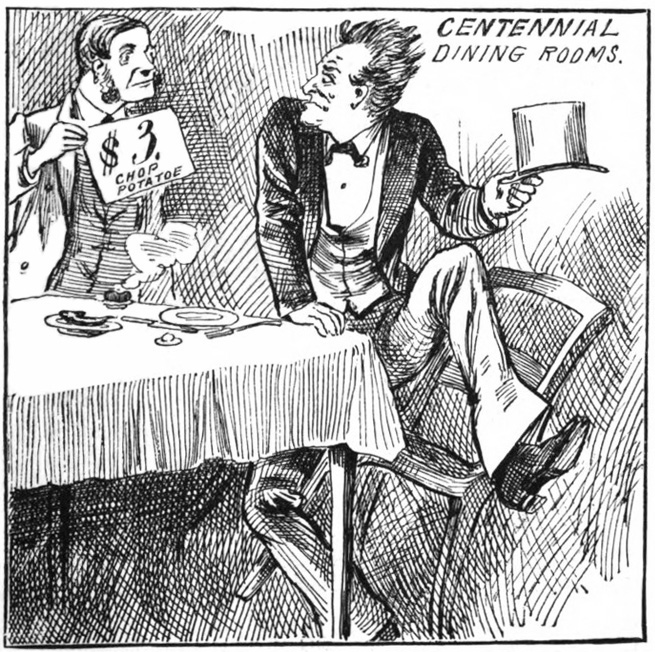

I was not prepared for the large number of criticisms, ranging from offense at snooty European waiters to complaints about menu prices and tacked on service charges. They began to pour out as soon at the Centennial began. High prices were the main target. A widely circulated Chicago Tribune story claimed that a meal could easily cost $4, with $1 charged for asparagus, and 50¢ for mashed potatoes. These were prices that rivaled fine restaurants in New York City such as Delmonico’s.

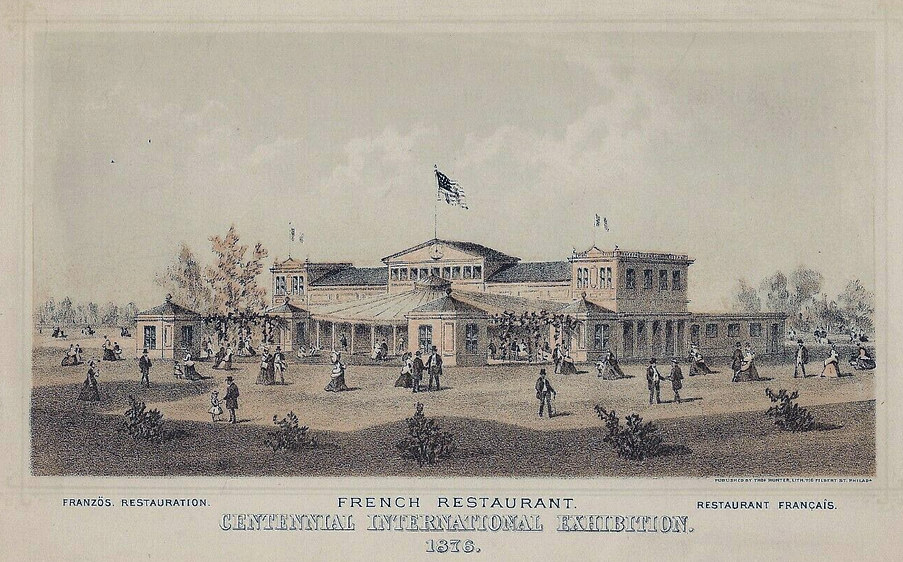

There were at least 20 restaurants and cafés on the grounds. Several seated thousands. George’s Hill Restaurant, a Kosher eating place, was capable of serving an astounding 5,000 patrons at a time. Of course most fair goers could not begin to afford these grand restaurants, each of which occupied its own massive building. Many probably found it difficult to pay even the 50¢ admission fee.

