I suspect that in the 19th century more Americans ate French fried potatoes at home than in restaurants. Boiled, baked, and mashed potatoes were more common on restaurant menus than fried potatoes of any sort.

I suspect that in the 19th century more Americans ate French fried potatoes at home than in restaurants. Boiled, baked, and mashed potatoes were more common on restaurant menus than fried potatoes of any sort.

However there were probably a few restaurants that served French fries. Maria Parloa, whose New Cook Book of 1880 included a recipe for preparing French fried potatoes in a frying basket lowered into boiling fat, traveled around giving cooking lessons, and I know of at least one restaurant manager who attended them. The course of lessons she delivered in Trenton NJ in 1884 included how to make French fries, perhaps extending to the sweet potato fries that appeared in her cookbook. I have discovered at least one 19th-century restaurant menu with French fries, in Grand Forks, North Dakota, in 1894.

The reason why few restaurants served fries then was not that they weren’t popular but that they used too much cooking fat. According to Jessup Whitehead, a culinary advisor to restaurant cooks in the 1880s and 1890s, raw potatoes cooked in hot lard were the most expensive potato dish for an eating place to prepare, while baked potatoes were the most economical.

Perhaps things were starting to change in the 20th century. I’ve found a 1902 advertisement for a potato slicer for hotels and restaurants that cut “perfect French fries.” In 1911 another company produced a heavy duty model (pictured). Around this time there was a movement afoot among restaurants to charge separately for French fries rather than provide them “free” with meat or fish orders. This change could have made it possible to make a profit despite the high cost of cooking oil.

Perhaps things were starting to change in the 20th century. I’ve found a 1902 advertisement for a potato slicer for hotels and restaurants that cut “perfect French fries.” In 1911 another company produced a heavy duty model (pictured). Around this time there was a movement afoot among restaurants to charge separately for French fries rather than provide them “free” with meat or fish orders. This change could have made it possible to make a profit despite the high cost of cooking oil.

In France at this time – and probably much earlier – street vendors outfitted pushcarts with coke-fired kettles and prepared fries (“pomme frites”) on the spot for customers who ate them from paper cones. Many American soldiers in France during World War I developed the French fry habit, probably increasing demand for them in this country upon their return. In the 1920s and 1930s they began to appear on more and more menus. During World War II potatoes were scarce but after the war returning GIs, sick of mashed potatoes because of the dehydrated ones they had eaten in mess halls, hungered for French fries. Through much of the 20th century restaurant operators believed that men loved fries more than women did.

French fries were prominent on menus of postwar drive-ins. By then they were available frozen or formed from moistened dried potatoes forced through an extruder (little did the vets know they were eating dehydrated potatoes in a new guise). By 1968 the restaurant industry considered it “archaic” to make French fries from fresh raw potatoes. It was so much easier to shake frozen fries out of a bag straight into the fryer, no muss, no waste. According to Jakle & Sculle in their book Fast Food, the consumption of frozen potatoes went from 6.6 pounds a year per person in 1960 to 36.8 pounds in 1976. In this same period French fries made the short hop from drive-ins to their successors, hamburger chains such as McDonald’s.

French fries were prominent on menus of postwar drive-ins. By then they were available frozen or formed from moistened dried potatoes forced through an extruder (little did the vets know they were eating dehydrated potatoes in a new guise). By 1968 the restaurant industry considered it “archaic” to make French fries from fresh raw potatoes. It was so much easier to shake frozen fries out of a bag straight into the fryer, no muss, no waste. According to Jakle & Sculle in their book Fast Food, the consumption of frozen potatoes went from 6.6 pounds a year per person in 1960 to 36.8 pounds in 1976. In this same period French fries made the short hop from drive-ins to their successors, hamburger chains such as McDonald’s.

Perhaps because of their mid-century popularity as side dish to sandwiches, French fries were shoved aside in the white tablecloth restaurants of the 1960s and 1970s by the old-fashioned baked potato which returned to favor as the prestigious accompaniment to steak and prime rib, especially when served with sour cream and fresh, er, frozen, chives.

© Jan Whitaker, 2010

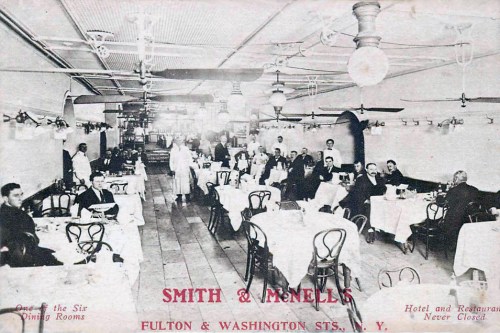

All things considered, the best restaurants that this country has produced probably have been unpretentious, inexpensive, high-volume eateries located close to sources of fresh food. In 19th-century New York City’s Smith & McNell’s, across from the booming Washington Market, was a leading example of the type. Its patronage came largely from dealers, farmers, and customers who worked and shopped at the market. Around 1891 the restaurant reportedly provided more meals than any eating place in the city, as many as 10,000 a day.

All things considered, the best restaurants that this country has produced probably have been unpretentious, inexpensive, high-volume eateries located close to sources of fresh food. In 19th-century New York City’s Smith & McNell’s, across from the booming Washington Market, was a leading example of the type. Its patronage came largely from dealers, farmers, and customers who worked and shopped at the market. Around 1891 the restaurant reportedly provided more meals than any eating place in the city, as many as 10,000 a day. There are many discrepancies in accounts of this restaurant’s history but it seems most likely it was established in the late 1840s by Thomas R. McNell and Henry Smith. McNell was an Irish immigrant, born sometime between 1825 and 1830. According to one account he and Smith had been night watchmen before taking over the coffee house run by Frederick Way on Washington Street near the market. Both McNell and Smith became wealthy and McNell acquired a lordly estate in Alpine, New Jersey, as well as a California ranch. He continued working in the business until a ripe old age and died in 1917 a few years after the restaurant (and associated hotel) closed.

There are many discrepancies in accounts of this restaurant’s history but it seems most likely it was established in the late 1840s by Thomas R. McNell and Henry Smith. McNell was an Irish immigrant, born sometime between 1825 and 1830. According to one account he and Smith had been night watchmen before taking over the coffee house run by Frederick Way on Washington Street near the market. Both McNell and Smith became wealthy and McNell acquired a lordly estate in Alpine, New Jersey, as well as a California ranch. He continued working in the business until a ripe old age and died in 1917 a few years after the restaurant (and associated hotel) closed.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.