In 1916 a newly arrived New Yorker named Adolph “Eddie” Brandstatter and a partner opened a café in Los Angeles. Modeling it on an unnamed New York City restaurant, they named it Victor Hugo and designed it to introduce fine French cuisine and continental service to the cafeteria-loving city.

Four years after opening the Victor Hugo, Brandstatter turned his attention to a Santa Monica project, the Sunset Inn, buying it with a new partner and selling his share in the Victor Hugo. His short tenure at the Victor Hugo was an early sign of his seeming “love it and leave it” relationship to most of the restaurants he created. Despite that, he rapidly became a well-known and well-liked public figure.

Trying to track all his restaurant ventures is a dizzying job.

By June of 1920 the Sunset Inn, which had served as a Red Cross center during WWI, had been remodeled and outfitted with a jazz band. Wednesdays were devoted to performances by Hollywood actors. But in 1922, less than two years after its opening, and despite the Inn’s apparent success, Eddie sold his share and moved on.

That same year, only a few months after departing from the Sunset Inn, he bought a new restaurant, the Maison Marcell, remodeling and reopening it. A little more than a year later he remodeled it again, renaming it the Crillon Café. Meanwhile, shortly after opening the Marcell, he had advertised the sale of his home’s furnishings, including suites from the living room, dining room, and two bedrooms, along with curtains, draperies, oriental rugs, flatware, and tableware.