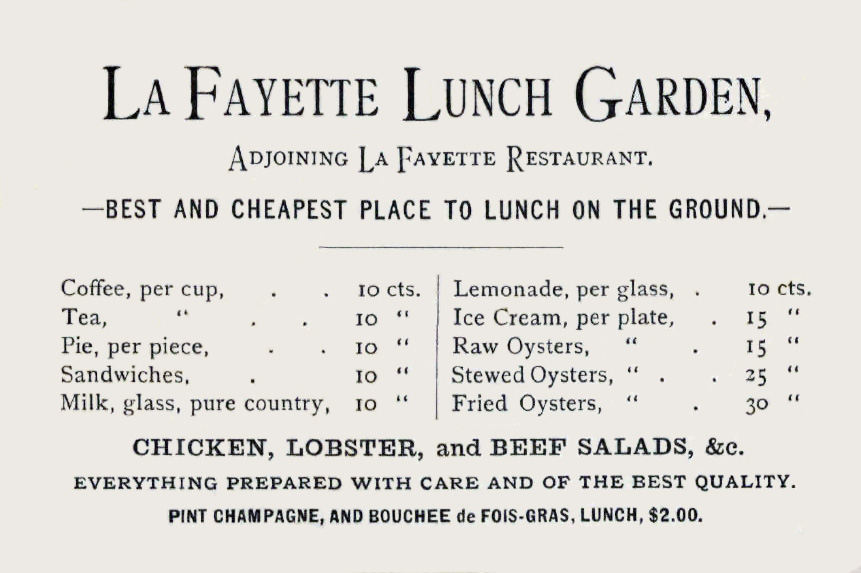

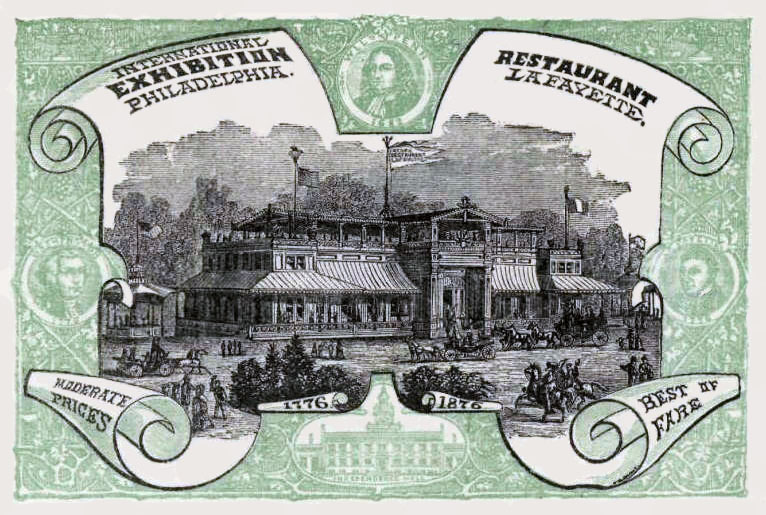

The complaints about restaurant prices leveled off a bit over time, and it may be that the Centennial Commission forced managers to lower them. Or, perhaps there was a compromise leading the big restaurants to devote part of their space to lower-priced cafes, as seems to be reflected on the menu from the La Fayette Lunch Garden shown above, part of the La Fayette Restaurant complex. There a sandwich was a mere 10¢.

