There is nothing as interesting (to me) as a memoir about a restaurant from an insider who reveals its workings not usually known to customers. Papa’s Table d’Hôte by Maria Sermolino is such a memoir, published in 1952, decades after her father’s ownership of the New York City restaurant, Gonfarone’s.

Maria’s career as an editor and writer was extensive. After graduating from the Columbia School of Journalism and spending a couple of years writing about post-WWI conditions in France, she interviewed Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini. Later she worked for Time, was the editor of The Delineator and for 11 years an associate editor for Life magazine. She attributed her lifelong unmarried status to overhearing conversations about women among waiters and from male guests invited by her father to join him at his table. [above, Maria at age 25, in 1920, the year she interviewed Mussolini]

Gonfarone’s began in business around the turn of the last century as an Italian pension-type eating place, transitioning into a bohemian resort for Greenwich Villagers. It was run initially by Caterina Gonfarone who operated it in a basement on the corner of Eighth and McDougall streets. She soon partnered with Maria Sermolino’s father, Anacleto, who saw to it that the dining room was moved upstairs. Then, as neighboring residences were acquired by the partners, the popular Latin Quarter table d’hôte expanded to eventually accommodate 500 diners at a time. Sermolino soon acquired the restaurant from Madama Gonfarone, but kept her name.

After the Sermolino family moved into the complex of buildings (which also included a small hotel), Maria spent much of her childhood in the restaurant. Chapter 6 of her book is entitled “The Barroom Was My Playground.” She assisted her mother, the restaurant’s cashier, by spotting waiters who failed to pay her mother for drinks they ordered for customers at the bar. (They would have been reimbursed later, but without paying first they were able to keep the customers’ payments for themselves.)

But that is not the only way in which the staff tried to make extra money on the side. Dishwashers sold food scraps and fat to a company that made soap, with higher prices paid for barrels with more fat. On occasion Madama Gonfarone would catch a dishwasher pouring a large tin of unused lard into a barrel for a higher payoff. It was also common for the staff to smuggle out bottles of wine, chickens, lobsters, and other choice food items when they left at night. Her father refused to institute routine searches because he thought it would be bad for morale.

Because the restaurant was connected to a hotel, the bartender also acted as the room clerk. He took advantage of his position by renting rooms to prostitutes, even on occasion — when she was away — renting Madama’s room for more than double his usual charge.

Not all the restaurant’s customers were treated equally. Waiters would see to it that their favored regulars got larger portions, choicer cuts of meat, and less melted ice in their drinks. A standard menu, 50 cents on weeknights and 10 cents more on Saturdays and Sundays, featured Antipasto, Minestrone, Spaghetti, Salmon with Caper Sauce, a Sweetbread, Broiled Chicken or Roast Beef, Vegetables, Potatoes, Green Salad, Biscuit Tortoni or Spumoni, Fresh Fruit, Assorted Cheeses, and a Demi-tasse. In all likelihood the portions would have usually been on the small size.

“By the simple act of ordering spaghetti an American was plunged into a foreign experience,” observes Sermolino. [above, 1916 advertisement from The Greenwich Village Quill; below, 1919 Quill]

All meals came with a glass of California claret, which the restaurant bought 40 or 50 barrels at a time, reducing their cost to ten cents a gallon. Apart from that free glass, which impressed many American patrons who were unfamiliar with wine and considered it exotic, the bar was a money maker. Maria called it “a gold mine.” A Manhattan cocktail — with cherry — cost 3 cents but sold for 15 cents, she explained.

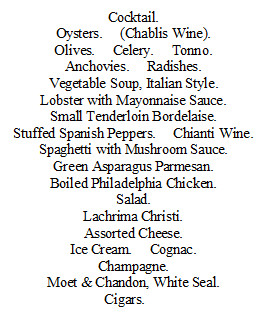

Banquet menus were grander and supplied more alcoholic beverages, as is shown in a 1904 menu above for a dinner given to honor a supporter of Democrats in the Tammany-controlled area occupied by the restaurant.

The restaurant’s best years were before World War I, when it was not unusual to serve four to five thousand dinners on an average weekday and double that on a good Saturday or Sunday, with waiting patrons spilling down the hall and into Macdougal Street. When food ran low the cooks would water the soup and waiters would offer patrons omelets.

With the onset of Prohibition, Maria’s father decided to get out of the business and concentrate on his other interest, real estate. Under new ownership, Gonfarone’s remained open for another 10 years, until 1930. The buildings were razed in 1937.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

Just like certain dishes are enhanced with a wine pairing, I find that my enjoyment of certain articles (like this one) is likewise enhanced. In this case, with a nice antipasto and a glass of Moet 😉

Thanks Jan!

Cheers!

Dear Jan, I am so thrilled and lucky to have found your wonderful and amazing article/story/history about Maria Sermolina! I grew up on the same street in Westport CT where Maria used to spend her Summers (that is what I have been told). My family and I were just reminiscing about our neighborhood and the neighbors which all seemed so interesting to me. We had artists, writers,cartoonists , actors etc. Right around the holidays, this past year, we were discussing the neighbors and we all wondered about Maria and her background. I was in my teens when I knew her so didn’t think too much about asking people about their lives back then. She lived next door to my great grandparents home (Also Italian and similar ages as Maria). We all heard stories about a connection to Benito Mussolini. She also had a housekeeper who was rumored to have dated Mussolini so when I read your article – It confirmed the stories we had been told! So interesting and exciting! It has sparked my curiosity so now I’m on a mission to find her book !

Thank you again!

Sandra Calise Cenatiempo

Thank you, sounds liked you lived in a great neighborhood. The book is good!

Interesting. I see she is listed.

Hi Jan — What a fascinating time trip back to old New York! It is fortuitous that Maria Sermolino captured the restaurant in her book. There must have been so many similar restaurants in NYC that were popular at the time but are now completely forgotten. Thank you for this very interesting article! Regards Bob

Sent from the all new AOL app for iOS

How interesting – an atypical career, or so I would have thought but who knows – for a restaurateur’s daughter, at the time.

I wonder what boiled Philadelphia chicken was. A quick search pulled up nothing obvious.

No wonder, with that level of sales weekly, the father didn’t tarry much over pilferage. Gold mine days for hospitality.

Gary Gillman

I think her career was definitely atypical.

All the graphics in The Quill are priceless!

Yes!