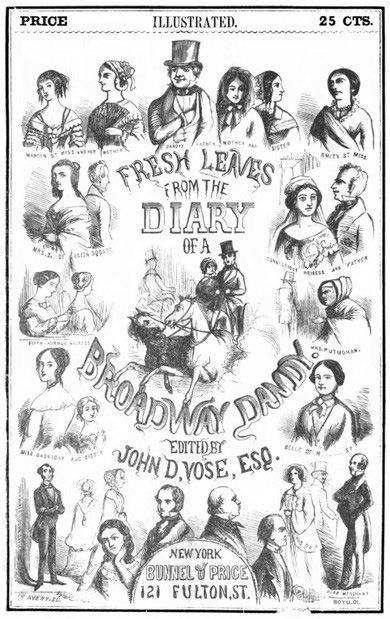

Quite by accident I discovered a book called Fresh Leaves from the Diary of a Broadway Dandy, a moral tract that conceals its true purpose by enticing the reader with details from the wild life of a roguish playboy in New York city. It was published in 1852. [Except for one Thompson’s advertisement, also from 1852, the images in this blog are from the book.]

The book was promoted with the headline “Rich and Racy.” Author John D. Vose, who had earlier been the editor of a humor publication called The New York Picayune, wrote a few other short “diaries,” one titled Seven Nights in Gotham, another called Yale College Scrapes, and a third, Ten Years on the Town. Alas, I could not find those.

The Diary of a Broadway Dandy describes the doings of one particular young man named Harry for whom money flows endlessly. At one point he enumerates some of the 30 bills he just received from fashionable eating and drinking spots around town, all of which amount to a considerable sum which he dismisses as insignificant.

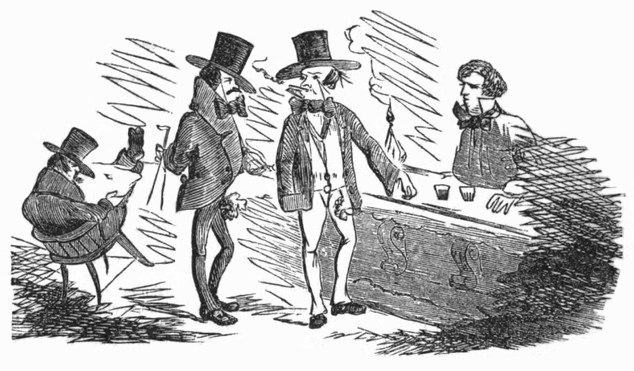

In an average week, he and his pals spend most of their time drinking uncountable bottles of booze of every kind, destroying property by breaking furniture, mirrors, and other things, and arriving back at their abodes extremely late in a drunken state. The dandies also pursue women, but just how far that goes is not detailed.

When Harry’s parents try to get him to go straight, attend church, and get a job on Wall Street, he balks and moves into a hotel. Clearly he belongs to a set of men identified in an advertisement for Charley Abel’s place on Broadway in 1852 as “the wits, fast men, and bloods of the town.”

His favorite eating and drinking places were plentiful, and included many on Broadway, among them The Arbour, Shelley’s Restaurant and Oyster Saloon, Taylor’s, and Thompson’s. (Note that at that time “saloon” meant a large roomy space, not necessarily a barroom.)

Of course, being a member of the “bon ton,” he also patronized Delmonico’s, taking his pals there for dinner one evening. He clearly liked to play the generous host not concerned about cost, but things didn’t go just as he planned this time. The day before he had ordered a dinner costing precisely $50 (about $2,000 today). When the bill came it was only for $42 and that made him quite angry. Next, he ordered a slice of white bread. Then, to make the point that he expected his exact demands to be met, he buttered the bread, placed a $50 bill on it, and ate it all.

At other places he and his friends visited, they drank vast amounts of booze and left behind a trail of destruction. On one occasion, on which nine bottles of champagne were consumed, then some brandy to settle their stomachs, he described the following:

“By some unknown way, a large mirror got cracked; but, as the landlord was a clever man, and I didn’t want to have no fuss, it being Sunday, I at once settled the loss with seven ten dollar bills, as I was not confident whether I did throw a champagne bottle against it or not. It has rather run in my mind since, that I did, but I won’t be certain. Yes, several chairs got broken, and were minus of legs and backs, yet that was laid to unknownity.”

Other casualties of drinking bouts at various times included damage to himself such as losing the heel of his patent leather shoes, staining his white pants, breaking his gold watch chain and his watch crystal, and breaking a bottle of champagne. He dismissed them, and he didn’t sound terribly contrite about an accident that happened on a Sunday either:

“Sloped from home, and took a drive with a particular friend out to the ‘Abbey.’ Found a great number out there. Our team being very dashy, attracted attention from every quarter – especially of the ladies. We drank twice, order a waiter to brush our attire three different times – made five new acquaintances, and then returned home. On our return we run the tire off of one hind wheel, causing four spokes to fall to the ground. So much for not being at church!”

By the end of the book, after the reader has enjoyed delving into the seamy exploits of the rich, the author issues stern criticisms. He concludes that it isn’t enough for a young man in New York who wants to be seen as an elite to have “the rocks,” go to the right places, or dress fashionably. Along with the rules of being a gentleman, “He must know how to be the part of a knave, a rascal,” . . . cultivating deceit “between the two gateways of virtue and vice, by sun-light and by gas-light.” Why? Because “This is a very wicked city.”

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.