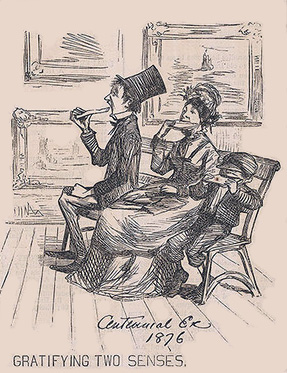

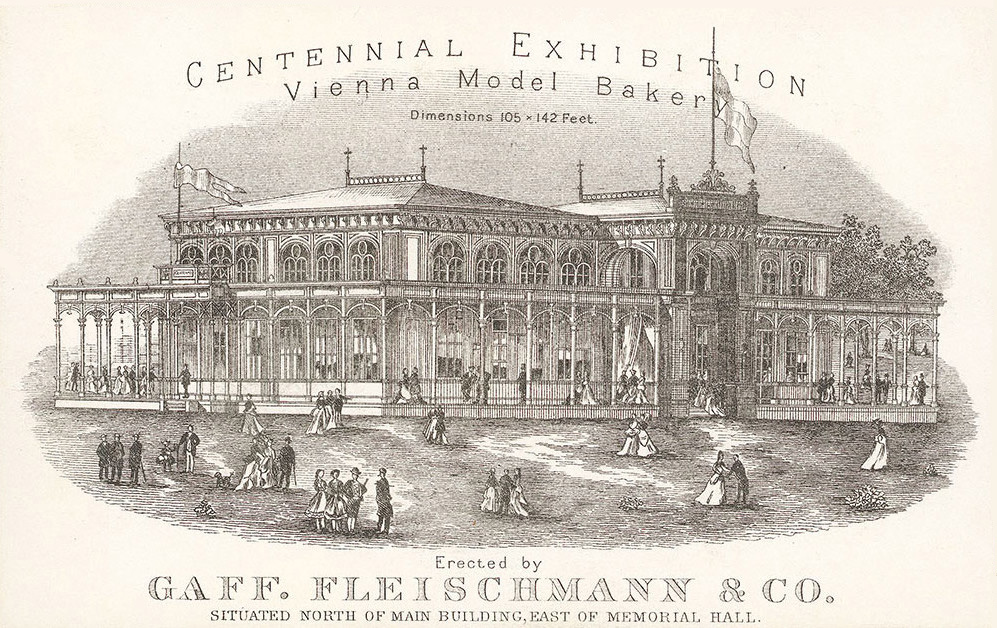

Regardless, one effect of all the publicity about high prices was that many fair goers brought their own picnic lunches [see cartoon above]. Soda and popcorn stands also proved to be very popular, as did the Vienna Model Bakery which furnished no meals but served coffee and freshly baked bread, both of a quality Americans had not experienced before. Another popular eating place was a moderately priced rustic café called The Dairy [shown below] where milk, fruit, biscuits, and pies were available.

Actually, the entire organization of the Centennial discouraged working people from attending. From the start the Commissioners decided against Sunday openings and half-price Saturdays, both of which had been operative at recent world’s fairs in Paris and Vienna. Only after disappointing attendance in the unusually hot summer months did they relent and declare a handful of Saturdays eligible for discounted fares. When the weather cooled off and attendance increased, they eliminated the discounts.

The dominance of elite restaurants at the Centennial may have been part of the same plan of discouraging, or simply ignoring, working class patrons. Perhaps the restaurant that was most resented was the “Parisian” restaurant, Aux Trois Frères Provencaux [shown here and at top]. It had a famed past dating back to the 18th century, though, unbeknownst to most Americans (if they even vaguely knew of it), it had changed hands many times, lost much of its splendor, and closed several years before the Centennial.

The Trois Frères Provencaux and the five other big restaurants at the Centennial were set up much like first-class restaurants and hotels of that time. They had large main dining rooms, a big banquet hall, a number of smaller private dining rooms, and a café. It’s likely that some of the buildings also included living quarters for the staff.

Most of the big six restaurants came in for some degree of criticism, with only George’s Hill and Lauber’s being largely exempt. George’s Hill Restaurant, on a breezy hill with a beautiful view, may have offered relief from the heat, and perhaps its customers appreciated having a kosher restaurant on the grounds. Lauber’s was already a popular Philadelphia German restaurant and it promised that its prices at the fairgrounds were identical to downtown’s.

Faring less well in public opinion were The Grand American Restaurant (disliked for its employment of foreign waiters) and The La Fayette [shown here]. The latter was perceived as a French import despite the fact that the proprietor had a restaurant in New York City. Its building was considered unattractive and its waiters were alleged to cheat customers. As was also said of the Trois Frères Provencaux, a critic claimed that its French management was unable to “comprehend America.”

The other large eating place, the Restaurant of the South [shown here], seemed to be predicated on a fascination that Northerners would have with Southern culture (including an “Old Plantation Darkey Band”), along with the belief that Southern visitors to the Centennial would want to group together in their own place. But if it was the case that few Southerners visited the fair [Noe, cited above], this would probably have taken a quite a toll on the Restaurant of the South.

In addition to meals, most restaurants and cafés also served beer and wine, despite the attempt by temperance organizations to prevent this. A California winemaker brought his wine to the Centennial to introduce it to Easterners. For $1 he also offered a “copious luncheon” with a half pint of his “California Golden Wine,” which was considered quite a bargain by the standards of the fair. Although it seems that all the cafés and restaurants had beer and wine, it’s probable that beer sales far outstripped wine sales, judging from the final report of the Centennial Commission which reported no royalties on wine.

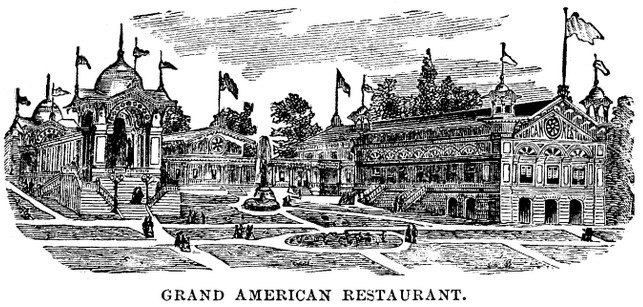

Which was the most American restaurant? Not the Grand American, which Scribner’s magazine declared had “nothing especially American about it,” but the American Lunch Counter. Associated with railroads – where lunch counters were the norm in stations – it was ridiculed by elite critics such as one in The Nation who pointed out “the excessive liberality of the bill-of-fare as compared with the actual resources of the kitchen, the negro or nondescript waiters, the unlimited pickles,” etc. The Nation’s account included the other two restaurants advertised as American — The Grand American Restaurant and The Restaurant of the South — in its complaint.

