Frequently when I write about the demise of a restaurant chain I can almost be certain to hear from at least one person who lets me know there is a survivor of that long-gone chain.

And, yes, that is also true of Chicken in the Rough, a franchised process for preparing fried chicken. As recently as now, Palms Krystal Bar & Restaurant in Port Huron MI offers “The World’s Most Famous Chicken Dish,” as it has for decades. In 2000 a Palms order consisted of an unjointed half fried chicken, with shoestring potatoes, hot bun, and jug of honey. Two orders cost $9.99 and they even threw in free coleslaw. In the 1930s an order usually was priced at 50 cents. [above, 1940s menu from an Arkansas restaurant]

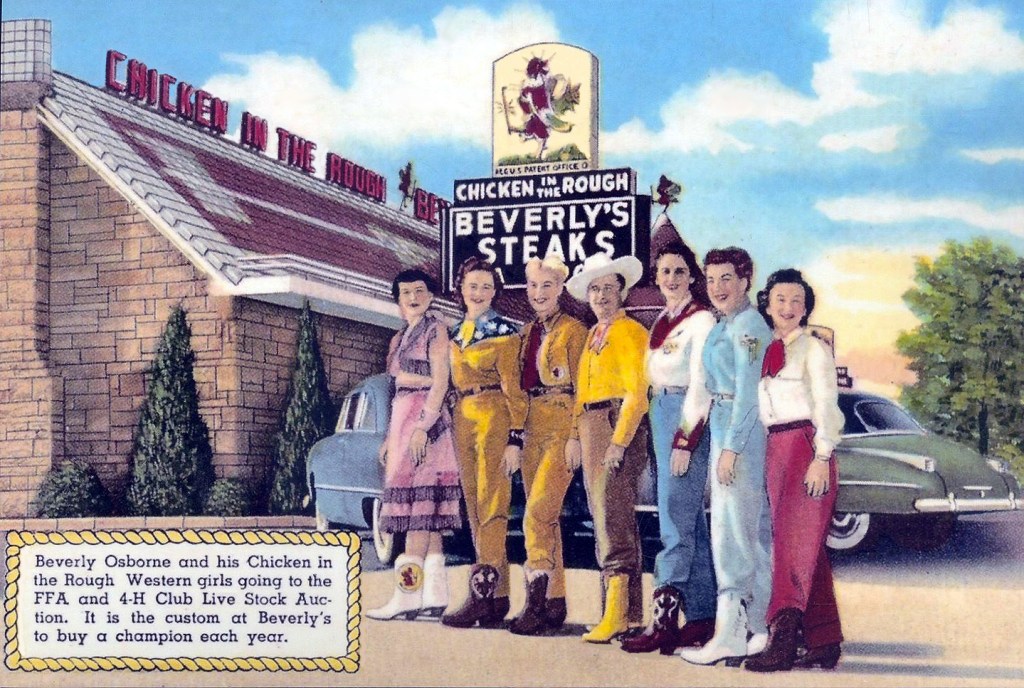

The developers of the Chicken in the Rough formula were a husband and wife team, Beverly and Ruby Osborne. They ran roughly nine cafes and waffle shops in Oklahoma City and even the 1930s Depression could not halt their enterprising spirit. [above: Beverly Osborne pictured in yellow boots]

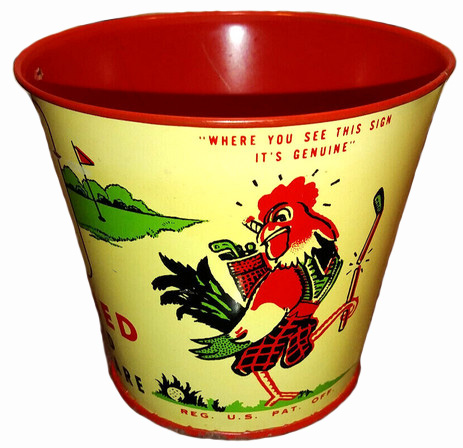

Their operations employed the magic word in modern management of that time – “system” – to streamline their operations and reduce costs. In 1936 they opened a drive-in in Oklahoma City which introduced customers to their method of preparing chicken. They soon began franchising the process and the trademark. In 1942, they patented their imprinted dishware and glasses, and the image of a chicken with a broken golf club, all of which had been in use for several years.

“In the Rough” was a perplexing phrase that often needed an explanation. It meant no silverware was provided despite the half chicken being unjointed. Evidently customers proved willing to adapt to “roughness,” although I’ve run across some evidence that over time some franchisees served the chicken in pieces. Another alternative was to serve the meal with a small metal pail filled with water for cleaning hands.

When the Osbornes opened the Ranch Room at their Oklahoma City drive-in in 1937 a large advertisement appeared in The Daily Oklahoman. Just in case anyone reading it didn’t realize the name Chicken in the Rough had been copyrighted, they were informed of this six times in the text: Yes Sir, “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) – In one year we are known from coast to coast for “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) – Served without silverware. In one year we have sold over 50,000 chickens or 100,000 orders of “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) – We are now able to offer for sale franchises on “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) . . . We took the town by storm – “Chicken in the Rough.” (Copyrighted) 50c. [Above: Madison WI franchisee]

The Osbornes were very particular about the meal’s composition, preparation, and presentation. Franchisees were required to use a freshly killed chicken, weighing 2 pounds and graded A, meaning it had been raised in an incubator and had sustained no injuries. No batter could be added to falsely make it look bigger and it had to be cooked in vegetable oil that had not been used for any other purpose. Inspectors came by regularly to make sure franchisees were following the rules.

World champion runner Jesse Owens, winner of four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics, was slated to open a restaurant featuring Chicken in the Rough in Chicago in 1953, for which he planned to use delivery wagons decorated with large images of himself racing. I could not determine the fate of that plan, but I don’t think it ever materialized.

The Osbornes sold the rights to their franchised process in 1969 and ten years later ownership changed hands once again. At the time of the first sale of the business there were only 68 franchises in 20 states left, compared to possibly 379 in 38 states at the peak, which I am guessing was in the late 1940s. Judging from a 1946 postcard that claimed to list all the U.S. restaurants with franchises then, most of the populous states without franchisees were in the Northeast. By contrast, Michigan had the most, followed by Indiana and California.

Unlike that of Harlan Sanders, who also began by selling a chicken recipe across the U.S. some years after the Osbornes, their venture remained a franchised cooking process and did not develop into a chain of restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.