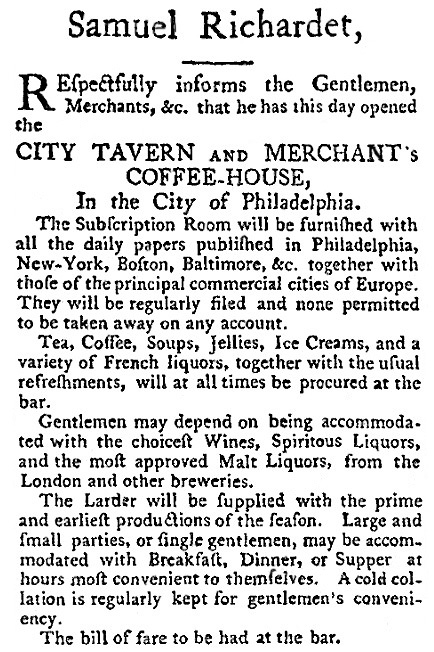

In the 1970s the National Park Service reconstructed the historic late-18th-century City Tavern in Philadelphia for use as a restaurant. An article that describes how the tavern was to be furnished noted that originally the bar was used for more than just serving alcoholic beverages. As a 1796 advertisement below shows, it also served soup which was kept hot on a stove behind the bar.

In the 1970s the National Park Service reconstructed the historic late-18th-century City Tavern in Philadelphia for use as a restaurant. An article that describes how the tavern was to be furnished noted that originally the bar was used for more than just serving alcoholic beverages. As a 1796 advertisement below shows, it also served soup which was kept hot on a stove behind the bar.

Having soup available at the bar of a tavern or coffee house sounds odd today, but it was quite common in the late 18th century and the early 19th century. Some of the places that announced soup in their advertisements were ordinaries or coffee houses that served dinners and suppers at stated times or by arrangement. But others were primarily drinking places, such as Baker’s Porter Cellar which opened in Boston in 1796. It’s main purpose was to serve “wines and spirits of all kinds” and it specialized in “genuine draught and bottled London porter.”

Having soup available at the bar of a tavern or coffee house sounds odd today, but it was quite common in the late 18th century and the early 19th century. Some of the places that announced soup in their advertisements were ordinaries or coffee houses that served dinners and suppers at stated times or by arrangement. But others were primarily drinking places, such as Baker’s Porter Cellar which opened in Boston in 1796. It’s main purpose was to serve “wines and spirits of all kinds” and it specialized in “genuine draught and bottled London porter.”

Commonly, soup became available from 11 am until 1 pm each day, though some establishments offered it as early as 8 am and others kept serving it as late as 5 pm. A few times a week prized turtle soup would appear. In those places that were more than drinking spots and served full meals, soup was usually ready by 10 or 11 am, several hours in advance of the main meal.

Commonly, soup became available from 11 am until 1 pm each day, though some establishments offered it as early as 8 am and others kept serving it as late as 5 pm. A few times a week prized turtle soup would appear. In those places that were more than drinking spots and served full meals, soup was usually ready by 10 or 11 am, several hours in advance of the main meal.

So-called restorators, which were usually run by Frenchmen, always served soup, both as a standard part of a meal and alone in the morning, possibly with a glass of wine. Like the original Paris restaurants, based on soup and taking the name “restaurant” from it, they promised that their soup would restore health for those who were feeling under the weather. Boston’s Dorival & Deguise assured patrons that “nothing will be wanting on their part, to give Satisfaction, and restore Health to the Invalids, whose Constitutions require daily some of their rich, and well seasoned Brown, and other Soupes.”

I have seen one reference to an 1820s “soup and steak establishment,” that of Frederick Rouillard who carried on after the death of Julien’s wife in Boston, as well as running a hotel in Nahant MA. His “menu” reminds me of Paris bouillon parlors that served bouillon and bouilli, the bouillon being the strained liquid in which beef and vegetables had been simmered, and the bouilli being the beef which was served with the vegetables, all of it making an inexpensive two-dish meal.

Although some 19th-century Americans disliked the “foreign” French custom of beginning a meal with soup, soup soon became a standard part of most restaurant menus, as it still is. Advertisements for morning soups became rare in the 1830s, but I don’t know whether it was because it was so well-known a practice by then that there was no need to advertise or because it was no longer done.

© Jan Whitaker, 2014

According to accounts, “D. L.” wrote his own colorful advertising copy, such as, “These hams are cut from healthy young hogs grown in the sunshine on beautifully rolling Wisconsin farms where corn, barley, milk and acorns are unstintingly fed to them, producing that silken meat so rich in wonderful flavor.” Equally over the top was his copy for Idaho baked potatoes, with references to a “bulging beauty, grown in the ashes of extinct volcanoes, scrubbed and washed, then baked in a whirlwind of tempestuous fire until the shell crackles with brittleness…” Customers who had not previously eaten baked potatoes soon learned to ask for “an Idaho.” Another heavily promoted dish, “Old Fashioned Louisiana Strawberry Shortcake,” was “topped with pure, velvety whipped cream like puffs of snow.”