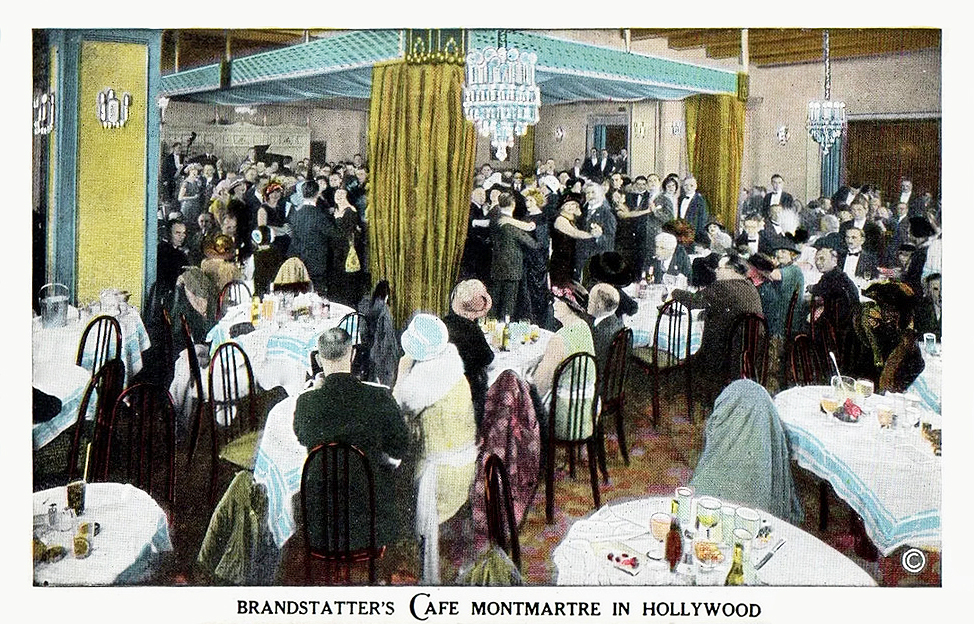

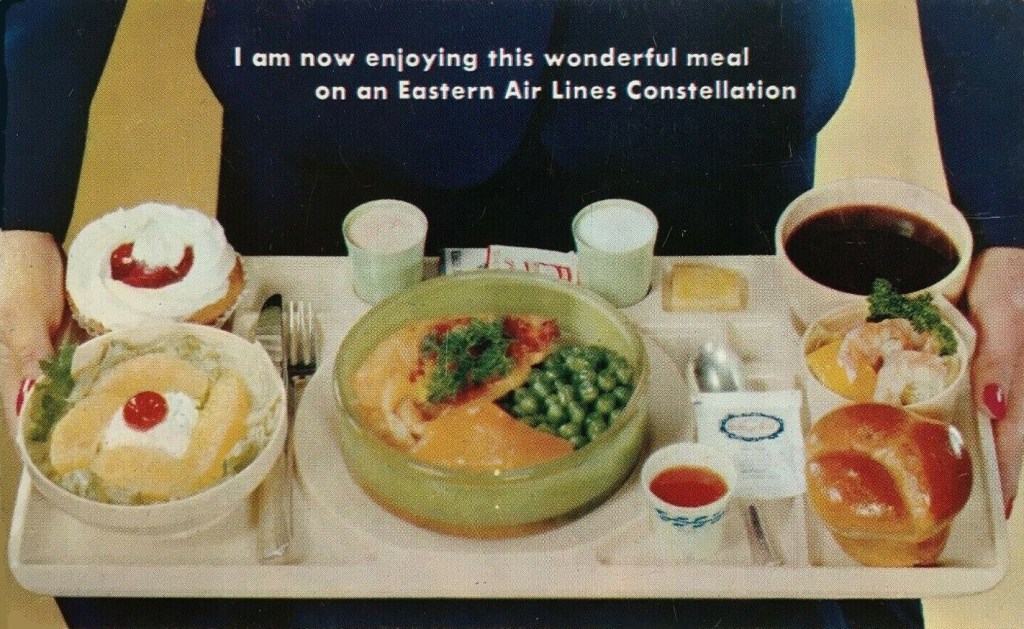

Presumably the sale was meant to raise funds for his next project, the Café Montmartre which he opened in January of 1923 on Hollywood Boulevard, with a coffee shop below it on street level. At the luxurious Café Montmartre he continued the method of luring customers that had been adopted at the Sunset Inn: linking the café to the movies, attracting stars and a gaping public. Reputedly this often involved subsidizing meals for actors short on funds. [photo: Los Angeles Public Library]

The Montmartre would become the restaurant most closely identified with him, and the longest lasting of his cafes, staying in business for nine years. He took an active role in it, greeting and mingling with guests from the film industry, as well as overall management. Yet that workload barely slowed him down. In May of 1923, the Los Angeles Examiner announced that Eddie, “Little Napoleon of the Cafes,” was planning to open “the exclusive Piccadilly Coffee House on West Seventh street between Hill and Broadway.”

1925 was a busy year of ups and downs. The Crillon closed, as did his newly opened cafeteria called Dreamland, not even open for a full year. It was the only cafeteria I’ve ever come across that had dancing!

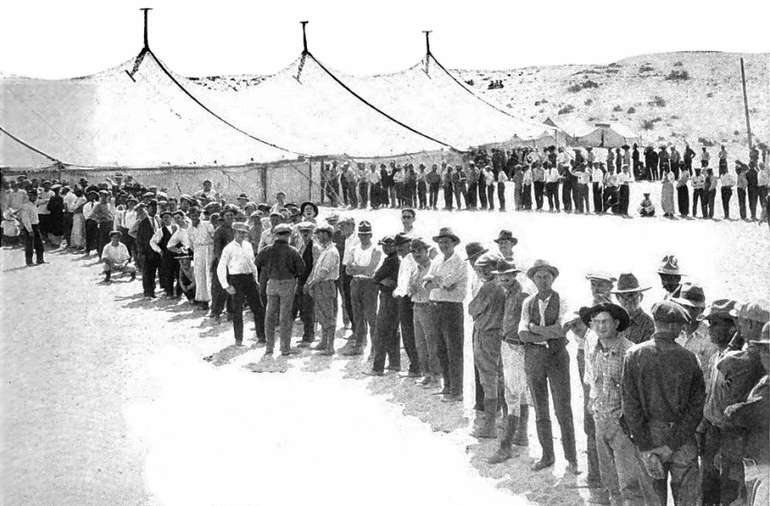

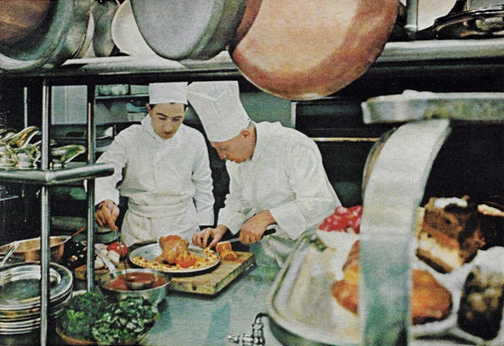

He also began a catering company that furnished food to movie casts and crews. In the next few years, the catering company took on some big projects. In one case it provided meals for 2,500 in Yuma AZ when the Famous Players-Lasky studio was filming Beau Geste. [above photo] To do that it was necessary to build a plank road atop the sand and to drill wells. The company also catered to studios when they filmed in Hollywood at night, as was the custom. That could mean serving as many as 25 studios on some nights.

