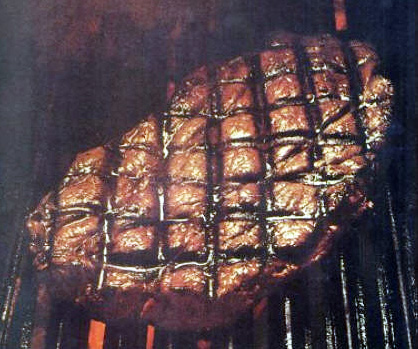

The decade began in an economic slump, putting a damper on the expensive dining trends of the 1980s. Informal dining venues met the situation by crafting new “casual cuisine” menus featuring less expensive, quickly prepared pasta dishes and grilled meat, all tailored for the Baby Boomers who formed the prime market for dining out.

Although surveys showed that Americans want healthful food choices in restaurants, beef remained extremely popular, and sales at casual steakhouses rose.

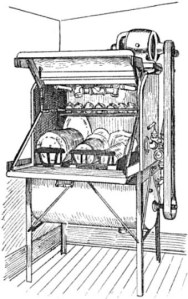

In the early 1990s restaurant chain operations emphasized efficiency and speed with microwave ovens, automatic dishwashers, and computerized systems that integrated taking orders with food preparation, as well as managing accounts and inventory. Coordination of operations enabled customers at drive-up windows to order, pay, and pick up their food rapidly.

Unable to compete with fast-food chains’ quick service and low prices, old-style casual eateries such as Horn & Hardart automats, Woolworth lunch counters, and cafeterias were disappearing. New York’s last remaining Automat, at E. 42nd St. and Third Ave., closed in 1991.

As the economy improved it became clear that luxury restaurants hadn’t vanished. The December 1990 announcement that the James Beard Foundation was forming an awards program was a sign that top chefs were not to be forgotten. Yet, despite the boost to fine dining given by the awards, fine-dining establishments continued to struggle.

New, artsy trends in plating meals emerged, among them the brief but dramatic art of stacking food into towers that wowed the eye but proved difficult to eat gracefully.

Even as elite food fads came and went, one trend appeared unstoppable: the gathering up of thousands of chain restaurants by regional owners and giant food corporations. While the media focused on top chefs and their novel dishes created in landmark restaurants, huge corporations such as Tricon Global grew even larger with many venturing into worldwide operations.

Mexican immigration doubled, reaching a new high of 8.8 million by the end of the decade and furnishing a large number of restaurant kitchen workers. Small Mexican restaurants opened to supply traditional food to the new immigrants, but by 1999 Taco Bell’s 7,000 U.S. outlets had captured 90% of the thoroughly Americanized Mexican restaurant market, serving 55M customers a week, with sales of $5.1 billion annually.

Black restaurant workers and customers had their day in court in 1993 with successful discrimination suits against Shoney’s and Denny’s. Shoney’s was found liable of charges it had set a limit to the number of Black workers it would hire in some of its restaurants, as well as hiring all-Black staffs in Black communities and all-white staffs elsewhere. Denny’s faced multiple law suits.

Highlights

1991 Six men and one woman are the first regional chefs to be honored by the newly formed James Beard Awards: Jasper White (Boston), Jean-Louis Palladin (D.C.), Emeril Lagasse (New Orleans), Rick Bayless (Chicago), Stephan Pyles (Dallas), Joachim Splichal (Los Angeles), and Caprial Pence (Seattle).

1992 A U.S. Department of Labor report on technology announces that due to increases in productivity, chain-owned restaurants “for the first time . . . exceeded the number of independently owned restaurants.”

1993 Shoney’s, at the time the third-largest chain, is fined an unprecedented $105M for racial discrimination in hiring, while Denny’s pays $54M for refusing service to Black customers, insulting them, and overcharging them.

1993 The new Food Network spotlights restaurant chefs and methods of preparation. Viewers become interested in new restaurant dishes, while rising use of garlic at home is attributed to viewers watching Emeril. Despite the interest in inventive cuisine, 1991 James Beard winner Stephan Pyles feels forced to close his Routh Street Café in Dallas.

1994 Sensing that Black patrons may have been offended by revelations regarding Denny’s discriminatory behavior, the corporate owner hires a Black Chicago advertising firm to create an image of the restaurants’ friendliness to Black customers and workers.

1995 Stacked food – aka vertical or tall food – is reportedly now passé in New York’s trendy restaurants, replaced by layering food on the plate. However, a short time later vertical food is said to be “sweeping the country.”

1996 Taco Bell is the country’s leading Mexican restaurant, with 6,867 stores.

1997 PepsiCo.’s spinoff Tricon Global, based in Louisville KY, racks up more than $7 billion in sales with its major chains Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and KFC.

1998 In a survey, Applebee’s and Cracker Barrel tie for 8th place as family favorites among the country’s 30 largest chain restaurants.

1999 The U.S. Department of Commerce declares this “The Year of the Restaurant” and the Beard award for Outstanding Restaurant goes to NYC’s Four Seasons.

© Jan Whitaker, 2023

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.