I’m left with questions about the restaurants at the fair and the fair itself. How many people actually attended? Each person had to pass through a turnstile that counted them, but since many people made multiple visits, it leaves the question whether there were 10M visitors, or 10M visits. Given that the Commissioners’ detailed final report did not show any royalties from restaurants or cafés, I can’t help but wonder if the restaurants lost money.

But surely, since many thousands ate at the fair’s restaurants, there must have been some who had good experiences.

© Jan Whitaker, 2021

For more images of the Centennial buildings and exhibits, visit the collection at the Free Library of Philadelphia.

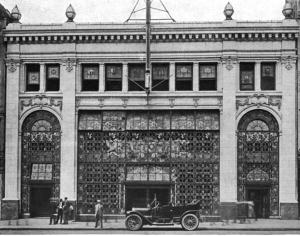

In the late 19th century owners of large popular-price restaurants began to look for ways to cut costs and eliminate waiters. The times were hospitable to mechanical solutions and in 1902 automatic restaurants opened in Philadelphia (pictured below) and New York. In both cities, a clever coin-operated set-up – and a name – were imported from

In the late 19th century owners of large popular-price restaurants began to look for ways to cut costs and eliminate waiters. The times were hospitable to mechanical solutions and in 1902 automatic restaurants opened in Philadelphia (pictured below) and New York. In both cities, a clever coin-operated set-up – and a name – were imported from  The Automat in NYC was owned by James Harcombe, who in the 1890s had acquired Sutherland’s, one of the city’s old landmark restaurants located on Liberty Street. The Harcombe Restaurant Company’s Automat was at 830 Broadway, near Union Square. Reportedly costing more than $75,000 to install, it was a marvel of invention decorated with inlaid mirror, richly colored woods, and German proverbs. It served forth sandwiches and soups, dishes such as fish chowder and

The Automat in NYC was owned by James Harcombe, who in the 1890s had acquired Sutherland’s, one of the city’s old landmark restaurants located on Liberty Street. The Harcombe Restaurant Company’s Automat was at 830 Broadway, near Union Square. Reportedly costing more than $75,000 to install, it was a marvel of invention decorated with inlaid mirror, richly colored woods, and German proverbs. It served forth sandwiches and soups, dishes such as fish chowder and  Undeterred by the first Automat’s fate, Horn & Hardart moved into New York in 1912, opening an Automat of their own manufacture at Broadway and 46th Street (pictured). It turned out that New Yorkers did indeed use slugs, especially in 1935 when 219,000 were inserted into H&H slots. But despite this, the automatic restaurant prospered, expanded, and became a New York institution. By 1918 there were nearly 50 Automats in the two major cities, and eventually a few in Boston. Horn & Hardart tried Automats in Chicago in the 1920s but they were a failure. On an inspection tour in Chicago, Joseph Horn noted problems such as weak coffee, “figs not right,” and “lem. meringue very bad.”

Undeterred by the first Automat’s fate, Horn & Hardart moved into New York in 1912, opening an Automat of their own manufacture at Broadway and 46th Street (pictured). It turned out that New Yorkers did indeed use slugs, especially in 1935 when 219,000 were inserted into H&H slots. But despite this, the automatic restaurant prospered, expanded, and became a New York institution. By 1918 there were nearly 50 Automats in the two major cities, and eventually a few in Boston. Horn & Hardart tried Automats in Chicago in the 1920s but they were a failure. On an inspection tour in Chicago, Joseph Horn noted problems such as weak coffee, “figs not right,” and “lem. meringue very bad.” The Automats hit their peak in the mid-20th century. Slugs aside, the Depression years were better for business than the wealthier 1960s and 1970s when some units were converted to Burger Kings. In 1933 H&H hired Francis Bourdon, the French chef at the Sherry Netherland (fellow chefs called him “L’Escoffier des Automats”). In 1969 Philadelphia’s first Automat closed, being declared “a museum piece, inefficient and slow, in a computerized world.” That left two in Philadelphia and eight in NYC. The last New York Automat, at East 42nd and 3rd Ave, closed in 1991.

The Automats hit their peak in the mid-20th century. Slugs aside, the Depression years were better for business than the wealthier 1960s and 1970s when some units were converted to Burger Kings. In 1933 H&H hired Francis Bourdon, the French chef at the Sherry Netherland (fellow chefs called him “L’Escoffier des Automats”). In 1969 Philadelphia’s first Automat closed, being declared “a museum piece, inefficient and slow, in a computerized world.” That left two in Philadelphia and eight in NYC. The last New York Automat, at East 42nd and 3rd Ave, closed in 1991.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.