Lately I’ve been browsing through The Ford Treasury of Favorite Recipes from Famous Eating Places published in 1950. [illustration from Ford Treasury]

Among the 245 restaurants featured in the book, one stood out. Only Fanny’s gave no recipe. Instead, the ingredients of its salad dressing were simply listed. They were oil, tarragon vinegar, chutney, brown sugar, salt & pepper, mustard, fresh tomatoes, tomato paste, orange juice, ground pecans, garlic, onions, celery, and parsley.

The reason given was that the recipe was a valuable asset for which the owner Fanny Lazzar had been offered as much as $10,000. It was a “secret” recipe which, along with the restaurant’s spaghetti sauce, was closely guarded. The trademark had been registered in 1946.

Through the years the amounts said to be offered for the recipe increased mightily. In 1958 it was up to $250,000 according to the book Who’s Who — Dining and Lodging. (Oh, and it just happened that Fanny Lazzar was on the Advisory Board of Directors of the Who’s Who Historical Society that published the book.)

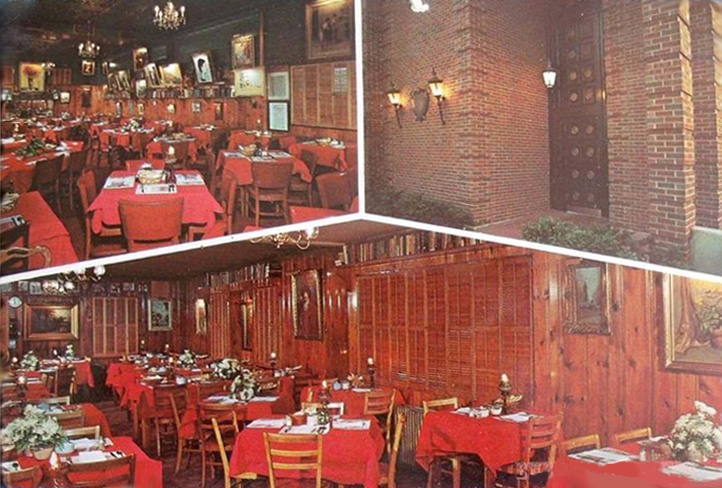

The more I learned about Fanny Lazzar and her restaurant, the more I began to realize how much effort she put into promotion. She admitted that she needed to have a full house regularly since she had no bar. Evanston was a dry town until 1972, although patrons brought alcohol to Fanny’s with no fear of a police raid. [Note wine glasses on the table in the illustration]

Fanny had started the restaurant in an industrial area in Evanston, Illinois, in 1946. She was a divorced mother of two boys facing the challenge of creating an upscale restaurant in a downscale neighborhood. She approached the local newspaper, the Evanston Review, asking if she could start a weekly column. She was told that restaurateurs did not have columns, so she bought a want ad instead. Almost accidentally, that provided a tremendous boost to her business.

Her Evanston Review advertisement was sent on to The New Yorker magazine by a professor at Northwestern University. The magazine included the entire, lengthy classified ad under the heading “Anticlimax Department (Fried Chicken and Violets Division).” It began with a quotation from John Milton (“‘They eat, they drink and in communion sweet, Quaff sweet immortality and joy”) and then told a story about visiting her uncle and aunt in Italy when she was 6. She spent time lying in the grass and smelling violets. Her aunt called her in to eat, and insisted that she do so even though she said she wasn’t hungry. Her uncle intervened and said she could go back and enjoy the violets. Next her classified ad launched into promoting dinner at her restaurant, suggesting that her “fine spaghetti” with its “rich meat and all butter sauce” would restore “SOMETHING that seemed lost.” Then it gave the restaurant’s hours on Sundays and the prices per various pieces of chicken, for example one chicken leg, 75c.

Marshall Field III, grandson of the department store’s founder, saw the New Yorker’s teasing putdown (did he recognize it as such?) and decided to give the restaurant a try. After his visit he introduced wealthy friends to it, including J. L. Kraft, Oscar Mayer, Richard Sears, and the presidents of Montgomery Ward and the First National Bank of Chicago. Fanny’s was well on its way to becoming a society restaurant. Although her first year in business had ended in the red, she was beginning to build a following.

Over the 40 years she ran the restaurant, Fanny invested in many, many advertisements, as well as producing 40 years worth of weekly promotional columns in the Evanston Review and the Chicago Tribune. Her paid advertisements appeared monthly for years in the Rotarian magazine. Despite being on the so-called wrong side of the tracks, Fanny’s location was not entirely a bad one. The Rotarian’s headquarters were only six blocks from the restaurant and it was close to Northwestern University and not so far from Ravinia’s summer music festivals. [above, an enlarged view of the restaurant, possibly in the 1960s]

She endlessly boosted the restaurant, repeating over and over that it had been honored by foreign governments and the Butter Institute of America, visited by famous celebrities, and written about in more than 165 newspapers and magazines. In her first column in the Tribune in 1955, she reiterated her triumphant claims: written up in 15 national magazines in the first two years; recommended by three of Europe’s finest restaurants in her fifth year, including the Tour d’Argent in Paris; and that she personally still prepared a garlic bread so fine that nobody had ever succeeded in copying it.

It’s likely that all her patrons and many others in the Chicago area, the country, maybe even the world knew Fanny’s saga: spending the first year serving industrial workers in the neighborhood, shoveling her own coal, and sleeping fewer than four hours a night. How she spent a full year each developing her salad dressing and her spaghetti sauce. And how she hired chef Bobby Jordan to fry chicken after he told her he had been “sent by the Lord.” And how she met her second husband, Ray Lazzar, while dining at the Pump Room where he was captain of the waitstaff.

Her success enabled her to live well and to become a local philanthropist. But she seemed to reveal her continuing insecurity after a student at Northwestern University gave the restaurant a poor review in the student newspaper in 1980. He wrote that Fanny’s was “overrated,” decorated to “look like it’s a rich man’s garage sale,” and that the spaghetti sauce was “just a tinge above Ragu,” while the salad dressing tasted “just above vinegar and oil with food coloring in it.” [above: a latter day match cover]

She responded by taking out a full-page ad in the student paper in which she reiterated her success, even going so far as to list in capital letters two columns with names of “GREATS” who had patronized her restaurant. She called her critic a “gross ignoramus” and concluded the long letter saying, “your bungling efforts at reporting a WORLD FAMOUS RESTAURANT WERE NOT ONLY WITHOUT TRUTH, BUT ODIOUS AND ABSURD.”

Two years later the school’s new restaurant columnist decided to give the restaurant another test. He was in agreement with the 1980 review and complained about soggy iceberg lettuce, greasy “orange-flavored” salad dressing and chicken that wasn’t “nearly as crisp as the Colonel’s.”

It’s hard to know if the restaurant had declined or if the student critics were poor judges of quality.

Ray Lazzar died in 1984, which was surely a blow, and the restaurant closed as of the end of July in 1987 at which time Fanny was 81 years old.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.