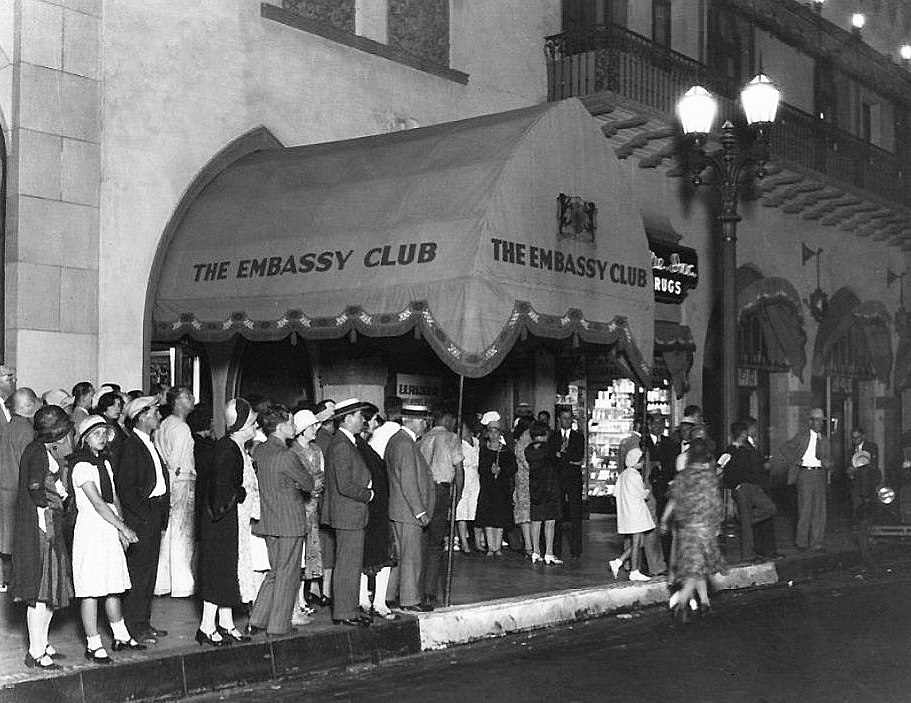

The Depression – and probably the end of silent film — took a toll. When Montmartre began to sag, he opened a swanky club next door for film people called the Embassy. It opened in 1929, closing three years later when his decision to open to the public failed to rescue it. [above: the public waits to get in] Also, in 1932 he was caught removing art objects and furnishings from the then-closed Montmartre, planning to use them in his next venture. At his trial it came out that the actual owner of the Montmartre was the realtor who had built the Montmartre and backed him by putting up capital, loaning him personal funds, and paying him a salary of $100 a week. He was found guilty and put on probation for two years.

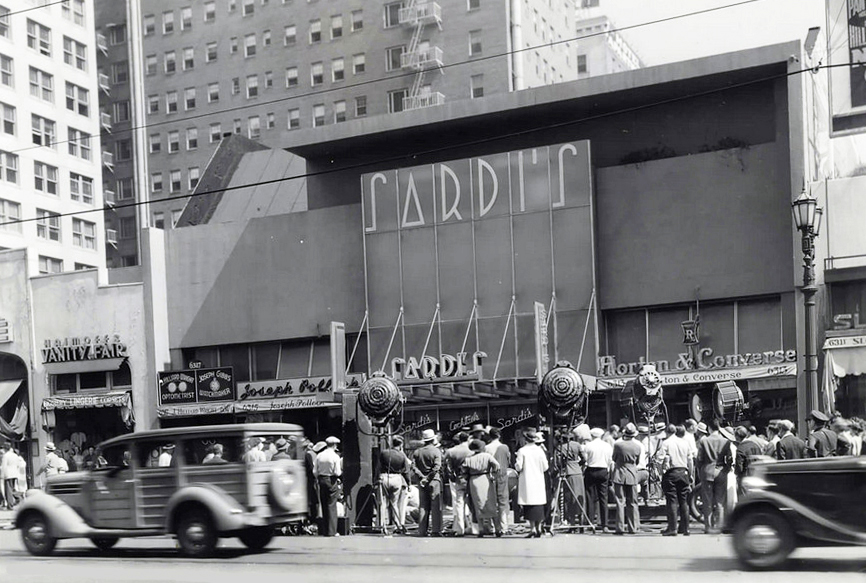

In 1933 he opened a restaurant he called Sardi’s but in no way connected to New York’s Sardi’s. With booths, tables, and fountain service, and featuring his popular set-price buffet luncheon, it quickly became a success. Its success did not stop him, however, from launching another restaurant, a chop house called Lindy’s that he seemed to have no further link to. In 1936 Sardi’s was destroyed by fire. When it was rebuilt two years later he sold his share to a partner. [rebuilt Sardi’s shown above]

In 1939 he opened his final eating place, the Bohemia Grill, with prices as low as 35c for Pot Roast and Potato Pancakes. The following year he took his own life, apparently troubled by money worries. Among the honorary pall bearers at his funeral were Charlie Chaplin, Tom Mix, Bing Crosby, and studio head Jack Warner.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.