Almost as soon as the Chinese began arriving in San Francisco in the 1850s their restaurant dishes became news of interest. A story appeared in major dailies in 1849 which observed that there were “two restaurants in the town, kept by Kong-sung and Whang-tong, where very palatable chow-chow, curry and tarts are served up by the Celestials.” [Above: early 20th century, San Francisco, when the dining area was usually on an upper floor; Below: elaborate interior of a San Francisco restaurant]

From the start, as this quotation reveals, there was a lot of guesswork in the identification of many of the unfamiliar dishes prepared by the newcomers. The same often applied to proper names.

But the level of interest was high, despite the fact that the Chinese themselves did not experience widespread acceptance, quite the opposite in fact. So the above 1849 report by poet, diplomat, and world traveler Bayard Taylor, which showed appreciative curiosity, stood in stark contrast to the many ugly slurs against the Chinese that would appear through the decades.

Despite the mixed attitudes toward Chinese immigration, their restaurants were popular with a wide range of patrons in early San Francisco. The most elaborate of them sometimes furnished formal banquets for visiting American dignitaries that featured exotic delicacies such as bird’s nest soup.

Although many Chinese kept their traditional grooming and clothing, they proved to be very adaptable in catering to America’s tastes and needs. Gradually moving from San Francisco to the western territory, they opened small eating places, sometimes in the back room of a saloon.

They quickly learned what their customers liked. A man named S. Ling Ning, who ran a restaurant in a mining area of Arizona, demonstrated adaptability in producing baked products, according to his 1873 advertisement.

Hateful sentiment toward Chinese had grown intense in the 1860s and 1870s, as is evidenced in a memoir by a woman who had moved to the silver mining boomtown of Virginia City, Nevada. She denounced the Chinese in the ugliest terms, calling them a “thieving, murderous, licentious, filthy, pestilential race of heathens” who should be banished from the land.

There is something ironic, if that is the right word, about ‘white’ Americans eating meals cooked by people they despised.

In 1882 the Chinese Exclusion Act prohibited the Chinese from immigrating or becoming citizens. The act was not reversed until 1943. Many left the U.S. because of the act, while others began to migrate in an eastern direction due to the level of hostility in the West where “No Chinese” was becoming common in want ads for restaurant help.

Despite the eastward migration, by 1885 there were said to be only six Chinese restaurants in New York City’s Chinese settlement area, according to a report by journalist Wong Chin Foo. Most New Yorkers were leery of patronizing them, he wrote. One of the six he described as grand, attracting “Hong Kong merchants, Mongolian visitors from ‘Frisco, and flush gamblers and wealthy laundrymen.” In other words, most customers were then limited to the Chinese. But it did not take long for the non-Chinese population of the city to “discover” Chinese restaurants. [Above: early 20th century, NYC]

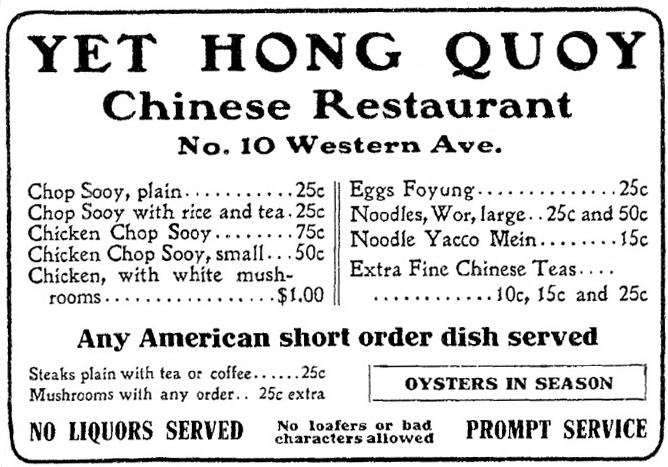

Chinese cooks continued to be highly adaptable to American tastes. Along with learning to turn out favorite American dishes such as stew, steak, and potatoes. [Above, Muskegon MI, 1906]

And there were some Chinese chefs who mastered cooking French dishes after training by French chefs. In his 1906 book A Requiem of Old San Francisco, Will Irwin notes that “most of the French chefs at the biggest restaurants were born in Canton, China.”

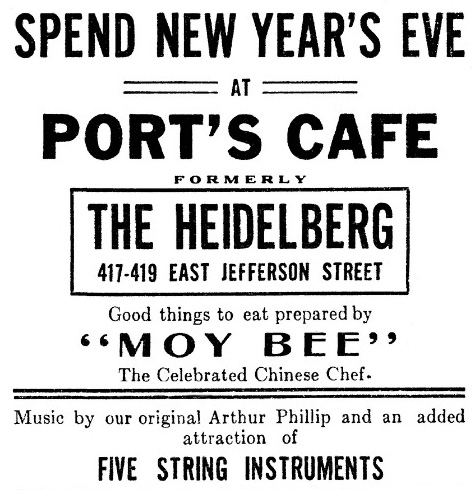

Chinese chefs also learned to prepare German dishes. James Beard and his mother were patrons of two Portland OR German restaurants, House’s and Huber’s, both of which were staffed by Chinese cooks. The venerable Huber’s was known for its turkey and cole slaw. Beard’s family meals were also prepared by a Chinese cook. [Above, Springfield IL, 1915]

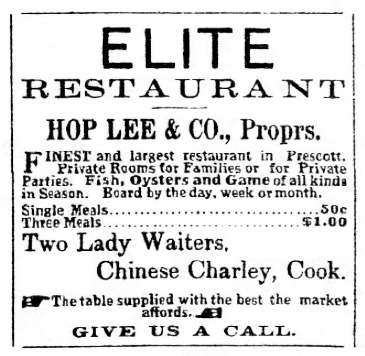

Chinese food, even when adapted to American tastes, did not qualify as a basic American “square meal” but it caught on with Americans anyway. In New York City, according to reports, among the non-Chinese population it was free-wheeling bohemians who were first to discover and enjoy Chinese restaurants. According to one observer, they were said to like the low prices that allowed them to escape from “the insipidity of cheap chop houses and the sameness of the dairy lunch counters.” [Elite Restaurant, Prescott AZ. 1892]

By 1903, according to the New York Times, there were “an estimated 100 chop suey places between 45th street and 14th and between the Bowery to 8th Ave.” However, the story continued, they were mainly patronized by Western visitors since many New Yorkers did not like Chinese servers. Chinese restaurants outside New York’s Chinatown were reportedly popular with Black Americans who hesitated to go into Chinatown but felt comfortable when many of those restaurants began to relocate.

As is well known, the number of Chinese restaurants increased throughout the 20th century, eventually outnumbering McDonald’s. [Above, Chicago, 1913]

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

Home Dairy was a late-19th/early 20th century chop suey restaurant in Georgetown, Colorado owned and operated by a Chinese-American man cook, restaurateur, and politician.

I found this article to be very interesting. Thank you for your research!