According to accounts, “D. L.” wrote his own colorful advertising copy, such as, “These hams are cut from healthy young hogs grown in the sunshine on beautifully rolling Wisconsin farms where corn, barley, milk and acorns are unstintingly fed to them, producing that silken meat so rich in wonderful flavor.” Equally over the top was his copy for Idaho baked potatoes, with references to a “bulging beauty, grown in the ashes of extinct volcanoes, scrubbed and washed, then baked in a whirlwind of tempestuous fire until the shell crackles with brittleness…” Customers who had not previously eaten baked potatoes soon learned to ask for “an Idaho.” Another heavily promoted dish, “Old Fashioned Louisiana Strawberry Shortcake,” was “topped with pure, velvety whipped cream like puffs of snow.” Another factor in his success was winning catering contracts at two world’s fairs, Chicago in 1933 and New York in 1939-40. Following the NY fair he outbid Louis B. Mayer for an immensely valuable piece of Times Square real estate on the corner of 43rd and Broadway. He hired Skidmore, Owings & Merrill to design a two-story, glass-fronted moderne building (pictured), outfitted with an escalator and a show-off gleaming stainless steel kitchen. The restaurant served 8,500 meals on opening day.

Another factor in his success was winning catering contracts at two world’s fairs, Chicago in 1933 and New York in 1939-40. Following the NY fair he outbid Louis B. Mayer for an immensely valuable piece of Times Square real estate on the corner of 43rd and Broadway. He hired Skidmore, Owings & Merrill to design a two-story, glass-fronted moderne building (pictured), outfitted with an escalator and a show-off gleaming stainless steel kitchen. The restaurant served 8,500 meals on opening day. As the decade starts there are over 19,000 restaurant keepers, a number overshadowed by more than 71,000 saloon keepers, many of whom also serve food for free or at nominal cost. The institution of the “free lunch” has become so well entrenched that an industry develops to supply saloons with prepared food. As big cities grow, the number of restaurants swells, with most located in New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Massachusetts, and the Midwest where young single workers live in rooming houses that do not provide meals. Southern states and the thinly populated West, apart from California, have few restaurants.

As the decade starts there are over 19,000 restaurant keepers, a number overshadowed by more than 71,000 saloon keepers, many of whom also serve food for free or at nominal cost. The institution of the “free lunch” has become so well entrenched that an industry develops to supply saloons with prepared food. As big cities grow, the number of restaurants swells, with most located in New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Massachusetts, and the Midwest where young single workers live in rooming houses that do not provide meals. Southern states and the thinly populated West, apart from California, have few restaurants. Near the decade’s end, the “Gay 90s” commence and those who are able and so inclined pursue the good life, which increasingly includes going to restaurants for the evening. It is still considered somewhat disreputable to do this, so some people go out to dinner only when visiting another city.

Near the decade’s end, the “Gay 90s” commence and those who are able and so inclined pursue the good life, which increasingly includes going to restaurants for the evening. It is still considered somewhat disreputable to do this, so some people go out to dinner only when visiting another city. 1893 A drunken man fires five shots into

1893 A drunken man fires five shots into  1895 Competition from cafés and restaurants in Massachusetts has just about wiped out the old boarding houses where renters had all their meals supplied. One reason is that people prefer restaurants because they get to choose what and when they eat. – Boston’s Marston restaurant, established by sea captain Russell Marston in the 1840s, opens a women’s lunch room on Hanover Street.

1895 Competition from cafés and restaurants in Massachusetts has just about wiped out the old boarding houses where renters had all their meals supplied. One reason is that people prefer restaurants because they get to choose what and when they eat. – Boston’s Marston restaurant, established by sea captain Russell Marston in the 1840s, opens a women’s lunch room on Hanover Street. What a pain the rich can be. That’s the message you’ll take away if perchance you pick up The Colony Cookbook by Gene Cavallero Jr. and Ted James, published in 1972. The dedication page is plaintively inscribed by Gene, “To my father and all suffering restaurateurs.” Chapter 3 details what caused the suffering, namely the privileged customers who imposed upon him and his father in so many ways. They

What a pain the rich can be. That’s the message you’ll take away if perchance you pick up The Colony Cookbook by Gene Cavallero Jr. and Ted James, published in 1972. The dedication page is plaintively inscribed by Gene, “To my father and all suffering restaurateurs.” Chapter 3 details what caused the suffering, namely the privileged customers who imposed upon him and his father in so many ways. They

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.